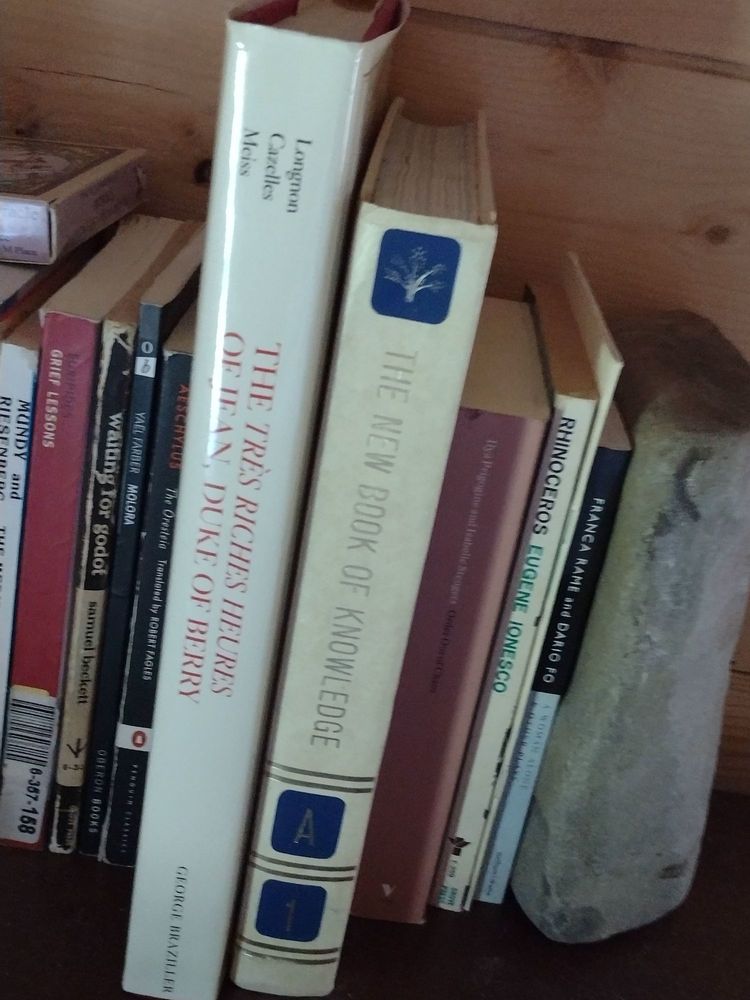

A few years ago, clearing out her bookshelves, my mother packed into boxes a complete set of The New Book of Knowledge she’d purchased in the late 1980s. She saved only the first volume, a book that now has pride of place in my own library. It serves as a tribute, I guess, to my child-self and the zeal and determination with which I made an earnest attempt to read through the entire collection, starting from the letter A. I moved, I remember, fairly rapidly through the volume’s initial, shorter entries, including “Abacus,” “Abbreviations” and “Acid Rain.” “Africa,” though, even reduced to twenty-two pages, suggested a whole continent of information I knew I couldn’t possibly absorb. I filed the book back on the shelf, forced to admit the utter impossibility of my task. And yet even now, just a glance at that volume sends me back with a little ripple of pleasure to a time in my life—a time before the internet—when it was still possible for a young person to gaze at 26 volumes on a shelf and imagine absorbing a whole world of knowledge by conscientiously setting out to read from A-Z.

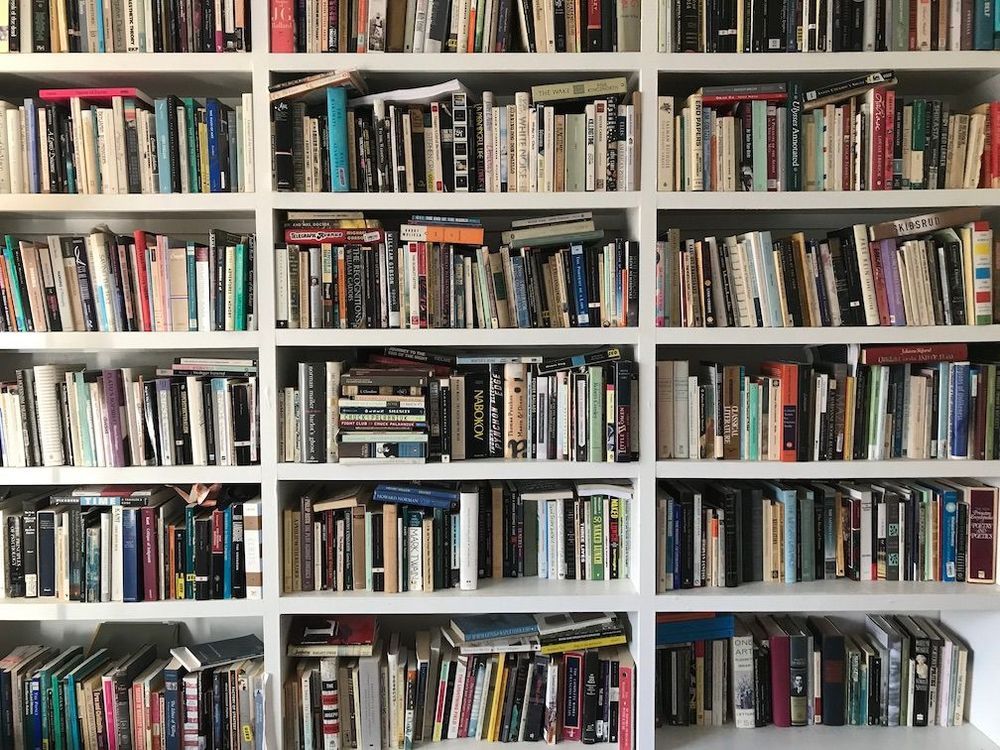

I think of Jorge Luis Borges’s “Library of Babel”: “The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries.” My own library is now divided between the two places I call home: Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and Tucson, Arizona. The “summer collection”—kept in Cape Breton—is made up mostly of kid’s books, many from my own childhood. There’s also a lot of nature books, books I absorbed over the years from my mother’s collection, a complete set of Dickens I inherited from my father, and a whole bunch of doubles (books my husband also had copies of and so were left behind when we moved to Tucson together back in 2011). “Doubles” in fact make up a significant percentage of the library—a good sign of compatibility, I guess. But where my copies (the ones left behind, which make up the “summer collection”) are riddled with asterisks in the margins and frantic, scrawled notes—my husband’s (in the Tucson collection) are not. This is an important difference—and one we came by honestly. My mother, an educator and former English major, saved almost everything from her college reading lists. Growing up, I remember I always had a special affection, and possibly a more particular affinity, for those books I inherited from her. I loved lifting the cover and seeing her name—and sometimes the name of her college dormitory—written neatly on the first page. I loved seeing the traces of her reading and thinking written, sometimes quite literally, between the lines.

By contrast, my husband cringes when he sees me marking up a book. Any book—even those that are officially “mine.” For him, books are not only a means of transmitting experience and knowledge, a record and potential palimpsest of different trajectories and engagements with thought; they are also discrete objects attached to particular histories and values. His father (also an educator and former English major) is now a serious book collector. His extensive library boasts an impressive collection including a complete set of Henry James first editions and personal letters from Susan Sontag, Harold Bloom, and William Faulkner. When he lifts a signed first edition off the shelf or draws our attention to a particular word written in a particular scrawl by a particular hand, I get it—I really do. I feel a rush of recognition and contact not only with the words, or the ideas behind the words, but with all the time and effort and material and desire that went into those words appearing in just that way: in that particular book, or behind that particular sheet of glass.

Years ago, in a narrowly avoided house fire, I lost a couple of my grandmother’s handstitched crazy-quilts. “It doesn’t matter,” I remember saying hastily when I realized what had happened. “They’re only things.” I said it because I knew it was what I was supposed to say in a moment like that—and also because it was true. The knowledge that I could easily have lost more felt close, and real. And yet, as I said the words out loud, I realized with a sick sort of jolt that they were also a total lie. My grandmother’s quilts weren’t, and had never been, just things. They were always, instead, a literal patchwork of different moments of experience and time. A record of human effort and love—a living testament to the persistent desire to preserve and cherish the present for the sake of the future. A touchpoint to a mostly unknown or already forgotten past.

Around the same time of the narrowly averted house fire when I lost my grandmother’s crazy-quilts, my first book of poetry was published by a small letterpress publisher famous for the tremendous care and attention to detail that goes into their design. I was immediately enamored both by the simple beauty of the books and the practical philosophy that simple beauty conveyed. A book’s beauty comes from the fact that it’s essentially utilitarian, I remember the publisher told me at the time. A book is an object, a tool—and so should be treated as such. I loved that this approach seemed to recognize the aesthetic value of a book’s object-ness while at the same time emphasizing that a book’s job was ultimately to transcend, or render irrelevant, its fixed, and apparently singular form.

But after the unexpected success of my first novel, published by the same small press, the tension between these two impulses (on the one hand, toward crafting and cherishing a book as a precious object and, on the other, toward recognizing it as a simple tool) felt especially acute. My publisher’s initial reticence to sell book rights to another, more commercial publisher, who could easily meet the sudden demand, sparked a heated debate within the Canadian publishing world over the relative value of content and form. The old adage, “You can’t judge a book by its cover,” seemed at least momentarily forgotten by those who championed the small press’s aesthetic and/or anti-corporate resistance to literary prize culture and shifting capitalist demands. Bewildered, I wondered where the utilitarian aspect of the small press philosophy had suddenly gone—or how the fetishization of any commercially-produced object (even a literary one) worked to undermine capitalist mechanizations of desire. Big publisher or small publisher, it all seemed just about the same to me when what I wanted—despite or perhaps because of the sudden attention to my deeply personal first novel—was genuine contact with and through the book’s content. I wanted someone to say (and on very special and rare occasions I was overjoyed when in one way or the other they did), “I just loved sensing the barely-transmittable experiences you were trying to convey…”

It’s a funny, vertiginous feeling to stand in front of one’s own bookshelf and imagine each book as a sort of porthole opening, potentially, onto a nearly infinite network of other barely-transmittable experiences; to imagine all the ideas and emotions, not-quite-fully-expressed; the missed allusions, the various ways juxtapositions and metaphors might otherwise function, for myself at different moments, or for a different person at a different time. Funny. Dizzying—and strange. To think of all the crossed-out words and paragraphs, whole chapters or sections either deleted or completely revised… As well as—of course—all the books that didn’t get written, because of the one that eventually did.

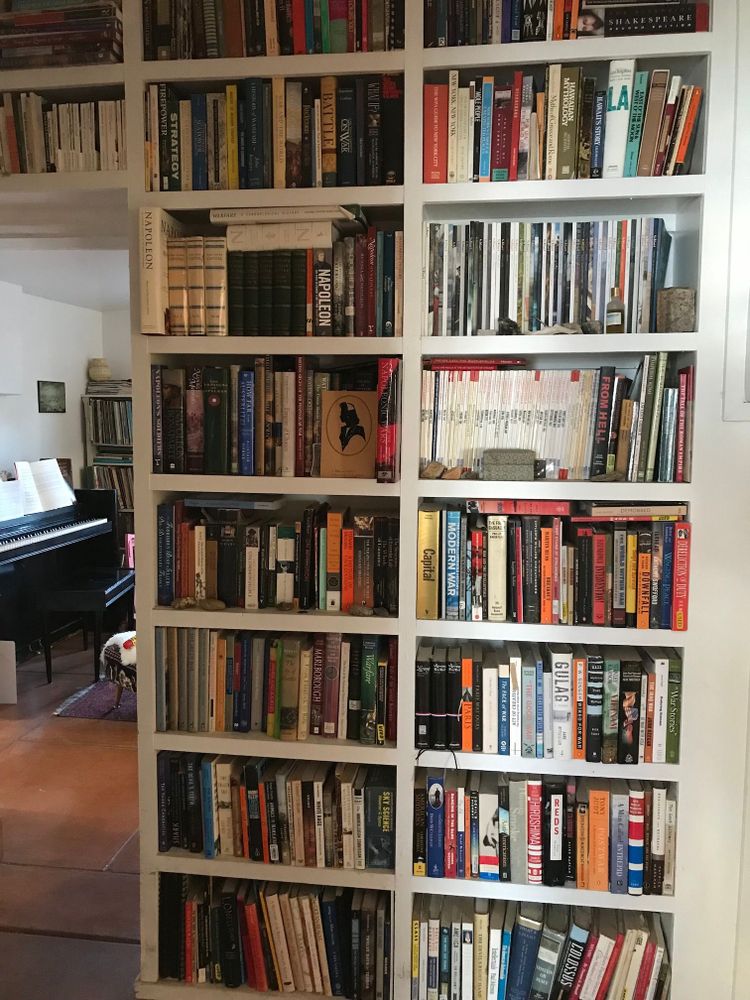

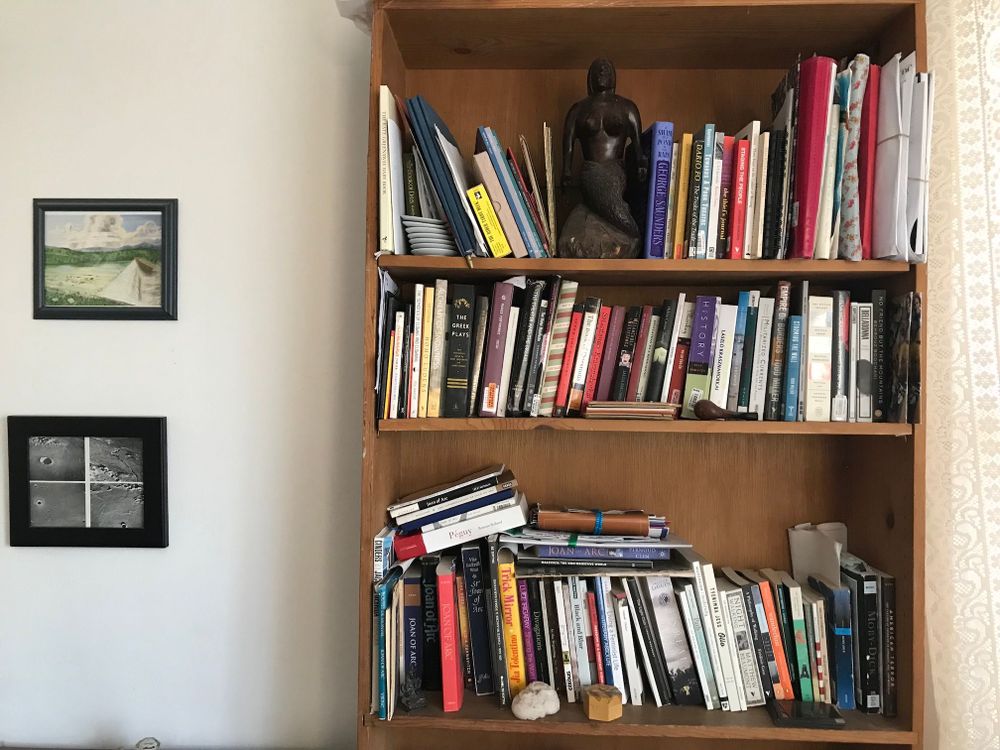

It’s thanks to the curatorial efforts of my husband that our Tucson library has been organized by genre and theme. There’s a special section for poetry, one for plays, and (thanks to my father-in-law) a small collection of rare books and first editions. There’s a wall of Canadian fiction, another of philosophy. The hallway has become a sort of tunnel through some of the worst moments in American history. Probably my favourite part of the collection, though, is made up of books that I haven’t read. I keep a disorganized assortment of them within easy reach of my desk—books of every genre, which have either been passed on to me or, for one reason or another, have caught my eye. I hope I’ll get the chance, eventually, to read every single one—but in the meantime I love simply having them nearby. I love sensing—through their simple presence, their physical form—all those countless new directions, and possible meanings. All that intention and desire; all those layers of effort, and time.

In “The Library of Babel,” Borges notes a mirror in the library vestibule that reflects a single wall of books, causing it to appear twice: once in reality, and once as a mirror-image of itself. “Men often infer from this mirror,” Borges writes, “that the Library is not infinite—if it were, what need would there be for that illusory replication? I prefer to dream that burnished surfaces are a figuration and promise of the infinite…” Likewise, the books that I haven’t read (as well as the ones that I have and would love to read again, always somewhat differently), are both a challenge and a comfort to me. They represent the infinite possibility contained not only within my personal library, but within every moment of human experience, and the various forms of expression that experience takes—or might begin to.

With their uncracked spines, they also represent the uncertain, but nevertheless sincere promise implicit within the material of language (and therefore also of books, and libraries) brilliantly explored by Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s “Future Library” project. In 2014, Paterson launched her project by planting 1000 Norwegian Spruce Trees somewhere north of Oslo. By 2114 she will have both commissioned the work of 100 different authors (one author a year for the duration of the project’s proposed 100-year timeline) and generated the material to publish each work in a future where paper books may well be nearly obsolete. Like many of Paterson’s projects that confront the relationship between vastly different (human and non-human) timescales, “The Future Library” challenges us to think about the reciprocal relationship we often take for granted between culture and the material resources that underpin every technology we devise to transmit that culture. We can’t entirely separate—Paterson’s project suggests—subject from object or content from form. Just as we can’t disentangle the future from the past or our (ultimately finite, dependent) selves from the earth and its resources.

Last night I had a dream that my father, who’s been dead for over ten years, was still alive. I was overwhelmed in the dream by a sense of shame, and of loss. How could I have not known, or somehow “forgotten” that my own father was still alive—living by himself in a small, untidy room somewhere in the Midwest? How had I not visited him in all that time? Somehow, in the dream, I managed to reach him. The room he was living in had low slanted ceilings and was mostly bare except for a bed and a small shelf supporting a couple of photograph albums and a stack of books. The two photo albums were propped up next to on another: one was filled with photographs of my own recent life and the other with photographs of my sister and her family. There were wedding photos, I remember, and a lot of pictures of grandkids he’d never met. The way the albums were propped up they seemed almost like living avatars, a way for my dead father to enter and keep up with our lives—even across the disconnect and distance that somehow had been introduced. My attention in the dream then turned to the stacked-up books, which on closer inspection I noticed were all poetry anthologies. Each one was studded with bookmarks, so I knew that my father had been actively reading—interested (just as he had been in life) in keeping up with anything that was of special interest to me. “What are you reading?” he used to ask every time we talked on the phone. Often, the next time we spoke, I’d learn he’d driven to Sam’s Club or his local library to pick up a copy of whatever book I’d mentioned. In my dream, I stood in front of my father’s bookshelf and felt—as well as a wave of regret for the impossible distance that separated us; a breach in space and time I could in no way overcome—a sense of comfort and relief. I knew that, despite distance, and seeming impossibility, my father was still out there, still borrowing from the library, still devotedly reading. Still hoping—in whatever way—to make a connection.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Skibsrud, Johanna. “Johanna Skibsrud: Shelf Portrait.” Shelf Portraits, 2 December, 2022, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/johanna-skibsrud-shelf-portrait. Accessed 20 February, 2026.

APA

Skibsrud, Johanna. (2022, December 2). Johanna Skibsrud: Shelf Portrait. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/johanna-skibsrud-shelf-portrait

Chicago

Skibsrud, J. “Johanna Skibsrud: Shelf Portrait.” Shelf Portraits, 2 December, 2022, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/johanna-skibsrud-shelf-portrait.

Johanna Skibsrud

Johanna Skibsrud is the Scotiabank Giller Prize-winning author of numerous works of fiction, poetry and non-fiction, including The Poetic Imperative: A Speculative Aesthetics (McGill Queens 2020), Island: A Novel (Hamish Hamilton Canada 2019), and “The nothing that is”: Essays on Art, Literature, and Being (Book*hug 2019). A new collection of essays, Fool, is forthcoming from Routledge’s New Literary Theory series in 2023.