The oldest book I own is a precariously held together hardback of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Its gold embossed lettering on a navy blue cover opens to nearly translucent pages, and my dad’s name is carefully inscribed in cursive on the inside liner. When I was a child, I thought it was a Bible, even bigger and older than the one my dad secreted away in his bedside table. Over the years, it’s become spine-frail and coffee-stained, moving with me from my first student apartment to my first broke-artist apartment, to here, my first home with a real space I can call my own. When we were little, my sisters and I pressed flowers between its pages. Now, it holds a dried bloom from each of the first four bouquets I received from the man I would come to marry. I don’t know why, but I have always pressed flowers into the pages of my oldest books.

To be honest, I’m not a romantic, not really. But I am a recorder of family stories, and many of the books in my library are just that—marks of our past and records of the people we were when we read them. In their special way, like photographs (which are too going their way into obscurity), physical books are a link to more than just the stories written in them. They hold the smell and feeling of when they were given, when they were read, and who and where we were when we encountered them. What else in this world can do that?

I should say that I do not hold every book in my collection to this esteem. I am not a hoarder of books, or especially attached to most of what is housed on my shelves. For the most part, books are a moment in time and I happily pass them along without a thought of them returning. If I lend out a copy of a book that I later want to read again, I simply buy a new copy. I feel like the more books there are circulating in the world, the better the world is.

I believe in stories, above all else. Sharing my collection with others is almost as good as building a library for myself. This is something that runs deep in my life. My mother, father, and stepmother have all had impressive libraries and have always given freely their collections. As children, we were encouraged to read any book that caught our eye on the shelf-lined walls of their homes. Unlike television, movies, and music, which were regulated stiffly, we were given unfettered access to every book no matter the content.

I’m an adult now, a married mother of a baby girl who I hope will grow up to be a reader like I was. Like my parents, I plan to give her unrestricted access to whatever she chooses to read. Like me, I hope she reads beyond her understanding at a young age, and that reading opens up a dialogue which informs her thinking as she grows. I did not understand The Iliad when I read it at 10 years old. But I knew it was beautiful, on the page and in my mind. I loved the tight columnic verses, the end rhymes. I had no idea what I was reading, but I read it just the same, lying on my belly on the floor of our spare room, which doubled as the family’s reading room.

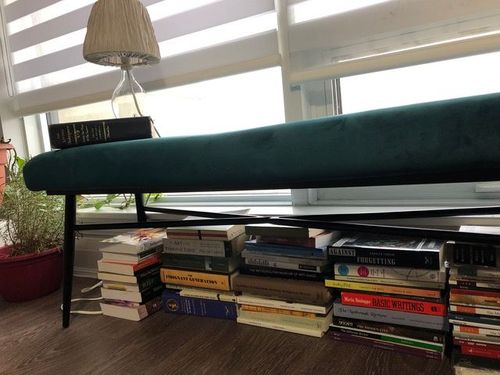

These days, my books are housed in custom-built glass cases that my father in law built and suspended from the second floor ceiling. In an effort to save space and my ailing back, I have graduated over time from the weighty hardbacks I loved so much as a child to mainly soft covers, jammed in haphazardly, accessible only by a small stool. When trying to locate a particular title, I must climb to the middle of the third floor staircase, as my height makes it impossible to know where to begin from the floor. I have dreams of one of those lovely moving ladders that libraries in the movies always have. I would climb up, whipping from side to side to find just the right book, perhaps singing with one arm extended like Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. Alas, the tight space of a Toronto area townhome does not support this particular fantasy. But, maybe someday.

These built-especially-for-me shelves have a wide variety of books on them. Some are older than I am, having been passed along from my father over time, and some are so new that the spines are still pristine.

My copy of Lord of the Flies is one of many books of my father’s, acquired in ninth grade English at Queen’s Royal College in Trinidad. I insisted on using this version in my own ninth grade class only to find myself constantly lost, as the page numbering has varied over the years. This book has the best of treasures that books can give—notes in the margin in a fine pencil, my father’s teenaged writing. Little messages from the man who graduated from this elite school despite the poverty of his childhood and became a physician. Remnants of a boy who worked and studied hard, considered literature and sought academic perfection from an early age. A tough act to follow, for sure.

As I said, I do not hoard my books but the books that I love, I own several copies of. In fact, I count at least three versions of Wuthering Heights. They are all Penguin Classics paperbacks, one special one has a note in it which my Grandmother wrote on one of the last visits before her death. It says, “Love Grandma Kane” in a cursive that is precious and familiar. My grandmother, Laurel, is one of many ghosts in this space. The oldest books have names and messages scrawled inside their covers, a long tradition in our family of never gifting a book without writing in it first.

By signing our books we pass along a message of the moment we realized the story we held could mean something in the life of someone else. Books continue to be my favourite greeting cards and the best gift to receive.

My favourite library guru is my stepmother, Mavis. Ever stylish and strongly opinionated, this woman knows her way around a perfect reading room. She has the most extensive and varied book collection of anyone I know, and she picks the best books as gifts. It is thanks to her that my own library has a complete, hardback copy of the Oxford English Dictionary and Thesaurus, and a current world atlas, despite our living in the time of smartphones and Google. There’s something about a hardcover dictionary, isn’t there? So much better than scrolling the internet for the perfect word.

Mavis is also a fearsome feminist who found her place among Berkley feminists in the 1960s. To my collection she contributed The Communist Manifesto when I was 16 years old, as well as work by V.S. Naipaul, Alice Munro, and her favourite, Sylvia Plath. Mavis has stocked my collection with work of importance from the very beginning, pressing feminist and socialist literature as well as stunning works of fiction and poetry by writers of colour and women writers into my impressionable palms from my early reading days until now.

Each visit home brings another interesting addition—books about the Canadian prairie, Post-Colonial Trinidad and Tobago (The Woman on the Green Bicycle), and first and foremost the stories of women in this country and beyond. Above no one else, it was she who first taught me that women had important stories to tell, and that stories were bigger than what I could drum up from my first vantage point in Saskatoon.

Although my mother and father were the first to provide me with a curiosity for reading and the pure pleasure and escapism that reading provides, Mavis showed me that artists are important and that the work of writers can change the world.

This is what I hope my daughter will come to understand as well. I will start her reading education with The Inconvenient Indian, by Thomas King, which I own in hardcopy and paperback. When she is older, she will have access to work by Sherman Alexie, Richard Wagamese, Langston Hughes, Maya Angelou, Gregory Scofied, Louise Bernice Halfe. She will never have to look far to find the stories of her country, and the world she was born into. She will never have to wonder if Indigenous, Trans, Caribbean, Gay, Female or any marginalized person who looks or thinks like her, has a story to tell or the means to tell it. I will surround her with voices which help her understand that her own voice is valid and important.

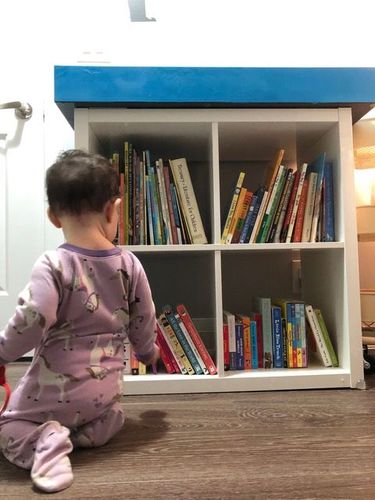

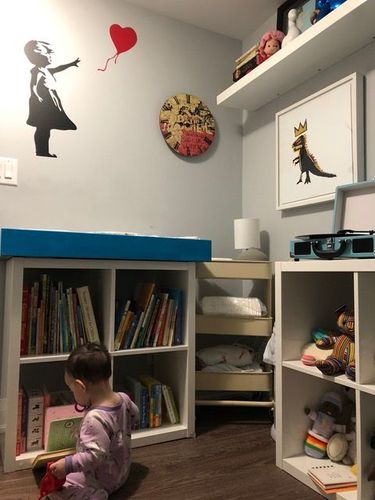

Even before she was born, I advocated for her reading education, resisting the tradition of baby-showers where women sit around cooing over pink ruffled baby clothes and men get the day off from the social responsibilities of their wives. I decided that a “book shower” was what we all needed to celebrate the arrival of a new baby girl. I challenged my friends and family members to find children’s books featuring female characters who solve problems and overcome obstacles without the aid of male support. I asked for books depicting “alternative” families, and books focusing on mythologies outside of the Western colonial perspective. My friends and family members did not disappoint. Her shelves are now brimming with baby books in French, Cree, and English. She learns the Coast Salish and Haida artwork for the animals of the West Coast, reads Feminist Baby and What Does a Family Look Like?

When she is a little bigger, she’ll discover as well Madeline and Roald Dahl and all the classics I devoured as a girl. Her library has books from my childhood, dog-eared and over-read. Alligator Pie, The Giving Tree, The Dreamkeeper, Jonathan Livingston Seagull (also a Mavis addition), a scattering of hardback Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew novels from the 1970s (whose content and language will hopefully spark conversation when she is old enough to question roles of race, class, and gender), and all of E.B. White’s charming stories.

On a separate shelf, there is an hardback children’s glossy of Uncle Remus’ Stories which I keep as a mark of the times, a children’s book from my own childhood library which is littered with racially offensive language including a casual use of the n-word. This is a book I keep as a reminder for my children of just how slowly the world changes and how normalized oppression can become. This is a book we may never read together but if she wishes some day, I hope it sparks a conversation in her and helps to understand the importance of record keeping and storytelling, and what happens when only one group of powerful people are given the ability to speak and record their stories.

As I’m sitting here looking at all the years of books, the piles of slim Canadian poetry by Lorna Crozier and Tim Lilburn, Dionne Brand, Laurie D. Graham, Arleen Pare, and stunning debuts by Canisia Lubrin and Caroline Szpak. The hint of my husband’s influences is there: books on the history of the Las Vegas Strip and magazines about concrete. A paperback version of The Picture Bible; its graphic illustrations are a remnant of my pre-lapse Catholicism and a nostalgic nod to all the hours of Church time which continue to influence my work and my interactions.

The books I have held onto all these years, moving from place to place as my life expanded and contracted, and others I have long discarded packing up box after heavy box, leaving piles to charity and in compact boxes beside the dumpsters. There are books I have read over and over – To Kill A Mockingbird and The Outsiders. And books I have yet to read. Some I may never open. Most of these books house the messages of both the living and the long dead. They are the voices of the characters but also the whispers of my own complex history, and the record of my life that my daughter will some day discover. My library is the place I go to for silence and concentration, amid the constant murmur of the voices of the past.

Writing this, I pull out a hardcover that my father gave to me in the third grade, A Treasure of Literature for Children. I remember so clearly receiving this book, heavy and filled with so many stories it felt impossible to read them all. The book came from Halifax, where my father and stepmother were living at the time, and included favourite works by A.A. Milne (his poetry, not the expected Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too) and a complete Aesop’s Fables. This particular book has been so read that the spine is wobbly and there are stains all over the pages. Like my Shakespeare, it is precarious to open, terrifying even, and the inside cover has a note in my Dad’s very distinct writing; “Cara-Lyn: Please read these good old stories and remember Christmas, 1987 and your Dad.” I wonder if I should write my daughter a note too, now that it belongs to her. The pages fall open to Pinocchio, where I find a thin tissue package, and within this, a single dried red rose with no note, years old and long forgotten. This book, this space, is the altar of my past, and I am most at home here, within it.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Morgan, Cara-Lyn. “Altar of the Past.” Shelf Portraits, 25 June, 2021, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/altar-of-the-past. Accessed 20 July, 2025.

APA

Morgan, Cara-Lyn. (2021, June 25). Altar of the Past. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/altar-of-the-past

Chicago

Morgan, C. “Altar of the Past.” Shelf Portraits, 25 June, 2021, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/altar-of-the-past.

Cara-Lyn Morgan

Cara-Lyn Morgan comes from both Indigenous (Métis) and Immigrant (Trinidadian) roots in the place known as Turtle Island and Canada. She was born in Wascana, known now as Regina, Saskatchewan, and lives, works, and gardens, in the traditional territories of Anishinaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Huron-Wendat, and Mississaugas of the Credit peoples. She is ever grateful to these original caretakers of the land for welcoming her ancestral stories into this space.