For as long as I can remember, the spare room on the ground floor of my childhood home in North Central Regina has been designated a library. I have memories vivid of sawdust, carpenter nails, and the squeal of a saw as my father cut the boards and assembled the shelves in the back room on the ground floor. The kids at school were suspicious—I was always coming to school with fantastic stories—did we really have a pet crow? (yes, for a while). Was it true I’d read all the Anne of Green Gables books on the shelf in the school library? Did I really have a library in my home?

As an adult interacting with other writers, I’ve since come to realize how rare it is to have parents who read, much less shelves filled with Leonard Cohen, Gwendolyn MacEwen, and Pat Lowther. I’m grateful for the presence of books and art in my life early on—even my father’s terrifying H.R. Giger books. I treasured atlases and books of castles alongside illustrated books of faeries and gnomes. When I was very young, I remember crying because my name wasn’t in the dictionary, and my younger brother Credence’s name was. It felt unfair that his name had a meaning outside of himself, and mine didn’t. My parents tried to reassure me and finally, my dad got a volume of poetry down from the shelf, showing me Neal Cassady on the title page. My name was in a book (spelled differently—but that didn’t matter). I stopped crying. I felt seen.

My father never finished university, instead working as a surveyor up North, and then a facility operator at the local field house (he referred to himself a janitor), but I grew up with memories of him reading Gravity’s Rainbow and Infinite Jest. He spent evenings in the basement, where he worked on wood carvings, and later rock-climbed on a wall he built, pouring resin handholds into latex moulds. The basement was also where he kept his desk and typewriter and, when we were very young, my father would write his poems. My mother opted for reading Gone with the Wind or The Stand. She was the one who coaxed me to read the Anne books when I resisted the opening chapters. I went on to devour Emily of New Moon, and The Story Girl while she leafed through Stephen King books she picked up from the laundromat on camping trips. Every Christmas Eve, I would open a book from my Uncle Bill—often Jane Austen, or a collection of short stories, and when I started university, my mother and I read the assigned Alice Munro collections together. My three brothers have since become artists or writers. My dad still reads contemporary fiction. My mother died in 2020.

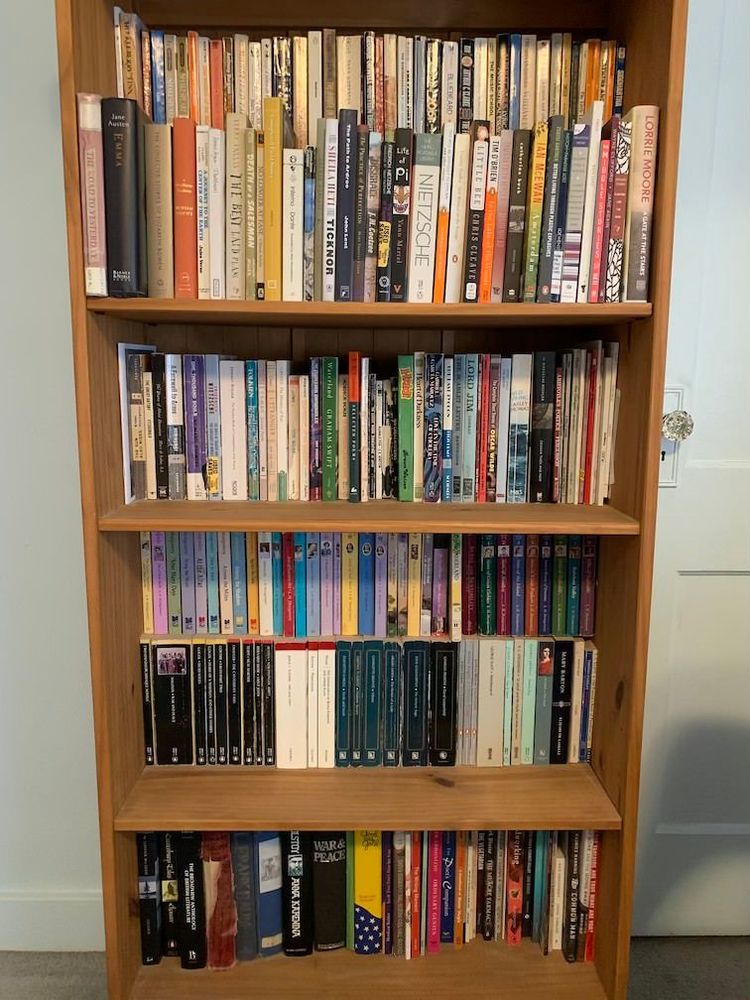

My own library is fractured, spread over the cities where I’ve lived. I still have books in my childhood bedroom— The Secret Garden and the Anne books, but also most of my university reading— books from the canon I desperately tried to catch up on upon entering university and feeling like everyone knew a language I couldn’t speak. I have translations of Dostoevsky and Camus from used bookstores in Regina and Penticton—where we spent summers when I was a teen. These line the shelves I’d get for birthday gifts alongside the poetry collections of Saskatchewan writers like Karen Solie, Michael Trussler and Dan Tysdal as well as those writers who’d visit Sage Hill Writing Experience, or Moose Jaw’s Festival of Words.

My first writing workshop was with Yann Martel. At that time I stuttered so badly that even stating my name or the school I attended caused frustration and shame. I still remember the prompt Yann gave us that day—the first line of L’Étranger translated into English. “Today mother died.” I don’t remember what I wrote. I remember asking Yann to sign my book afterwards and shaking badly. More important than the workshop was this feeling of meeting a real published writer, and allowing myself to believe that such a life might be possible for me. As Yann wrote the inscription—May you reach the coast of Mexico—a reference to Life of Pi —his partner Alice Kuipers looked over my response to the prompt, an unexpected act of kindness.

Soon after, I worked with Pam Bustin, the writer in residence at Scott Collegiate—the inner city school she’d also attended. I wrote a short story following my classmate’s suicide. We’d been in school photos together since kindergarten, and this loss was difficult to process, upending me for months. Pam acknowledged this darkness, and didn’t turn away. When my voice felt too shaky to read my story at the writer-in-residence closing reception, Pam read it for me. I would go on to lose other classmates—my grade school best friend Maria, the twins Clara and Araya who I shared hours of speech therapy with. I started reading E.E. Cummings, Bukowski, poems by Edgar Allen Poe. In these poems I found a flicker of darkness that reflected what I felt inside. They gave me the sense I was not alone. These books of adolescence, highschool and university are in my old bedroom in Regina.

Taking a creative writing class from Medrie Purdham at the University of Regina changed my life. Medrie’s class was my first time encountering fixed forms like the villanelle, pantoum, and sestina. From Medrie, I read P.K. Page’s glosas for the first time. I liked the structure of fixed forms, which scaffolding to my thoughts and feelings, which felt flimsy without form. Medrie encouraged us to play with puns, and double-meanings, to research the etymology of a word and use it in a poem, to lean into assonance, alliteration, and rhyme, elements that I discovered helped me to read my work aloud without stuttering. The more musicality in a poem, the easier it flowed out, language becoming more like a lullaby or spell. I remember one prompt where we wrote a poem about a headline, memory or piece of family lore, misremembered. Another encouraged us to include our own name in the poem, which felt risky and subversive, and a hearkening back to that childhood desire to see my name in print. Maybe I could write poetry too. After the course, seeing my interest in form, Medrie introduced me to old English riddles, which used Anglo Saxon alliterative verse, a form led by stressed syllables separated by a caesura running down the middle of each poem. I liked the playfulness of riddles, how they subverted expectations with sexual innuendos, mixing together the sacred and profane.

In this creative writing class, I met poet Nathan Mader, who read me Rilke’s Duino Elegies for the first time. Nathan was a roofer and carried a pocket Emily Dickinson, stained with tar from years of hot roofing in Victoria. He’d moved back to Regina to finish his English degree and he told me about Véhicule Press poets like Asa Boxer and Linda Besner. After Medrie’s class, we took a Paradise Lost lecture with our professor Jeanne Shami, the wife of Saskatchewan poet Ken Mitchell, and a founder of the Regina Cathedral Arts Fest. We read poets like William Blake, Sylvia Plath, and Elizabeth Bishop. Nathan’s poems featured a compressed musicality, and he spent hours refining each image until it was diamond-hard. He read his poems aloud until they sounded just right. Nathan is still one of the best poets I’ve met.

My mother cried when I moved out my writing desk into Nathan’s basement apartment, filled with books piled on the floor. After graduating, Nathan and I travelled together, visiting art galleries in Paris and Rome, and viewing the paintings and archaeological sites that inspired many of the poems in my first book Hacker Packer. We then moved all our books to Iowa City, where I started my MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Nathan read poets like Kay Ryan, Ange Mlinko, Paul Muldoon, Lucie Brock Broido. I read my instructors Mary Szybist, Mark Levine, Elizabeth Willis. We encountered visiting writers like Ben Lerner, Denis Johnson, Ariana Reines, and bought all their books, and had them signed to Nathan and me, or just Nathan, or just me. At the end of my MFA, we moved all our books back to Regina, to a bedroom in my grandmother’s old house where we lived with my brother and his girlfriend.

After a year adjuncting in Regina, I abruptly moved to Toronto, upending my life and Nathan’s in the process. I took the Ariana Reines with me and Nathan moved to Japan, taking the Lucie Brock Broido there. He sent me poems he was reading, I sent him books back. He read the manuscript of my second collection Drolleries. When I read from the book in Regina, Nathan was already in Japan, but my parents came to the launch, something they rarely did because I got so nervous. The last time my mom had come to one of my readings, surprising me at the Cathedral Arts Fest, I’d started crying when I looked up and saw her sitting there. This time, my mom recorded the entire reading, taking selfies with my dad. When I got back to Toronto, she told me that the book, where I’d included some of her dreams and worries, had made her feel important.

In Toronto I tried to stop buying fiction, except for those books belonging to friends. Poetry was what I read and re-read and I took advantage of Toronto’s library system, obsessively scrolling on the Libby app on my phone. I struggled to adjust to a new city and I’d speed-read books, failing to take in plot or character beyond a vague sensation, but gaining a moment of distraction, a line that resonated with the malaise I was experiencing. Each time I visited home, I’d take a few books back to Toronto with me, privileging poetry, because I could fit more poetry books in my suitcase. I met an architect named Kourosh, and we started dating, and expanded the library in my studio apartment at 100 Spadina Road, a building designed by Estonian architect Uno Prii, which fascinated us both. I started taking Farsi classes, slowly learning a new grammar and alphabet, a new joy in language and metaphor. When the pandemic started, I began writing about the spaces we inhabited indoors, guided by Kourosh’s architectural eye. My poems became more fragmented, though I returned to the caesurae of alliterative verse.

When my mother died suddenly in September of 2020, I turned to poetry once more. I opened Rilke’s Duino Elegies, and the poet Aislinn Hunter sent me Rilke’s The Dark Interval, his collection of letters written for grieving friends. I entered correspondence with friends and poets who had lost their mothers and on their recommendations, read Betsey Warland’s Bloodroot, and poets like Denise Riley, Mary-Jo Bang, Marie Howe, Brenda Hillman, Linda Gregg. That year, Brick published Andrea Actis’ Grey All Over and David Bradford’s Dream of No One But Myself, contemporary poets reckoning with the complications of family and grief. I read memoirs of loss compulsively, drawing a connection between my obsessive reading practices and the attempt to distract myself from the chaos and violence of the neighbourhood where I grew up.

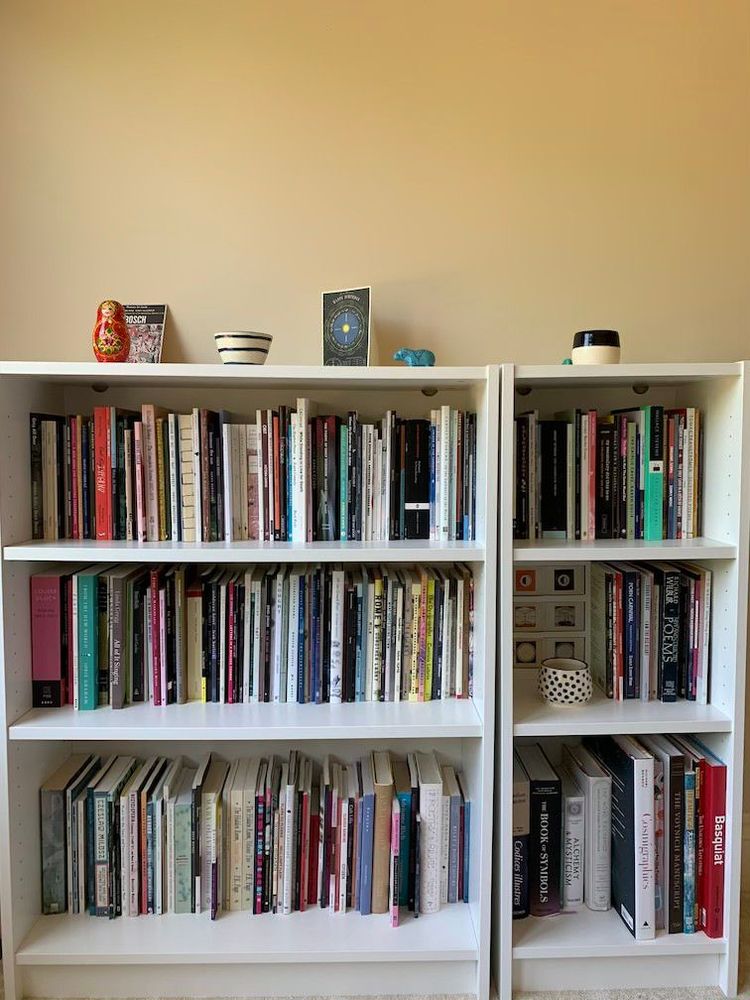

Books for me have always been about finding recognition, consolation, the feeling I wasn’t alone. Poetry has helped me to survive, for when there is nothing left, there is poetry. When I stuttered too badly to speak, I could find the right sounds to ease out my voice. I could hide from what felt scary or overwhelming in form. But when my mom died, I lost some of the joy and curiosity I had for language. My poetry now feels fragmented, dissonant, obscure even from myself. A year after my mom died, I moved to Brooklyn to start an MFA in fiction, seeking a change of location, a fresh start, a break from the claustrophobia I’d been feeling in Toronto. I didn’t take any books with me, tried to avoid New York’s many used bookstores, but I’ve somehow accumulated more poetry, chapbooks, and journals that are starting to fill the inset shelves in my Brooklyn sublet.

My books are now scattered between my childhood home and my brother’s house in Regina, Kourosh’s family home in Toronto, and our apartment in New York. I don’t know where my library will end up, if one day my books will form a coherent collection, or will scatter to more places where I live for a while. Often when reading a book on my phone, I’ll experience a vague déjà vu of having read certain sentences before. More often than not, my notes inform me that I have, or that I started it and gave up, not in the right mood or mindset for the book the first time around. I’m sentimental about my reading habits, feeling a rush of tenderness for a book I bought my mother for Christmas, or one I read as a child but can no longer remember the title, the blue book about a misbehaving mermaid my grandmother used to read me. Maybe I inherited this nostalgia. In the final years of her life, my mom became obsessed with finding a childhood book about fairies, which she described as a giant hardcover with fanciful illustrations. We tracked down A Day In Fairy Land on eBay and she was overjoyed to re-visit the book, though she said it was smaller than she remembered. I know that books are only physical objects. Stories and poems, like those we love, live inside us, not in their physical presence on this earth. I hope that my mother knew how important she was to me. I hope I carry the best parts of my loved ones inside of me, as treasured as my favourite books.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

McFadzean, Cassidy . “A Day in Fairy Land.” Shelf Portraits, 2 February, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/a-day-in-fairy-land. Accessed 22 June, 2025.

APA

McFadzean, Cassidy . (2023, February 2). A Day in Fairy Land. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/a-day-in-fairy-land

Chicago

McFadzean, C. “A Day in Fairy Land.” Shelf Portraits, 2 February, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/a-day-in-fairy-land.

Cassidy McFadzean

Cassidy McFadzean was born in Regina, earned an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and currently lives in Brooklyn. She is the author of two books of poetry: Drolleries (McClelland & Stewart 2019), shortlisted for the Raymond Souster Award, and Hacker Packer (M&S 2015), which won two Saskatchewan Book Awards and was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. Her new chapbook Third State of Being is available from Gaspereau Press.