I want to build you bookshelves my partner confides after a few months of dating. We’re entwined in my turquoise sheets in the bright grey light of a spring morning that my one translucent curtain fails to block out, nibbling on olives and cheese in between bouts of honeymoon-stage morning sex. The door is closed to shut out my roommates and the outer world, to give us this small cocoon as we begin to build our rapport. Their wish to build me bookshelves is an intimate pledge, more telling than any kink or desire we’ve shared so far. Their need is pleading in a way that mostly strips it of butch bravado. They want to bring me order because it’ll bring them pleasure.

My bedroom houses several towers of books. There are piles on my desk, drawers and both bedside tables. A handful of uneven columns the height of a four-year-old child teeter to the left of my desk. Sometimes they collapse when I’m riffling in search of a particular title and sometimes they fall over of their own accord, jolting my nervous system in a frantic moment where the boundaries between animate and inanimate objects dissolve.

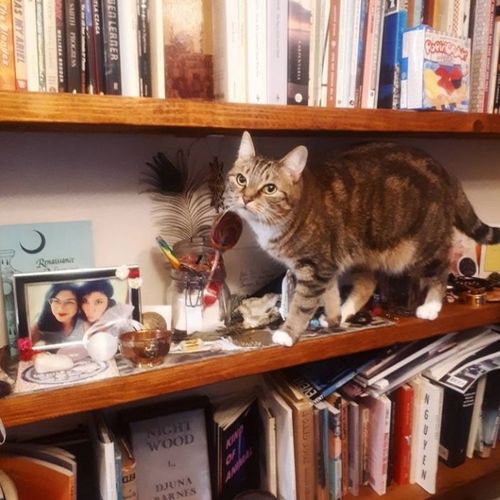

Perched on top of a cabinet leftover from the artist I inherited the lease, some IKEA furniture, and a decent mattress from are my special editions—limited first edition hardcover run of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets stashed in an Indigo bag, a UK 1936 first edition of Nightwood by Djuna Barnes with copy by T.S. Eliot, the Malomar self-published edition of Coeur de Lion by Ariana Reines, an American edition of Sylvia Plath’s Ariel from 1966 (first edition but not first printing). I instruct curious visitors: These books don’t leave my room.

A modernist scholar I once worked under dismissed collecting rare books as treating the book as fetish object. I’m open to investigating the classism that fuels bibliomania, but why dismiss the pleasure of a fetish? I treat both my sex toys and special editions with care. Of course he was the kind of Marxist who plays golf.

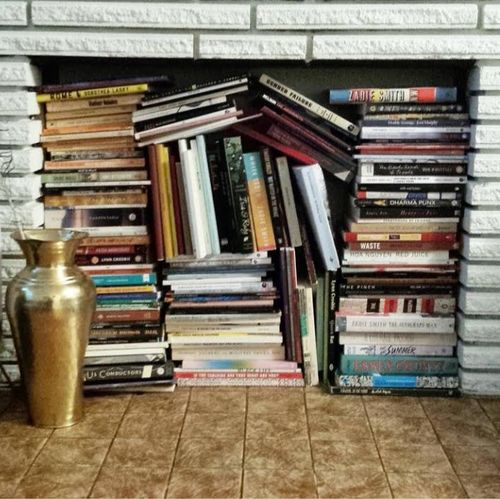

Not all of my books live in my bedroom. Some sit in boxes in my parents’ Southern Ontario basement, waiting for the day I’ll reclaim them. But I don’t have plans to return to rural Ontario anytime soon. In the living room of the Vancouver apartment I share with two roommates, we wedge books into the hollow of the false fireplace. My collection—American poetry, queer nonfiction, feminist graphic novels, Canadian small press—plays nice with my roommates’ Zadie Smith, Miriam Toewes, Patti Smith, Whitney Biennials from the early aught’s, encyclopedias of herbs and human anatomy.

Friends come over, set down their drinks on the scratched hardwood floor, and mull over the titles in the fireplace. Usually they ask for a specific author or abstract suggestion, and I tug something out of the stacks to press into their hands.

✼

When I lived alone on an island, my books filled a squat bookcase and then lined the walls of my living room. West coast insulation is thin and I’d like to think those books added a subtle layer of warmth. I outfitted my one-bedroom apartment and body with vintage gold from Victoria’s abundant second hand stores—items throughout the decades get shipped to the island and never leave. I didn’t like living on Vancouver Island, but at least I looked glamourous, making old fashioned cocktails and playing sad, slow Lana Del Rey covers on an enormous early twentieth-century upright piano borrowed from my friend who moved to Scotland.

For an art project, another friend documented women in their homes and so she came over to photograph me amongst my things. For the final art show, she selected an image of me seated in a grumpy green chair, affectionately nicknamed Swamp Thing. In the photo I peer at her through a dainty pair of opera glasses flanked by my desk and towers of books. A laptop and a swirl of papers sprawl all over my desk to the left of me and the wall of books nestle and descend upon my right. When we posted the photograph to Facebook I received many offers from people who wanted to sell me their bookcases.

I like bookshelves and would like to house my library in a more systematic and grown up way. However, my collection doesn’t naturally feel neat or static—it’s an organism that expands and keels over as I bounce between titles. The books need to live together in these makeshift clusters because usually I’m working with them or thinking through them in constellations. Canisia Lubrin’s Voodoo Hypothesis lives under of Marcela Huerta’s Tropico for a while and then needs to sit on top of Jillian Tamaki’s SuperMutant Magic Academy. And then the tower falls and reveals to me Chelsey Minnis’s Poemland. Groupings form with intention and by happenstance, which could describe how I write poems.

✼

Honestly, the clutter has more to do with instability or maybe just hypermobility. From summer 2014 to spring 2015 I moved through 9 apartments and through 4 different cities. I lived with the notion and reality that books don’t have an established home. Like me, they needed to mobilize quickly from each spot to the next. I packed them into canvas bags and slung them onto my shoulders as I boarded buses, trains, subways, and planes through the Northeastern states and eastern and western Canada. Schlepping books was necessary as I was researching a dissertation on American literature and writing a collection of poetry while I moved.

When I finally landed in Vancouver in 2015, I progressed through several sublets before settling into the top floor of a Triplex known for hosting huge Halloween parties thanks to the skater boys downstairs who worked as event organizers for a long-boarding company. In this triplex I completed an unholy East Van roommate trinity—a hardcore punk, a freak folk bassist/clown and a witchy poet. This is the apartment where we stashed our books in the faux fireplace under the mantel of empty brass picture frames, seal bones and bat taxidermy. This is the apartment where, after walking for an hour in the March rain at 3 a.m., I first brought my partner home to my torn sheets and towers of books after meeting at an awkward queer sex party. Even though my mess didn’t initially scare them off, I set out to buy new sea-foam sheets from Winners that week in preparation for our next date.

✼

A year later I move into a two-bedroom apartment with my partner, their sister and two coddled tabbies just a few blocks north from the Triplex on Commercial Drive. My books remain in boxes in the living room for a few months because we need more bookshelves and my partner promises to follow through on making them for me. We plan to install bookshelves and a communal family altar into the wall beside the dining room table. The stud finder zings red with warning because of the electrical wiring hidden behind the plaster, but my partner’s father says it should be safe to drill. He is a geologist who makes a living telling diamond companies where it is profitable to drill so we trust his expertise on the matter.

Without access to my collection, I immediately borrow hordes of books from the library and stack them on my desk in the living room and take them with me to the café, park, beach. At Wreck Beach a beer can inexplicably punctures and leaks in my backpack, waterlogging Casey Plett’s Little Fish and Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead. I haggle with a nonchalant librarian over the fines. Ashamed by my disaster-prone touch that rumples everything I encounter, I bring the warped books home wrapped in a special plastic bag from the public library.

My partner and I build bookshelves slowly with lumber stolen from a construction site for condos that are set to tower over the final pink punk house on Victoria Drive. We line the planks on a small white table in our makeshift yard. I sit on each plank, pinning them to the table, while my partner saws them into the appropriate lengths. The first time they cut with the circular saw—also stolen from the construction site—it kicks back against the wood and its hinge swings loose. My adrenaline spikes. I make very deliberate and steady eye contact with my partner when I tell them to make sure everything is in its place before they try again. They lock the saw’s hinge and try again. I breathe and then sit on the plank so it doesn’t move and watch the saw swiftly eat through the plank.

I’m not uncomfortable around saws—my middle and high school education in small town rural Ontario made shop class mandatory. While those skills lie dormant in my current life as an urban poet, I’ve tried my hand at wood, metal and electrical shop. The burly shop teachers of Georgetown District High School instilled a severe respect for tools and proper safety protocol—myths of students with lost thumbs and eyes replaced traditional syllabi. Sawing through stolen cedar with a stolen circular saw on a rickety table just before the sky breaks into rain deviates from the safety protocol I learned from that wide hall of Misters, their unruly beards and sweat-stained golf shirts tucked into acid wash jeans. I liked shop class but was miffed that it being a requisite course at GDHS meant I couldn’t take more art classes. As I pin a plank down with my own weight, my partner, who spent their youth training professionally in the soccer fields of West Van, tears through the wood. I’m aghast at how confidently they wield a saw with little to no training.

We stain the wood on sunny July days, leaning the planks against our apartment building to dry. Mixing dark and light stains together, we coat the lumber in a toxic caramel glaze. We process moving in together, flailing friendships, and knots in our polyamorous web while lightheaded from the fumes. Sometimes the stain bubbles and we glide our stiff paintbrushes over the wood to soothe the noxious ooze that’ll render these planks more beautiful.

✼

At the end of summer I attend Witch Camp for the first time. It lasts a week and takes place on an educational camp ground in Squamish. I have no cell reception except for on the dock of a small lake that jagged conifers pinch into a misty chamber. I don’t like Witch Camp—making meaningful eye contact with strangers and being told to grieve for the earth strike me as hollow. Enforced intimacy feels unsafe to my body and being told how to feel makes me cranky.

The goal of Witch Camp appears to be connection, but my problem is that I’m already always a little too connected to my surroundings. My favourite day is when I skip my Elements of Magic course and read Francesca Lia Block’s Weetzie Bat books on the dock.

I notice something curious at camp: I’m homesick for the first time in my life. I’ve never experienced homesickness before, neither as a child nor an adult. I’ve felt grief for the safety I haven’t had, but that’s a different kind of longing, one with shadows and shame. I’m struck by how this particular ache unfurls, radiating from a sore, vibrant heart. I tell my friends I’m homesick while treading water in the lake. I miss my Daddy. They smile and think I’m being cute, but I’m actually experiencing a physical throbbing that boils through my head, core and limbs.

During book tour I wished for my familiar nest of a bed with all my things nearby and the ability to close a door and be by myself, but I didn’t physically feel hurt or weighed down by the pining. I’ve felt a stretched twinge from friends and lovers spread across competing, challenging geographies. I’ve been tired from the enduring slog of moving apartments and cities every few months. But now this sensation of missing my home emerges out of a newfound corridor in an emotional landscape I thought I’d already plumbed.

While I chant and wiggle my body in a cold field with 80 strangers, my partner and their father finally install our bookshelves into the wall that’s covertly, but not dangerously I’m told, buzzing with electricity. Four eighty-eight inch cedar planks secured to the wall to hold all of my library. Afterwards, they toast to the shelves with craft beer and send me a photo I won’t receive for hours. Bolting through the forest to the lake after evening ritual, I catch a couple meager cell service bars on my phone. I sprawl onto the dock of the dark lake under the dark sky with my tiny glowing screen. In the photo my partner has sent I see their grinning triumph from completing the task they had set out to do when we first started dating.

This chore’s simplicity and care bewilder me. I didn’t know my books, and by extension myself, were allowed to splay and be held so beautifully. I didn’t know I was entitled to take up space and even make it serve my needs. Now I can walk right up to my shelves and pluck whatever title I’d like while writing. I can see the range and gaps of my library, evidence of my reading, thinking, and living standing securely on planks my partner and I cut and stained ourselves. I didn’t know love could manifest tenderly in physical space until my partner offered me this form of care and I accepted it. To build a home where I can unfurl, that will bear the weight safely.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Barclay, Adèle. “A Spell for Holding.” Shelf Portraits, 25 June, 2021, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/a-spell-for-holding. Accessed 11 February, 2026.

APA

Barclay, Adèle. (2021, June 25). A Spell for Holding. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/a-spell-for-holding

Chicago

Barclay, A. “A Spell for Holding.” Shelf Portraits, 25 June, 2021, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/a-spell-for-holding.

Adèle Barclay

Adèle Barclay’s essays and poems have appeared in many North American journals and anthologies, including Vallum, The Heavy Feather Review, Cosmonauts Avenue, The Walrus, glitterMOB, The Pinch, PRISM, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of the 2016 Lit POP Award for Poetry and The Walrus’ 2016 Readers’ Choice Award for Poetry and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her debut poetry collection, If I Were in a Cage I’d Reach Out for You (Nightwood, 2016) won the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Her second collection of poetry, Renaissance Normcore (Nightwood, 2019) was nominated for the 2020 Pat Lowther Award for Poetry and the ReLit Award and placed 3rd for the Fred Cogswell Award. She was Arc Magazine’s 2018-19 Poet in Residence, Canadian Women in Literary Arts 2016 Critic in Residence, and the University of the Fraser Valley’s 2020 Writer in Residence. She is an editor at Rahila’s Ghost Press and teaches literature and creative writing at Capilano University.

Author image by Alistair Henning, www.AlistairHenning.com.