Back when I was a furniture mover, we would sneer at how the customers organized and treated their books—the particle board that showed complete disrespect for the reading experience; the unintellectual impulse to load shelves with tchotchkes; the tackiness of stacking books one on top of another. As a punishment, when we got to the new house, we entombed these people with boxes of their own books, knowing they’d never read their way out.

But now, I’m the one whose shelves are a mess. This organized chaos is not by design, and it gets worse the more I try to fix it. Bookshelves surround my bed because that’s what the layout of our apartment suggests. This runs against the advice of my allergist, who says I shouldn’t keep anything that gathers dust. I never told her I’m a writer and that we surround ourselves by what’s deadly; to apply her advice correctly would mean getting rid of everything I own. But she’s right that books are the danger here. In the Bohumil Hrabal novel Too Loud a Solitude, a paper crusher recuses discarded books and stacks them around his bed, which he imagines breaking the shelves and killing him in his sleep. I don’t think a filing system would’ve helped him.

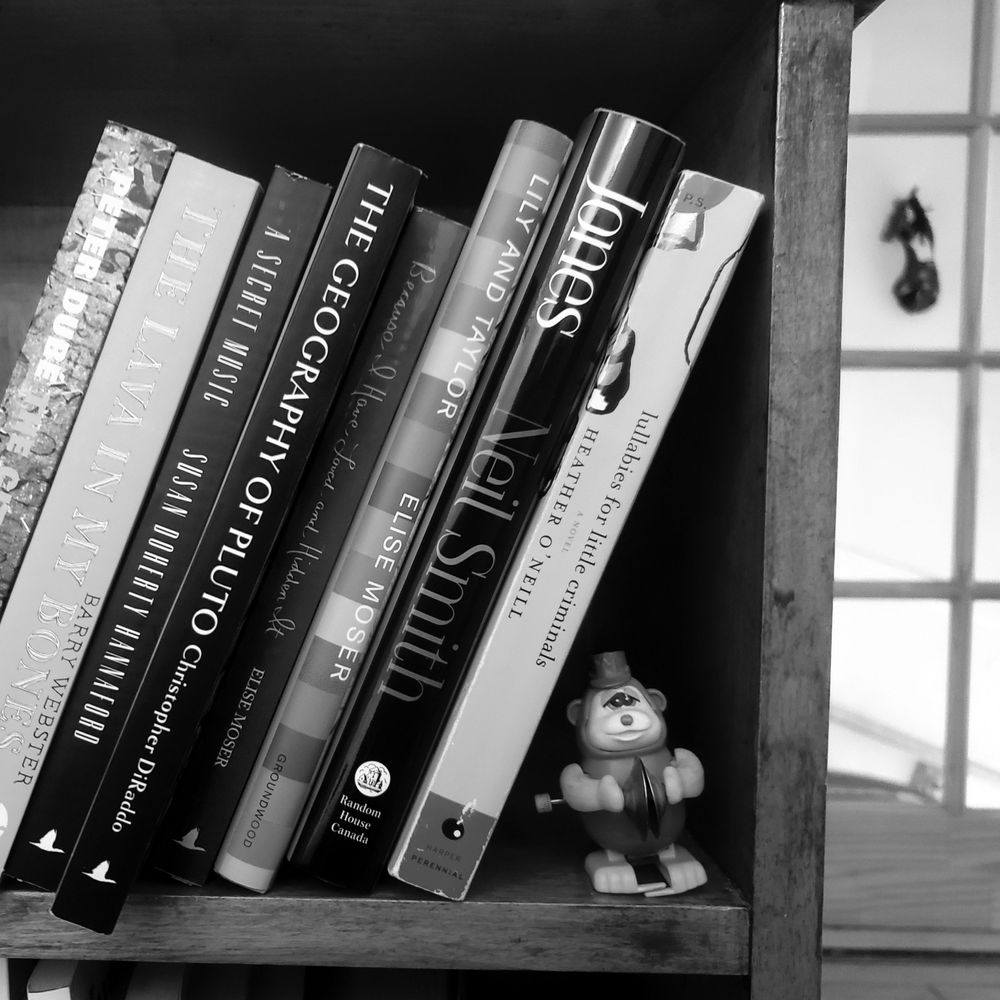

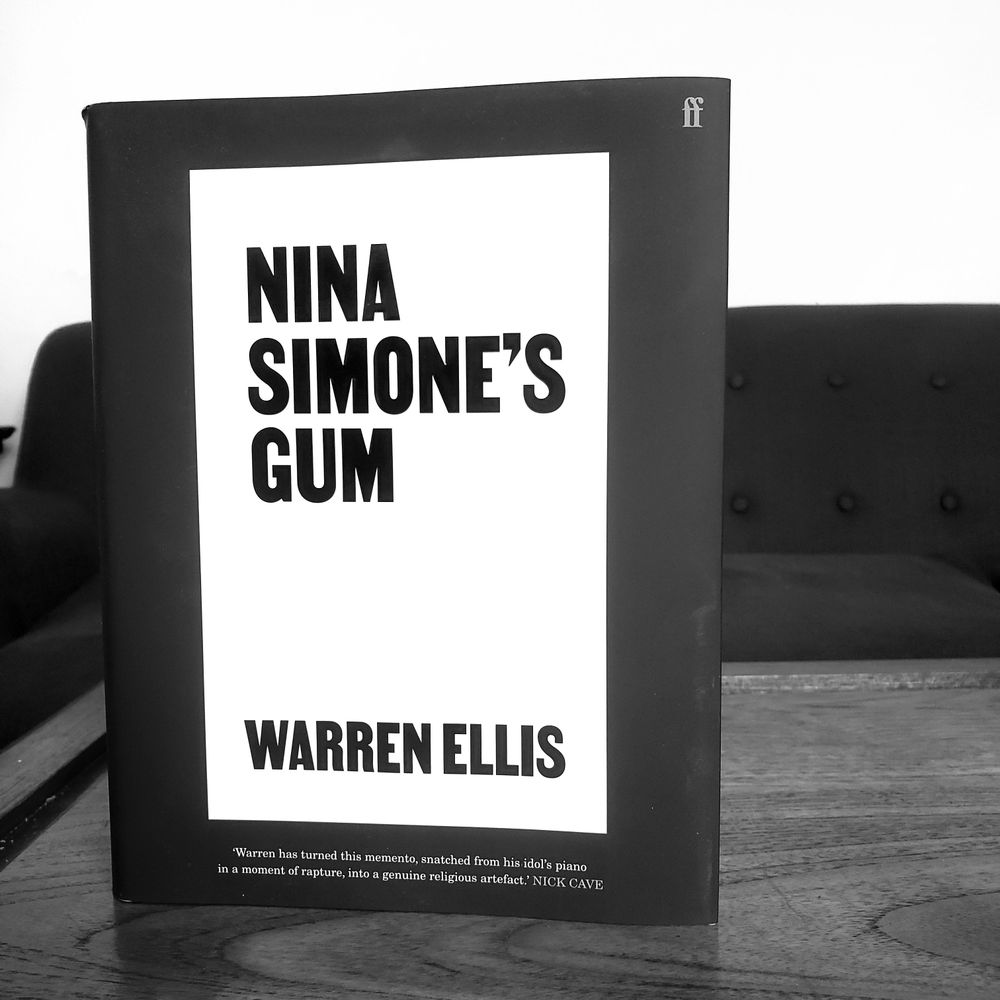

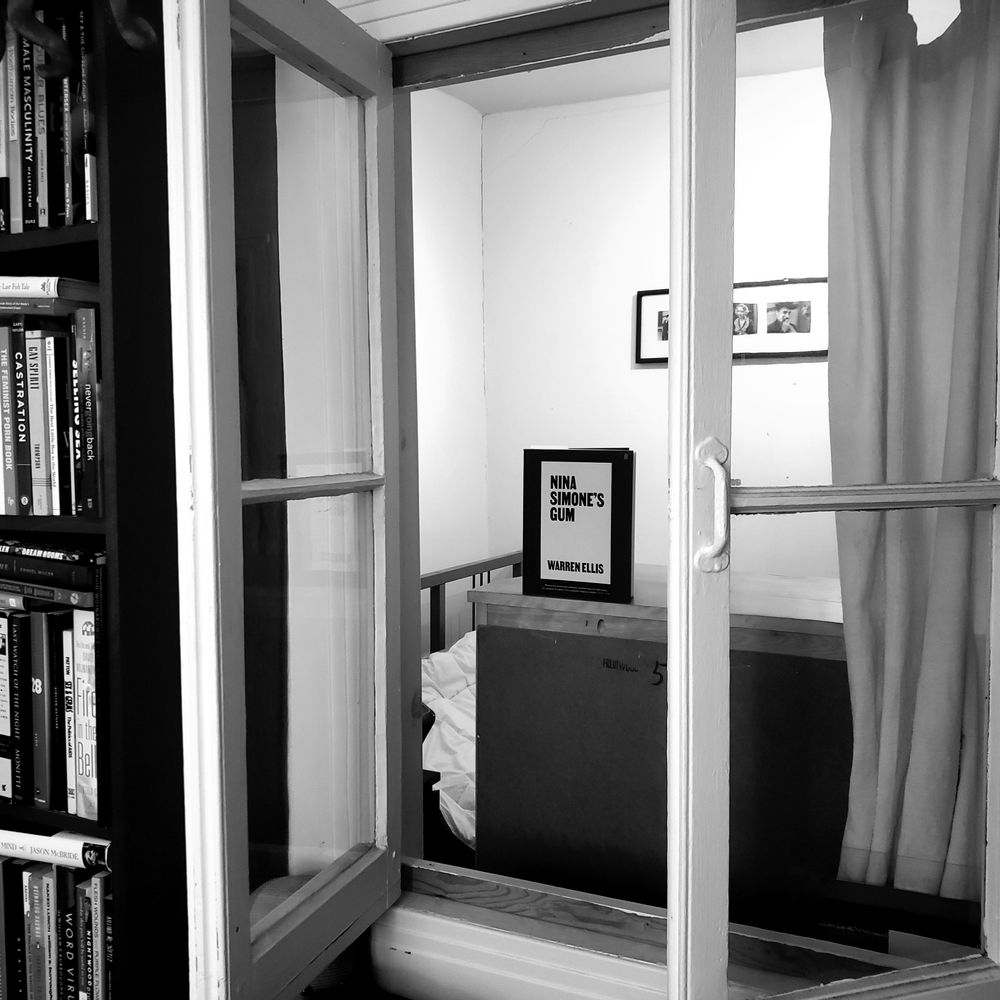

My partner Mark and I keep our bookcases in adjacent rooms, where they hug either side of the same wall. Our libraries are mirror images of each other, pierced by a little connecting window. Over the years, when one of us has asked to borrow a book, a disembodied hand will emerge through the window holding the book like a lit cigarette that, in all probability, will never be passed back. I am the one who never passes back, so it’s no coincidence that Mark’s hand doesn’t appear as often. “You still have Nina Simone’s Gum by Warren Ellis,” he’ll tell me late one night, as if to explain the new window dynamics. But the problem is obvious: Mark’s books are sorted masterfully. Apex predators huddle together with a keen awareness of their place in the alphabet. There’s AIDS history as told through novels, through memoir, through anthology. Illustrated coffee table books arranged by the size of the tables they would fit—if we were the kind of people to put books on coffee tables. I’ve never sorted my books the way he does.

But once I’d started writing my first nonfiction book, my lack of a system started to bug me. I could no longer spend hours hunting for individual books, and I needed quicker access to my sources. So, one night, I pulled all the books off my shelves into great heaps on the floor so I could do some binary separation into fiction and nonfiction. I wasn’t entirely successful, since not every book I own declares a stated preference for fact. On the topic of blur: the dust mites got me that night and I wore a mask to control the sneezing fits. I managed to collate the essays and collective histories and lit journals in a way that I could trawl easily. It’s still far from being a system, per se.

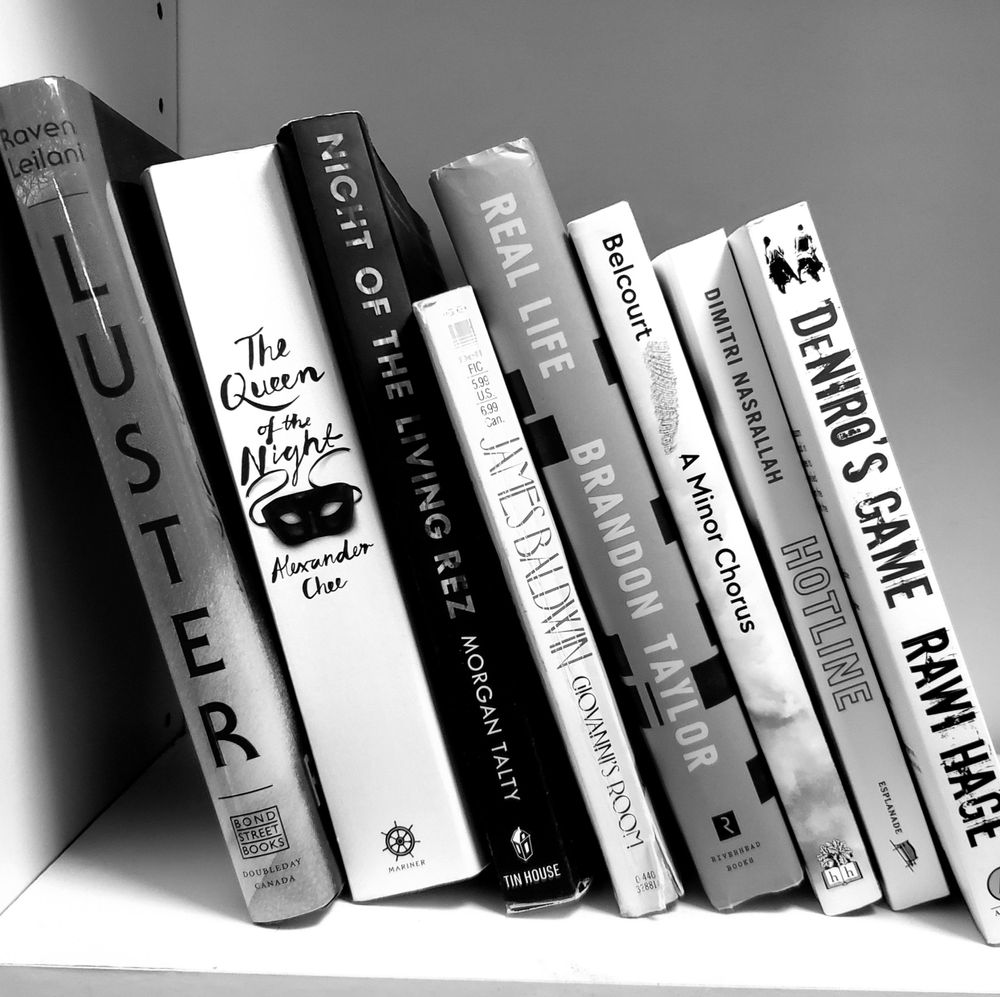

I didn’t have the energy or lung capacity to do fiction that night, so I jammed the novels and short stories all back on the shelves (which are loaded with tchotchkes, of course.) I haven’t seen Too Loud a Solitude in years. It’s lost and will remain so, probably behind a Proust tome or wedged between the shelf and the particle board backing I never thought I’d own. But maybe there’s something else at play here. I’m currently finding my way back to writing novels again, and my approach can’t be too direct. I need some obliqueness—some accident—in the way I connect with fiction right now, either my own or that of other writers. The fiction shelves are closest to the bed. Sometimes, late at night, I’ll pull the book closest to me to leaf through. It’s usually something I forgot I had. Perfect alphabetization doesn’t let me indulge in this twin pleasure of forgetting and rediscovery.

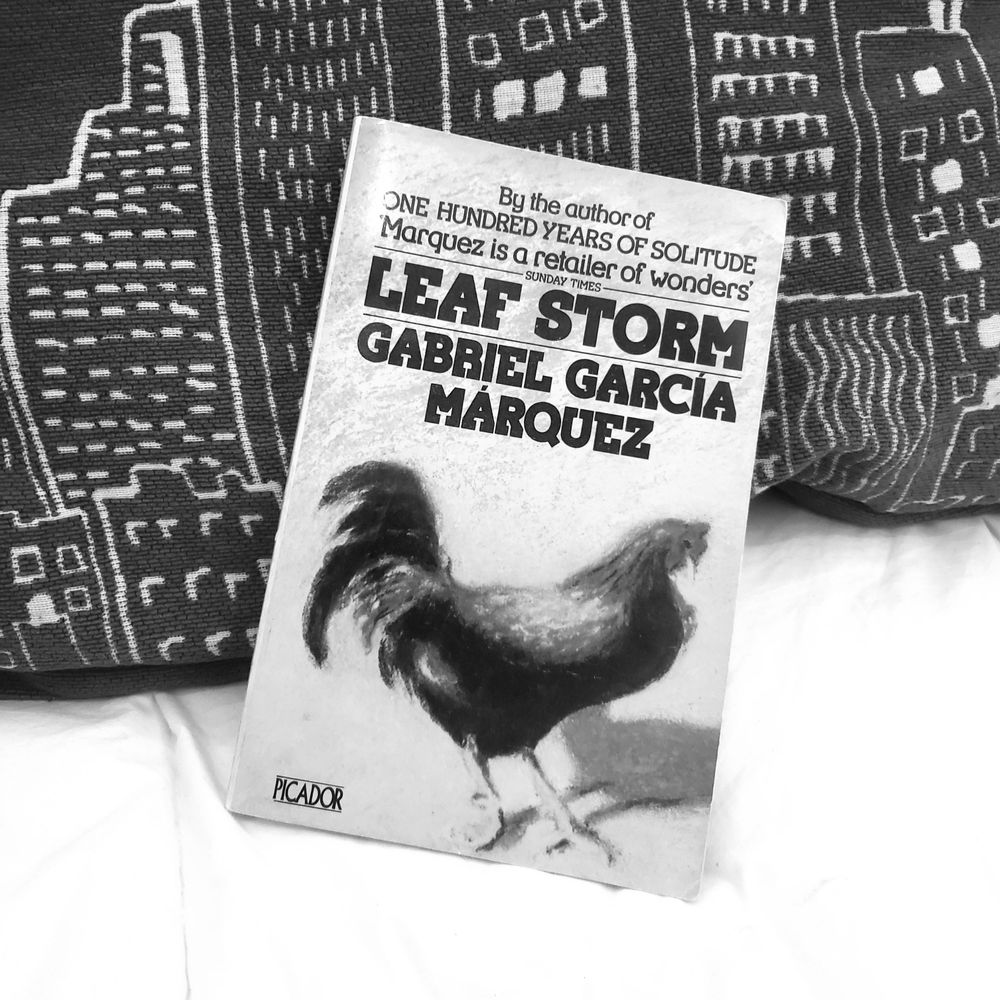

But if I’m too sleepy, I won’t get up and grab anything. Instead, I’ll stare from my bed at wild groupings—a commotion of small press novellas, a disarray of poetry volumes of friends who’ve died, a tumult of uncorrected proofs, my own output—and marvel at who sits beside whom. In real life? They’d claw each other to the bone. At a bookstore? Impossible, categorically. My refusal to impose order has placed these authors in tight, inescapable conversations with one another, ones I will never hear because I get too sleepy and drift off, and dream of the characters in Leaf Storm by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the silent ones who observe and observe and never say a thing. The ones who know. When I awaken in the morning (for the shelves have not, at this stage, yet sunken and smothered me) the fiction may have rearranged itself into a new and beautiful cacophony.

Maybe today is the day I push Nina Simone’s Gum back through the window and wait for a hand to receive it.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Cox, Daniel Allen. “Impossible, Categorically.” Shelf Portraits, 14 July, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/impossible-categorically. Accessed 13 August, 2025.

APA

Cox, Daniel Allen. (2023, July 14). Impossible, Categorically. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/impossible-categorically

Chicago

Cox, D. “Impossible, Categorically.” Shelf Portraits, 14 July, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/impossible-categorically.

Daniel Allen Cox

Daniel Allen Cox is the author of I Felt the End Before It Came: Memoirs of a Queer Ex-Jehovah’s Witness, and four novels nominated for the Lambda Literary, Ferro-Grumley, and ReLit awards. His novel Mouthquake was one of twenty-seven works selected for inclusion in QuébeQueer, a fifty-year overview of queer cultural production in Quebec. Daniel’s essays have appeared in The Guardian, Electric Literature, Literary Hub, The Malahat Review, Maisonneuve, Catapult, TriQuarterly, The Rumpus, The Florida Review, and Fourth Genre. His essay “The Glow of Electrum” was nominated for a 2021 National Magazine Award in personal journalism and was named a Notable essay in The Best American Essays 2021. “You Can’t Blame Movers for Everything Broken” has been selected for Best Canadian Essays 2024. Daniel is the 2023 Constance Rooke Creative Nonfiction Prize judge.

Author photo by Alison Slattery.