In Memory of William Lloyd Clarke (May 20, 1935—August 30, 2005)

Growing up in the working-class North End of Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the 1960s, it was magical for me that my family’s living room boasted bookshelves, including space for a set of the Encyclopedia Britannica, which, later, in the 1970s, my father, Bill Clarke (1935-2005), peddled as a part-time gig. As a boy, I could only direct my eyes over the lurid, day-glo-coloured covers of shelved dust jackets or the paperbacks, wondering why the Playboy Book of Crime and Suspense (1966) featured a scared, naked man with a sword or why Bill Styron’s Confessions of Nat Turner (1968) featured a black angel—in silhouette—thrusting a sword. I could only view my father’s book collection—or home library—as a set of grand and mysterious texts—especially all those bound in leather and redolent of shoe polish muddled with truffle. Yet, their doubtless secrets were spellbinding for me because he was the first example of an intellectual—and a household artist—that I ever knew. Indeed, he worked for Canadian National Railways in Halifax—at a humble job; not a porter, but merely as a black guy trundling luggage and linen to-and-fro the overnight train—the Ocean Limited—shuttling between Halifax and Montreal. Although he was merely a prole, he always went off to work with a book in his lunch pail; and, on weekends, he would paint conventional portraits and landscapes, rendered unconventional by his application of Testors model-kit paints to glass behind which he would place tinfoil. The resultant images shimmered. Other boys could brag about how their dads were stronger than mine; how theirs could “beat” mine. Fine. I cherished Bill Clarke for his smarts: I figured that he was smarter than the other dudes in my community, whatever their background. My regard for him made me want to penetrate (I use the incidentally Freudian verb deliberately) the meaning of the books that he chose to enshrine in our household library.

My mom—Geraldine Clarke (1939-2000)—was a teacher’s college graduate, while my dad was a Grade 10 dropout. However, her reading tended to be romance-and-scandal magazines like True Confessions, fare which did not appeal to my nerdy (but not “sissy”—I think) self. Even so, it was she who got me my first library card (when I was 8) and who, when I was a teen, loaded me down with T.S. Eliot’s Selected Poems, so as to encourage my tyro ventures in poetry. (Yet, she could not have known that, by age 19 and 20, I’d prefer Pound, Baudelaire, the Beats, and Black poets; for, by then, for me, Eliot had dwindled into the image of his own Prufrock—an effete prig, with erectile dysfunction and a Babbitt-vacuous, bourgeois lifestyle.) I did read secretly a bedside novel of hers about a cigarette-saleslady who, despite carrying a tray loaded with cigs, kept getting bent in compromising positions over desks and in cloakrooms. But, failing to mention aliens or dinosaurs, or Superman or Batgirl, it could only rest in my memory as an intriguing deviation—or deviancy—that was also a dead-end.

Anyway, once I had the library card, I virtually moved into the Halifax North End Memorial Library, about three blocks from my home. On weekends, I’d borrow an armload of books on Saturday morning, read through them, return them the same day, and then pick up another armload before closing time. I was such an aficionado of the stacks on the “Juvenile” side of the library that, by age 10, I’d exhausted the “kids’ stuff,” and, under the watchful eye of the Head Librarian—Miss Dee Amyoony—was permitted to cross over to the “Adult” side of the library, a liberty that one usually had to be 15 to enjoy. In that redoubt, I could delight in the Hitchcock suspense-story anthologies or Sci Fi tales featuring derring-do and distressed damsels. (Only later—in my teens—did I delve into the Black Panther screeds versus “Whitey” or check out Bob Dylan’s interviews, all verbal slapstick or Tarantula-Beat lunacy.) Miss Amyoony (pronounced A-moony) could easily double-check my choices and rule out anything that might be potentially corruptive of my boy’s imagination. Even so, despite her prudent supervision (which wasn’t absolutely necessary because I couldn’t figure out, for instance, what Winston Smith and Julia were doing in bed together in George Orwell’s 1984), I discovered the word pudenda in a mystery novel and had to get access to an adult-level dictionary to find its meaning. (Ah, the origins of scholarship!)

Feeling chuffed and emboldened by my ability to navigate the “Adult” side of the library, I could now turn my eyeballs back to my father’s books in our home, to peruse and decipher his interests, partly so I could feel closer to him, a stern man who beat my mother and my brothers and me, but who I also loved profoundly and respected (feared) greatly. I thought that if I could show that I agreed with his tastes, he would have less reason to treat me to a thwacking for some (I’d say) minor infraction. So, I hunkered down to the Ian Fleming-authored James Bond adventures “canon.” I knew that my father idolized the Bond character, for, in the mid-to-later 1960s, we went frequently as a family to catch a cinematic double bill of Thunderball and Goldfinger or Dr. No and From Russia with Love. Yes, the puns and double-entendres were beyond my ken; and I couldn’t see why “dames” should take away screen time from nifty gadgets (though I was sorry that Karin Dor—as “Helga Brandt”—got fed to piranha in You Only Live Twice). Still, because my father prized his Bond paperbacks, I decided to power through the lot, though I was but 10. I’m 62 now, but I still remember reading a chapter, in Thunderball, entitled “How to Eat a Woman.” Yep, I missed porn-loving Fleming’s salacious reference to cunnilingus, which is not the act depicted. Nevertheless, that title inflamed my curiosity enough that it remains a go-to, literary memory. However, I was soon introduced viscerally to adult sexuality for, among the Bond trove, my father had secreted—in plain sight (so to speak)—a romance about a loving wife who, at the request of her impotent, elder husband, agrees to have liaisons with studs, to render herself a serial mistress and hubby a constant voyeur. Despite the “scrofulous” (see Robert Browning) novel’s explicit photos of members staffing orifices, I remained somewhat confused about the purpose of the configurations. Sure: The tale was “dirty,” but I ignored the photos and read the story, which was all about the December-May couple finding ways to ameliorate the husband’s inadequacy via the ministrations (prostrations?) of the lovers who were so very eager to oblige the wife.

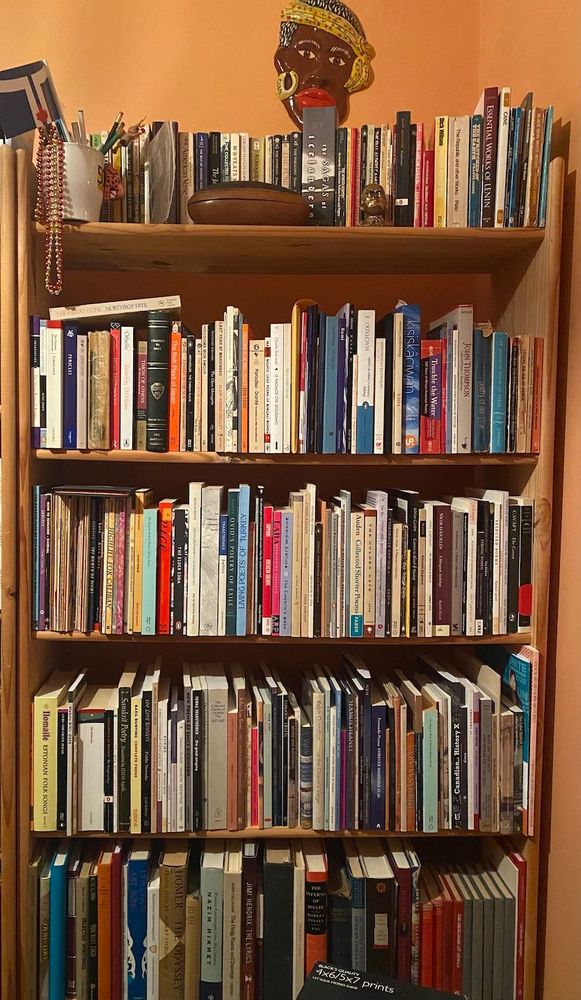

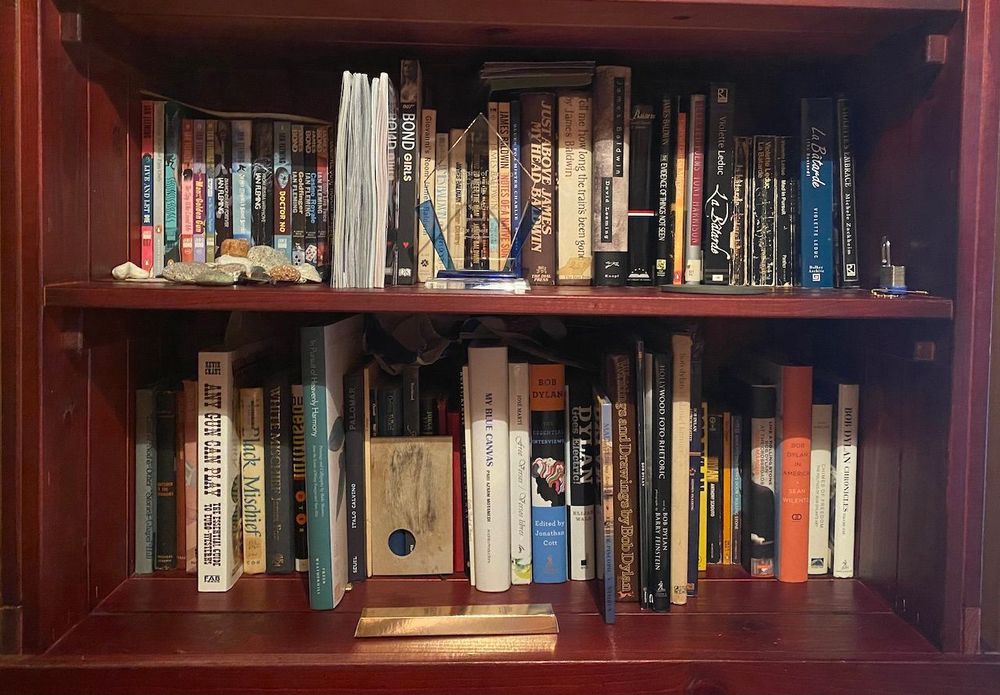

Although I was too young for the pornography—or “eroticism”—to register as anything other than wardrobes playing peek-a-boo with body parts; and though my focus was Ray Bradbury and Robert A. Heinlein, or Edgar Allen Poe and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, or The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, I can now look back on my 10-year-old self and realize that my literary interests then—in trying to bond, via books, with my father—were consequential to both my own construction of a home library—and my ferrying with me—through decades—many of my father’s books. So, my home library—once a small bedroom in my three-bedroom, two-storey, Toronto semi-detached, includes these stalwarts of my father’s shelves: The Fleming Bonds (complete set), Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); Robert W. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974); Norman Mailer’s The Presidential Papers (1963), Clem Kovak’s Casebook: The Interracial Sexualists (1971)—which is a no-holes-barred, black & white, interracial sex-romp; Theodore White’s Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon (1975); Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice (1968); John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me (1961); Jesse Owens’ Blackthink (1970), which is a conservative rejection of Black radicalism; Bill Adler’s edited, The Kennedy Wit(1964); Donald Barr Chidsey’s They Sank the Lusitania (1967); Saul Alinsky’s Reveille for Radicals (1969) and Rules for Radicals (1972); Arthur Veysey’s Vietnam War reportage, Death and the Jungle (1966); Comer Clarke’s England Under Hitler (1963)—which deals with the German occupation of the Channel isles; Gene Gurney’s Great Air Battles (1963), covering all from the shooting down of the Red Baron (I recall that the Canuck ace credited for the “kill” had a bad stomach and liked to down milk with brandy before taking flight) to the vaporization of Hiroshima; Robin Moore’s The French Connection (1969), wherein the connection is in Montreal, not Marseille (as the movies pretend); George Grant’s Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism (1965); stevedore-philosopher Eric Hoffer’s The Temper of Our Time (1967); Allen Dulles’ edited, Great True Spy Stories (1968); Albert Mordell’s The Erotic Motive in Literature (1961), which my father likely bought in desperate hope that it would not turn out to be the Freudian and Jungian claptrap that it is; Hugh MacLennan’s Voices in Time (1980)—the sole Canadian novel in Bill Clarke’s collection, possibly appealing to him because MacLennan was once a Haligonian; Louis W. Collins’ In Halifax Town (1975)—a walking-tour guide about Halifax; John D. Harris’s The Junkie Priest: Father Daniel Egan, S.A. (1964); Elizabeth Willmot’s Meet Me at the Station (1976), presenting write-ups and photos of small-town Canadian train stations; James Baldwin’s essay, The Fire Next Time (1962), and his novel, Just Above My Head (1979); John Toland’s Adolf Hitler (1976) and the associated Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William Shirer (1960); my father was a paperboy during the latter years of World War II, so he lived it vicariously—yet viscerally; Sand Lesberg’s Assassination In Our Time (n.d.); Canada With Love / Canada Avec Amour (1982), edited by Lorraine Monk and published to celebrate the patriation of the Constitution with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms now inscribed; Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men (1946); Winston Churchill’s History of the Second World War (Time/Life edition, 1960); plus Webster’s Third International Dictionary (1961) and The Britannica Atlas (1974).

Along with the aforementioned Encyclopedia Britannica set and the Styron and Playboy books, my father also owned two works of poetry: Immortal Poems of the English Language (1952), edited by Oscar Williams, and which he likely acquired for his sole year of high school—Grade 10 (1952-53), and an awesomely peculiar—and quite pedestrian—anthology, New Voices in the Wind: Best Contemporary Poetry (1969), edited by Jeanne Holyfield and G. Yvonne Jones, which presents “more than 500 new poems from the pens of 300 authors,” presumably American and utterly dismissable. For instance, Alan L. Gansberg gets to shine, but Allen Ginsberg is AWOL. Then again, when I had started to write song lyrics and then poetry, ages 15 to 16, my parents were divorced and I was living with my mom. However, I still spent summer or winter weeks with my father, and, on one such occasion, I plundered New Voices in the Wind, which is a cranky mash-up of Modernist and Beat and Victorian modes. I don’t have time now to find—among the 500 poems—the single image that I remember: A helicopter exploding in “orange surprise”; yet, those two words alone alerted me to the power resident—and resonant—in poetry.

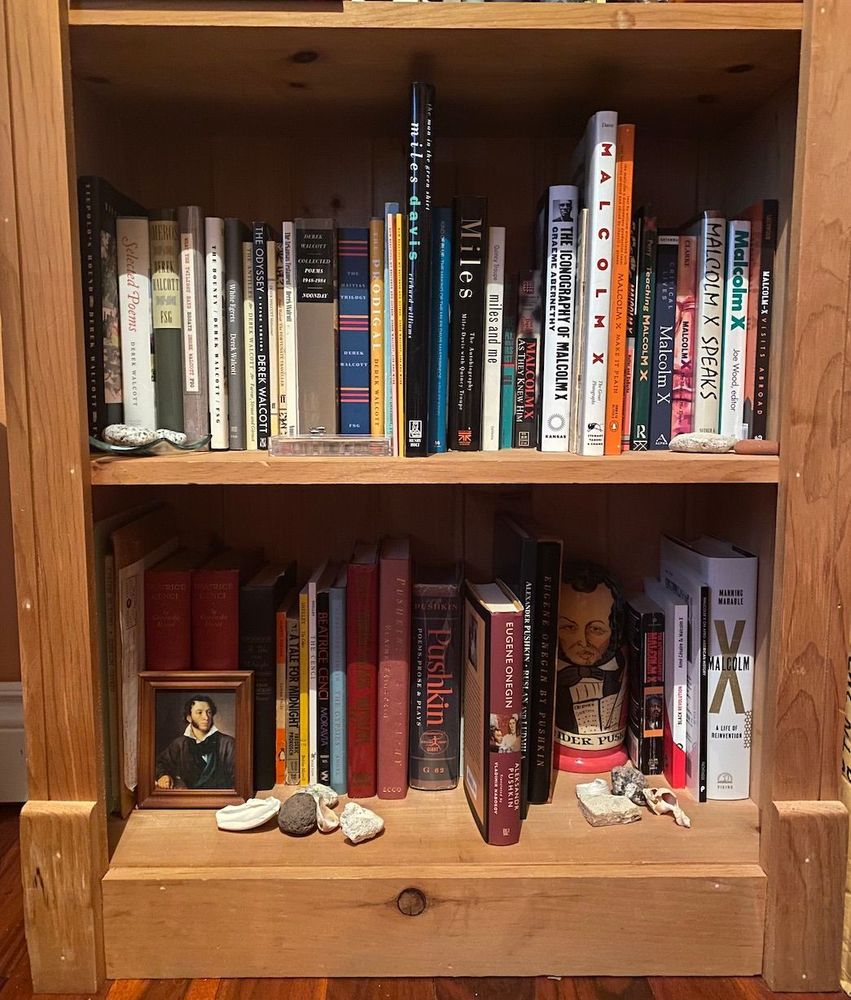

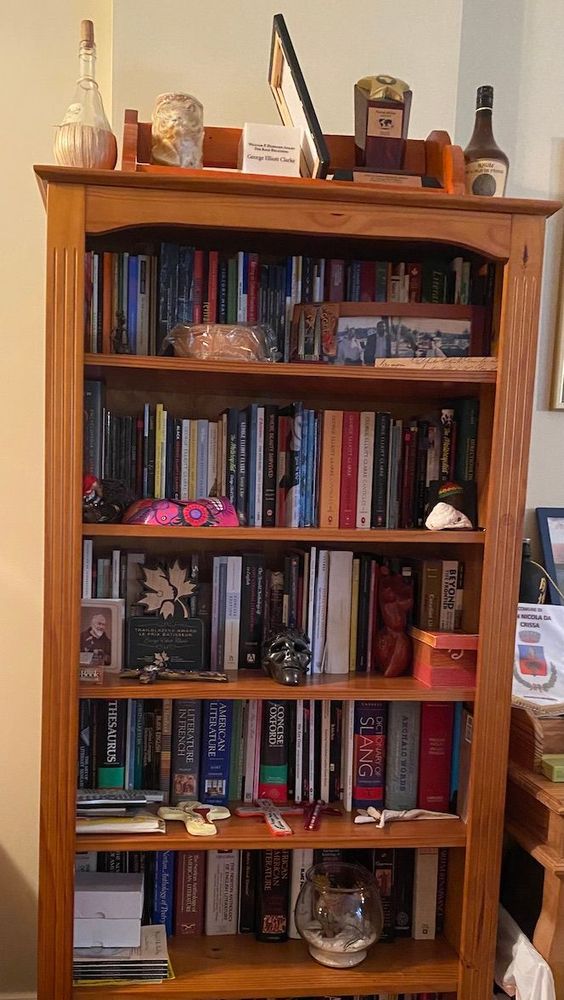

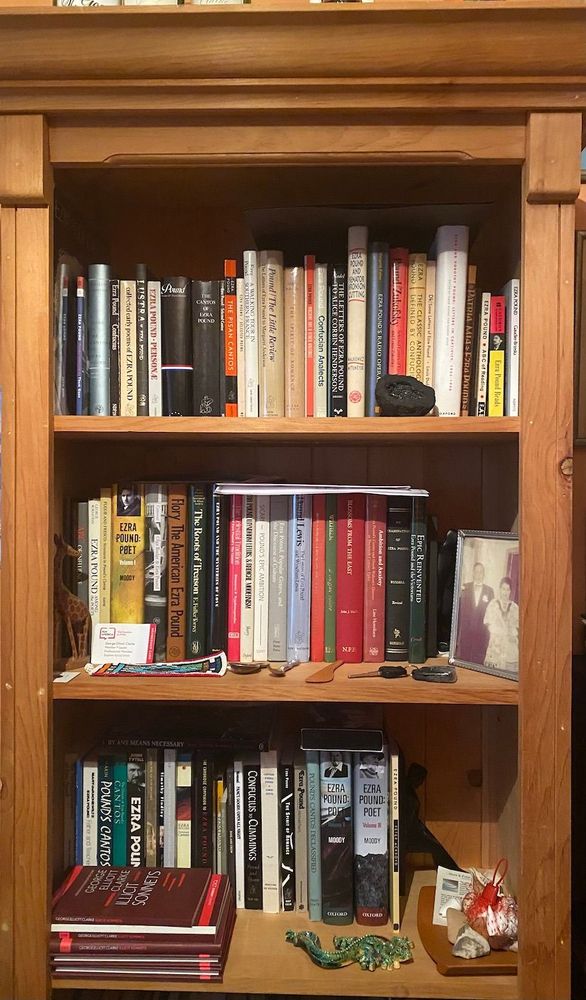

I dwell upon my father’s library (despite my half-sister, upon our father’s death, dispatching boxes of his estate to used book stores; what I have, I rescued) because my own holdings of books is derived from what he treasured—primarily non-fiction or fact-based fiction, with a strong orientation toward (True) Crime, thrillers, political science, history, biography, and journalistic works (such as the chronicle of Indian independence, Freedom at Midnight, by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, 1975). Given this domestic influence, I have—in my University of Toronto office—as much George Grant as is available, along with a shelf of books by and about Pierre Elliott Trudeau (also a hero to my father). My home library is dedicated particularly to shelves (plural) by and about Ezra Pound. Yes, I detest his politics, his anti-Semitism, racism, and affiancing of himself to Italian Fascism. But I try to emulate his reliance on “fact-based” history, on journalism, as well as lyricism, to give us an account of world history, no matter how flawed by bigotry that it is. I think I’m drawn to the “non-fiction” (some of which is nonsense) in the poet—especially in The Cantos (1916-72)—because those were the kinds of texts that my father hallowed (along with The Scofield Reference Bible—1909—which I’ve also inherited). No race nationalist, but rather a liberal who believed that Black people would progress according to our individual talents and merits—plus good grammar and good manners, my father’s ownership of the Cleaver screed contradicted his ownership of the Griffin and Jesse Owens books. Even so, it was by reading those works and Baldwin—and then Malcolm X—that I came to articulate my own sense of African-Nova Scotian (Africadian) racial identity, which is an amalgam of the pride and daring of Cleaver and X, plus the Baptist-based pleas for love that Baldwin articulates. Hence, I dedicate several shelves in my home library to Malcolm X and James Baldwin—but also to jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, and the Afro-Caribbean Nobel Laureate in Literature poet Derek Walcott, for all are symbols of Black Excellence. Yet, I also have shelves dedicated to writings by and about Bob Dylan (my #1 influence as a teen—and continuing) as well as to the great French writer, Violette Leduc. I admire Dylan’s surreal insouciance and/or insouciant surrealism, but also Leduc’s prose that is so purple that it fuses film noir and porno blue. Also, again in fealty to my father’s tastes, I have a bookcase devoted to—ahem—pulse-racing literature, which I am looking forward to donating to the University of Toronto’s Fisher Rare Book Library archives. I believe there is a place and space for playful, sweaty Eros amid all the abstract, intellectual tomes, and I trust that my holdings are suitably imaginative, titillating, provocative, and even well-written: Nabokov and Nin, The Kama Sutra and The Song of Solomon. Certainly, my epic poem, Canticles (2016-2023), published in six volumes, is not shy about chronicling the imbrication of sexual assault with other forms of violence—plus erotic romance—in the prosecution of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and conduct of the hegemony (White Supremacy) established by Europe and its satellites in these 500 years since Columbus—as well as what are manifest in resistance to imperialism and enslavement. As with Pound’s Cantos—as with also my father’s positivist and empirical readings, I insist on documenting historical horrors so as to encourage protest regarding their continuance. As a scholar of African-Canadian literature specifically, my work has been informed by authors that Bill Clarke had in his possession or, I presume, admired: So, I take up George Grant’s Red Tory philosophy, Trudeauvian liberalism, and Saul Alinsky’s radicalism. (My dad was an Alinsky-inspired social worker at the Halifax Neighbourhood Centre in the early 1970s. The then-wife of the HNC director, the American-born Jackie Barkley, met me when I was a boy of 10 at my parents’ dinner-party, but then piled me with gifts of works by Mao and Lenin once she had become a divorced Marxist-Leninist and I was a young “black radical” of 19. These works—especially Mao’s Five Essays on Philosophy —have also been touchstones for me as both scholar and poet.) But I came independently to Malcolm X—and Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon, authors who articulate a powerful politics of decolonization and anti-racism.

The photographs accompanying this essay were taken by Giovanna Riccio, an excellent, truly wondrous poet. They document mainly my de facto shrines to Pound, Walcott, Davis, Pushkin, Malcolm, Dylan. There are also a few pix of a bookshelf that is full of the reading copies of my three-dozen books published since 1983, with 25 of them being poetry works. It is strange to recognize that my own library shelves echo and mirror my father’s book stacks; that I somehow seek to place my own outpourings among those he treasured, or to assemble within my own works his allegiance to JFK (who also “owns” a shelf in my home library—as well as in my office) or to Fleming (who was really a Caribbean writer, given his Jamaican location, post-WW2). Indeed, I published a scholarly essay on Fleming (2014), an opera libretto and play on Pierre Trudeau (2007), and sundry poems on JFK. All of these works—and yet others—have been compelled by my indoctrination in my father’s library. Indeed, if you pick up any of the Canticles volumes, you’ll find that each and every poem concludes with a place-and-date “stamp” representing the site(s) and date(s) of primary composition. I think that device—or affectation (!)—goes back to the Baldwin novels (that always end with a list of the places—cities—of composition, such as Istanbul, Paris, New York, Venice, etc.); or to Pound’s Cantos which range across the atlas and through eras; or to the globetrotting PET and JFK; or to the Bond “epics,” with their peripatetic hero. (Might there be a connection here also between my literary and geographical wanderlust and my romantic odysseys and sojourns with women of various accents and complexions, cultures and continents?)

I’ll end this essay appropriately: With an “Elegy on J.F.K.” Even if “I” am “speaking,” it is with my father’s voice—albeit with the gentle chiding with which an ex-acolyte addresses a disgraced hero.

Elegy on J.F.K.

Death is often spontaneous—

as is dying:

That finale miracle of breath.

And so each of us is severely alone—

as was the jaunty, Finesse king—

the effortless paladin—

Caesar and Caligula as one—

espousing the libido of Lancelot,

the morals of Machiavelli.

His statecraft was helicopter:

to visit among the adoring,

but levitate above foes;

to shuttle from White House

to Ivory Tower

to “black box op,”

a Green Beret in a Harvard robe.

He seemed as limitless as America,

as unlimited as America,

its New Frontiers—evergreen,

ever refreshed,

and yet his stride

has been translated into worms.

De rigueur, but tiresome, Eisenhower was.

His tepid malice dotted the globe

with far-flung missiles, awaiting

commands

to blacken the Red Sea

or redden the Black Sea,

or dirty all the blue water

in the Yellow River.

His U.S.A.—a starry miscreant—

sought to checkmate—

or stalemate—

the East Bloc—

that dishonest region—

and Mao, the Yellow Sovereign.

The Kremlin’s notorious broadcasts—

plus the trial, atomic blasts—

and every shoe banged on every table—

urged on the war plans:

Fallout was stormy impediment

to chats about Peace.

So, by his tenure’s end,

Ike awoke each dawn

to Cuba’s dragnet

arresting U.S. stars—

the glamorous gangsters—

all soon sun-slain,

blacked out,

by spikes of flame,

perforating spy planes

and/or the swamped Contras.

Ike feels that, to face Castro,

is to take a bite of a lemon

and recoil from the sour fangs

of its flavour.

Ditto for Khrushchev:

Neither is indifferent to Intrigue—

these squalid plebeians,

pleased to topple plutocrats,

to exercise predatorial Gaiety.

(Communists prefer boxing,

while capitalists like chess.)

In contrast, come 1960,

spy the Kennedys’ ubiquitous grins:

Jack sports a respectable face

in a clan of ill-repute.

(His smile radiates Wealth,

although, with secret cunning,

his diseases eat up narcotics.

His unregenerate youth requires

burning, scorching medicines.

Unmetrical, his spine hurts him,

but he copes via dismissive opiates.)

He shows an appealing sheen

as he emerges, sun-lit,

from a tyranny of chrome—

happy, proposing new dreams,

new desires, new deeds,

and exuding unbounded thrills—

the call of blithe youth.

His icy marrow allows his unholy poise—

telegenic—

an undwindling efflorescence.

Campaigning for the White House,

tickertape rains down round him,

on that banking avenue,

Wall Street:

showcase of Manhattan’s spectacular patina.

Vigour seems a potential neologism

in his mouth.

He’s left Harvard’s Ivory Tower

to take draughts of Black Tower,

that inexpensive, German white wine.

(His quarrel with Communism is simple:

It’s indigestible—

just sham and pain,

with no room for Champagne.)

His enemies react to him

with feelings as elementary

as Envy.

Inspect his helpmate?

No, ogle his complement—

Jackie, an encyclopedia of perfumes—

opium and opoponax.

A chatelaine of haute couture,

a lovely spirit—

even with her occasional, respectable pout—

her walk is a glide,

and her jiggle—

pleasant disturbance—

is remuage made incarnate—

the motion that stirs a bottle of wine

just before pouring.

The lady appears in the gauze of flashbulb glare

amid vapours of white lilies.

Jackie is pale Luxury in look,

breathy orgasm in voice.

Her delicate luminescence

mirrors a Playboy nude

posed personally by Hefner.

Together, Jack and Jackie

are Adam and Eve

as “Beautiful People.”

One anticipates, from their issue,

an assembly-line genealogy

of the Fame-burnished,

the flashbulb-tanned.

She is the rain-pooling Seine;

he is the rain-pooling Charles;

now, both pour as one into the Potomac.

Jack doesn’t want to be pretty,

not only pretty,

puritanically pretty,

but Poetry merged with Power.

Policy is always a visionary opus.

To be the “king” of presidents,

the Churchill of Glamour—

figurative gold mirroring the sun—

and secretly Dionysus—

the darlingest decadent,

akimbo,

demonstrating sculptural promiscuity—

an Apollo,

resident in the White House,

he must stage the new—

the brilliant,

and excite the people with dreams

that make them feel glossy, sleek,

adventurous,

and empowered to dream further.

Thus, even if he fails,

becomes merely frozen opulence,

he still exceeds the caked dirt

of l’ancien regime.

To be “presidential” is to enjoy civilities,

or to open hostilities.

Jack’s sabre-rattling raises up the Berlin Wall,

even as he drops his pants

to fall upon Miss Monroe.

His back, that icy hinge,

feels a reconciling twinge.

(His back brace pictures

an ecstatic straightness.)

The Bay of Pigs—

that lackadaisical massacre—

makes Jack very leery:

The exile Cubans are a bunch

of misfiring desperadoes

(The unimaginative are always

unnecessarily violent.)

Upon this immediate fiasco,

Jack calibrated ill-conceived go-betweens

to arrange affairs—

to fix up trysts

and fix abortions—

involving Mafia gals,

roadside molls,

sidewalk tramps,

anyone who could give a fuck,

but also give a damn

for Secrecy.

Dude was a grisly playboy.

At Berlin, or at Vienna,

Jack could lecture on “abhorrent” combat—

ponder the aberration that is Love—

while rockets leapt up, aerodynamic,

then tumbled back to sea

as rumbling fragments,

or Martin Luther King got caught up

in a whites-only fracas

(white folks arguing over black folks’ liberties),

while those party-barrel drunks—

cracker-barrel Dixiecrats—

nayed and whinnied and boohooed,

and Jack just grinned,

as faithful and as unfaithful to Ideals

as is perfume to a body.

(NATO is the miraculous, luxurious Atlantic,

plus the English Channel, the Mediterranean,

the Hellespont, and the Baltic.)

But elsewhere a coup was let to fester,

damning Vietnam’s Diem

to eventual chilling on ice,

his generals letting him petrify

in derisive silence: Quickly,

Violence quaked Vietnam—

“Republic” and “Democratic”—

in an ascending pyramid

of downward spiralling bombs.

On Friday, November 22, 1963,

Jack arrives—

a medicinal character—

to make peace among Texas hombres.

He descends with a braced back,

but nixes the limo’s bubble-top.

He knows he’s a choice magnet for bullets,

but doesn’t make a big deal of it,

though Dallas toasts blue-collar rednecks.

He bears palpable culpability for the death of Diem,

but smiles gaily.

And why not?

Jackie escorts him with violent decency—

her rose or lilac aura—

the pink skirt and jacket, immaculate

(soon to be sequin’d with blood).

Paired, but peerless,

they cruise into the fanatical jostling

that’s Dealey Plaza,

looking as unbroken as sunlight in a forest,

and as rich as the sun.

Jack is at the minute

of immortality—

the minutiae of immortality—

oblivious to volatile animus.

Oswald, the demonic hero—

invariably subversive—

exits his Dallas “digs”

with a 6.5 mm Carcano Manlicher rifle

(hid in a sack that once held curtain rods).

A Marine marksman and curious Marxist—

maybe merely an eccentric rube

or “patsy” of some monster of Intrigue,

or just an estranged hubby,

out to win back the regard of his wife—

Marina—

and feeling cynically rueful—

takes up his place—

or role—

in a sniper’s nest.

That rifle is a twitchy instrument,

but Oswald forges electricity at high noon:

Lightning shoots down from his library.

Out the Italian gun, fire gleams.

Oswald is crouched over the grand blanco

from on high;

he’s eyed backra—

would-be killer of Fidel—

eyed him like a one-eyed lover,

squinting.

The reports give wondrous echoes:

Pigeons flap skyward on ribbons of wind.

Beauty is halted.

Oswald spies, in the limo,

a visceral gargoyle—

not some unsuspecting saint like Gandhi—

and sees the golden lad flinch

as the second shot gives the Prez

a disastrous jolt

in shadow-garbled sunlight.

As he lurches progressively,

a bull’s-eye bullet hits

amid a crossfire of cries and cheers,

distressing the Caesarian head,

so the brain flies apart

in erratic spray,

and dreams fall bluntly black.

The brain matter forms a gelid aurora—

or penumbra;

blood becomes a damp accessory,

as exasperating wounds open wide

and News suppurates.

Oswald feels ugly joy in squeezing off

“impossible” shots,

then scrambling, haphazardly, penniless,

his own breath jarring his lungs,

and Camelot becomes a crime scene.

The T.V. shows Jackie’s bloodied glory

as black-and-white makeup.

Then, Oswald is alive, just to feed

T.V.’s voracious affliction—

the assassination of a president—

an acceptable Putsch.

But Jack Ruby strolls into the Dallas police—

or T.V.—station.

He looks shudderingly respectable.

(But the lowdown is, he’s pretty low-down;

on the up-and-up, he’s a so-and-so;

and scruffy.)

He’s perfect for eyeglass-factory tabloids—

and now fires on Oswald,

who feels, instantly,

his belly’s chief collapse.

He must end up maggot-chewed,

grub-diddled.

Gone his recoiling breath,

Oswald joins J.F.K.

as figures in hospital beds—

as fictitious corpses.

Both are now a package of cadavers.

But look at Oswald’s ugly flowers—

as opposed to Kennedy’s heroic tomb,

an ethereal flame at the end.

Oswald’s corpse raises hungry worms.

(His internment was as feeble

as the funeral for a saint.)

In the gilt, northern backwoods, autumnal,

with ruddy undertones,

some sea salt bracing the air,

I awoke,

to the revelation

of Death,

that an elegant life—

a man who had known Poetry

as an old-fashioned weapon—

was now but newsprint.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Clarke, George Elliott. “My Autobiography Is Just a Bibliographical Appendix to my Father’s Library.” Shelf Portraits, 24 March, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/my-autobiography-is-just-a-bibliographical-appendix-to-my-fathers-library. Accessed 7 August, 2025.

APA

Clarke, George Elliott. (2023, March 24). My Autobiography Is Just a Bibliographical Appendix to my Father’s Library. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/my-autobiography-is-just-a-bibliographical-appendix-to-my-fathers-library

Chicago

Clarke, G. “My Autobiography Is Just a Bibliographical Appendix to my Father’s Library.” Shelf Portraits, 24 March, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/my-autobiography-is-just-a-bibliographical-appendix-to-my-fathers-library.

George Elliott Clarke

Born in 1960 in Windsor, Nova Scotia, on the Avon River, George Elliott Clarke is one of Canada’s finest writers and educators. By his own admission a poet first and foremost, Clarke works additionally as a playwright, novelist, literary critic, and professor at the University of Toronto, where he was appointed as the first E.J Pratt Professor of Canadian Literature. He has also taught at Duke University, McGill, the University of British Columbia, and Harvard. As a teacher, Clarke’s scholarship centres on African-Canadian literature; as a writer, his work amplifies what he terms “Blackened English,” paying homage to the cadence and language of Clarke’s upbringing in African-Nova Scotian communities.

Since winning first prize in the Writer’s Federation of Nova Scotia’s provincial poetry competition at age twenty-one, Clarke’s publications and accolades have not ceased; his work spans twenty-five poetry “works,” two novels, six dramas and, true to his intermedial approach to language, three libretti. Clarke has additionally edited and authored several academic collections, and his work foregrounding the African-Canadian experience made him the subject of the 2012 anthology Africadian Atlantic: Essays on George Elliott Clarke. Clarke was Toronto’s Poet Laureate from 2012-2015, and Canada’s Parliamentary Poet Laureate from 2016-2017. His awards and accolades, while too numerous to list in their entirety, include the Governor-General’s Award for Poetry (2001), the National Magazine Gold Medal for Poetry (2001), the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Achievement Award (2004), the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Fellowship Prize (2005-08), the Dartmouth Book Award for Fiction (2006), the Eric Hoffer Book Award for Poetry (2009) and the Queen Eizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal (2012). Clarke is additionally the recipient of eight honorary doctorates. He currently resides in Toronto, and is online at https://www.georgeelliottclarke.net.

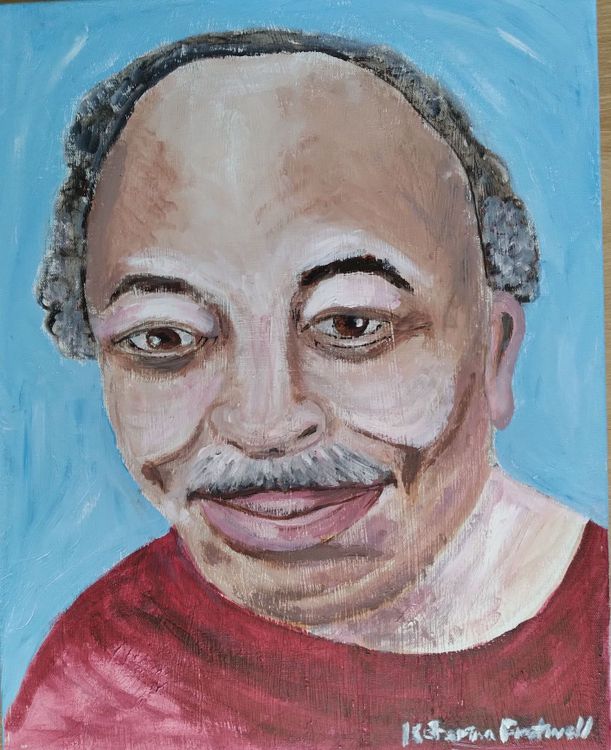

The author’s inadvertently Shakespearean portrait is by Katerina Fretwell, and is appropriately titled “Larger Than Life.”