[…]. It is not the first time

I have tried to give up some words. Everyone eventually does

no matter how carefully preserved and through

how many inconvenient moves, but one cannot be responsible

for the words forever.

—Monty Reid, “Burning the Back Issues”

I am thinking here of my library as a site of ongoing choice. Yes, the choice of what to read today and tomorrow, but also of what comes in and, perhaps more interestingly, of what goes out. It isn’t loss exactly, though there is at times a degree of mourning involved, but rather the deliberate act of culling that is a necessary element of building and maintaining most personal libraries. A library is always a question of space, of priority, of what justifications we have—conscious or not, reasonable or not—for the books we choose to keep.

I grew up in a house full of books. My dad is a remarkable book collector. There was a steady stream of books arriving in the mail, complemented by weekend trips to bookstores (squeezed in around escorting his kids to practices and rehearsals and friends’ houses). I remember shelves gradually filling more and more corners of the house, and the ongoing battle against the entropy of it all. I remember helping to shelve and re-shelve, to move entire bookcases and components of the collection. Today we call his library and mine our “joint holdings,” a kind of dispersed library that despite the combined shelf space sees us both discard books regularly by necessity.

There is greed early on when building a personal library (at least there was for me). When you set yourself free in bookstores for the first time, or library sales, or book fairs, and can make choices secure in the knowledge that shelf space is ample, filling that space in is a joyfully indiscriminate act. When you’re young and buy a bookcase, it is all potential—it is there to be filled because it is empty. Today, somewhat less young, a shelf is bought to relieve pressure. The books are there already, and it isn’t possible to ever get ahead of the problem.

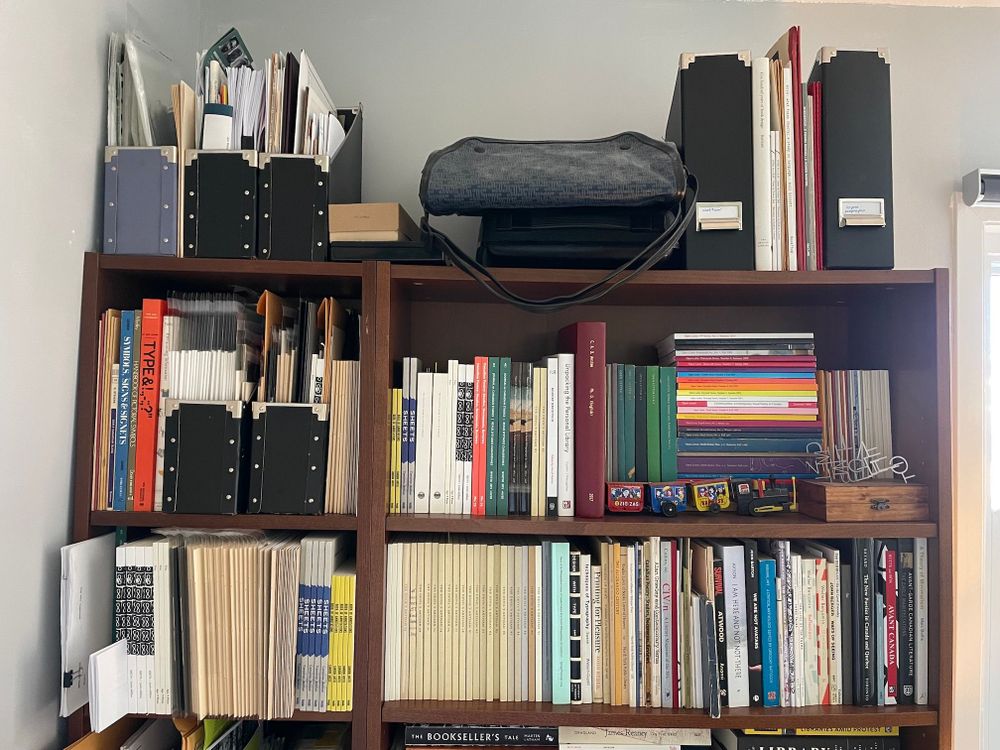

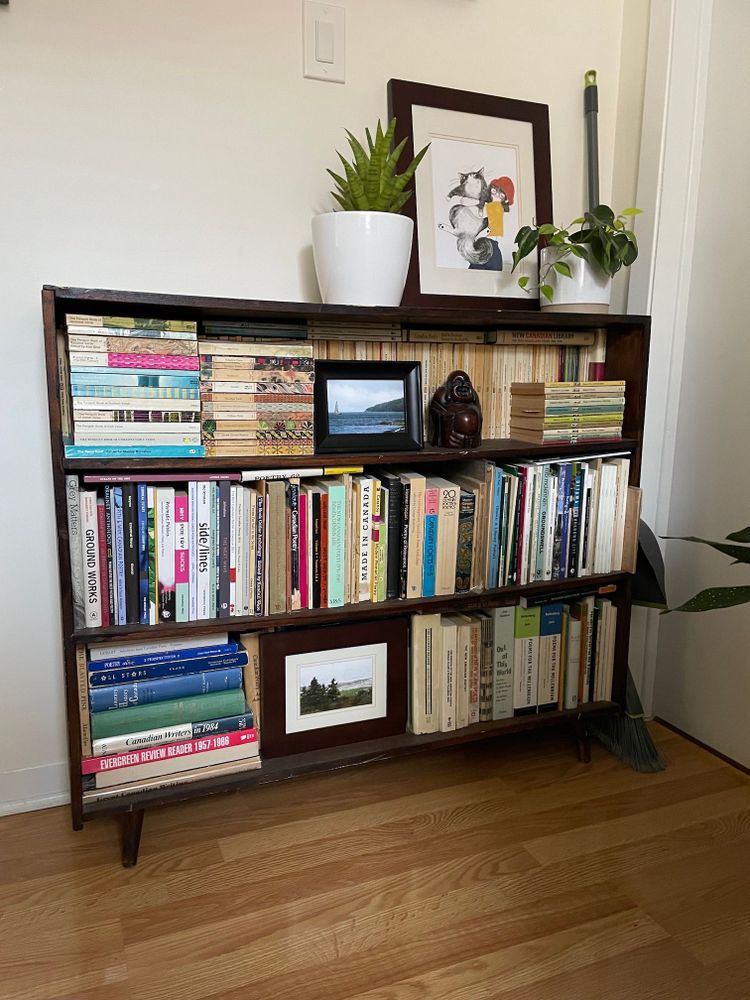

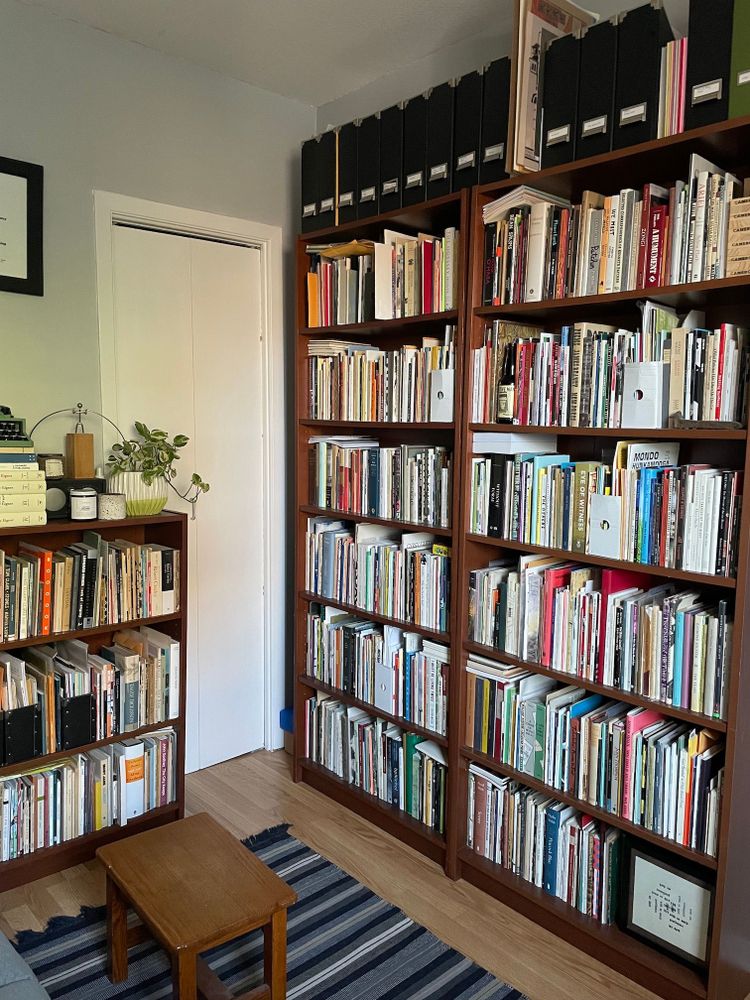

In my home, poetry is confined to the library upstairs. Currently the room holds three standard tall bookcases, two short ones, and an additional tall skinny one. There is a desk near the window, while the longest wall is occupied by a small sofa and works of art (among them two prized Nil Press poster poems from the 1960s by William Hawkins, a hand-stamped Nelson Ball broadside, and a sheet of marbled paper from a workshop my partner and I took). In total, there are some 22 shelves for poetry, a further 5 or 6 committed to criticism and memoirs and the books from my past life in academia that have survived previous culls, and a few pockets dedicated to publications I’ve had a hand in. (Ok, some poetry spills out into the hallway, but those are mostly anthologies and don’t count in quite the same way).

I think there is value in having only this limited space. If I had more space, I would just fill it. Like a lane added to a highway, it wouldn’t solve the problem of congestion. I have limited bookshelves, as I have limited hours and mental bandwidth. It simply reminds me of the choices I’m already making—what to read, what to read again, what to seek out more of, and what to put aside.

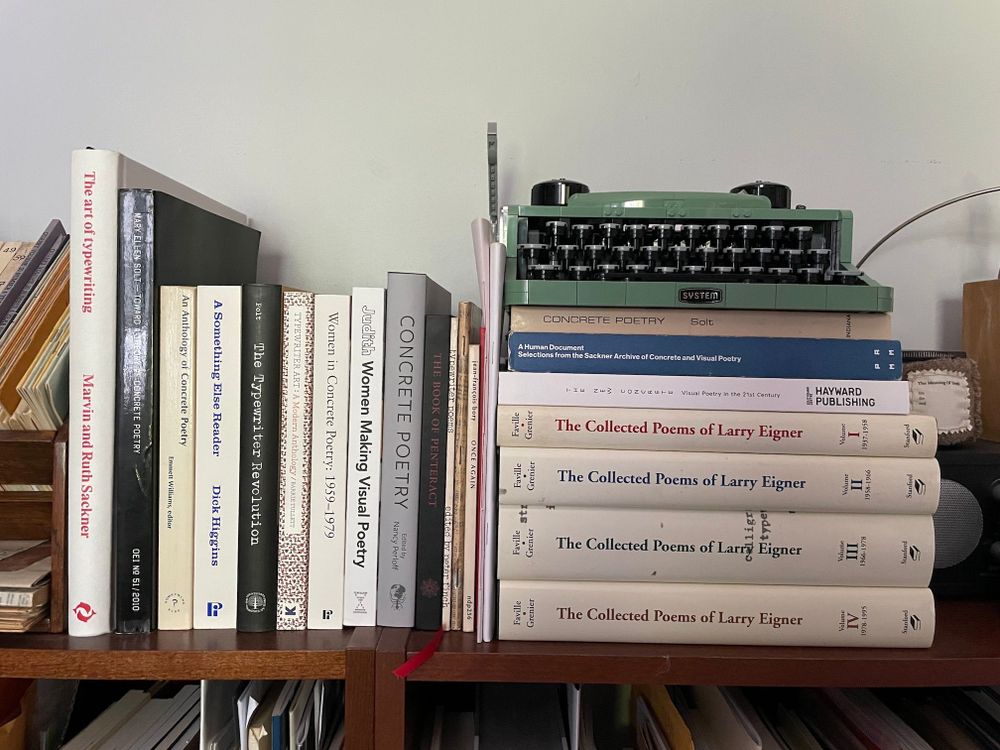

The library at any time reflects a balance of my immediate interests (minimalism, typewriter and concrete work, certain writers) and my long-standing ones (Canadian small press history generally, certain presses and editors, some strains of critical writing). Trade books line the main shelves, while chapbooks are housed in magazine holders on the tops of the bookcases (when the volume of chapbooks by a given poet reaches critical mass, it is moved onto the main shelves—my Nelson Ball books are flanked on either side by boxes of his chapbooks, for example). Two typewriters—one owned by William Hawkins, and one by my father-in-law—sit beside boxes of Weed/Flower, Seripress, and presspresspress publications on top of one bookcase. The oversized four-volume Collected Poems of Larry Eigner has no choice but to be horizontal on top of another, settled alongside anthologies of concrete poetry. A small crate of records sits on the floor in front of binders full of bookseller catalogues hanging around from my dissertation. Personal objects line the shelves as well—a childhood wind-up train from my grandmother’s house, a “sensitive man” beer bottle from a visit to the Al Purdy A-Frame, a print of some Phyllis Webb lines from Naked Poems done by my partner during a letterpress lesson she arranged for my birthday.

But after thirteen years with roughly the same physical space for the poetry, it has exceeded capacity once or twice over, and so today as books come in, books must go out. I cull for necessity and make decisions for different reasons. Perhaps my tastes have changed, or the book doesn’t feel like it would warrant a re-read, or it is today of a lower priority than another book on the same shelf (acknowledging the contingency of all such prioritizations), or I have a friend I think would appreciate the book more than I do. Of course, each decision may also be a mistake.

I’ve developed a faulty practice, but it at least gives some structure to all of this. Culled books move first to a corner in the room, and later to a set of boxes in the basement, where from time to time I sort into other categories: books to save for “someday” when I have more space (when will that be?); books to give to friends; books to donate to sales; books to sell. By the front door, there is a box of books for little free libraries, and these days I try to take a handful on neighbourhood walks to send back into the world.

I find both liberation and guilt in culling. The fresh air of a shelf that has space is a relief (not clear space mind you, but rather just enough space to add a book without having to work too hard), but there is also a feeling of failed obligation to the writer culled. What will I regret discarding, perhaps enough to buy again someday? What will I forget I ever owned?

Nonetheless, these culled titles go back into the literary ecosystem, as they all will someday, for someone else to find and struggle with. Any used book you have ever owned was once in someone else’s personal library. The prize you found was either culled by another or held onto until the day they died, at which point the person tasked with dealing with their library opted to let it go. Culling is a vital mode by which books circulate and re-circulate, and so it is worth remembering that, perhaps mercifully, books are in our orbits—or more accurately we are in the orbits of books—only briefly.

Cameron Anstee

May 2023

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Anstee, Cameron. “On Culling.” Shelf Portraits, 17 November, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/on-culling. Accessed 6 March, 2026.

APA

Anstee, Cameron. (2023, November 17). On Culling. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/on-culling

Chicago

Anstee, C. “On Culling.” Shelf Portraits, 17 November, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/on-culling.

Cameron Anstee

Cameron Anstee is the author of two collections of poetry—Sheets: Typewriter Works (Invisible Publishing, 2022) and Book of Annotations (Invisible Publishing, 2018)—and the editor of The Collected Poems of William Hawkins (Chaudiere Books, 2015). He is the editor and publisher of Apt. 9 Press and holds a Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Ottawa.