The year I finished high school, my father’s closest friend and colleague, George Galbraith, retired, after having taught English at Sir Charles Tupper Secondary School in East Vancouver since the school opened just short of three decades earlier. My dad taught Chemistry, about which I had to admit I wasn’t passionate. George’s children, well into adulthood, weren’t much for reading. He asked if I’d like his library.

I’d always been a reader, and had wanted to be a writer since childhood, but during my teen years most of my writing was to pen-pals, and I spent more hours watching MuchMusic and listening to “alternative” CDs than I did in the literary realm. Then, the summer before my last year of high school, the pen-pal with whom I exchanged the most intense and epic letters had quoted a few lines by Sylvia Plath. On our next family road trip, I’d cleared out the Plath section of Powell’s Books in Portland. I didn’t go as far as to measure how many centimetres these books occupied on my shelf, but I counted them frequently, a new gardener tending seedlings.

I also plundered the poetry section of the local public library. In The Faber Book of Contemporary Irish Poetry, I found Seamus Heaney’s “Personal Helicon”: “I rhyme / To see myself; to set the darkness echoing.” In his seeing himself, I saw myself.

A few months before graduation, I won first prize in a local writing contest – for a sonnet, no less. A cousin gave me my own copy of the Irish anthology as a graduation gift. My parents gave me another Faber find, The Rattle Bag, Ted Hughes’ anthology of poems for young people, though as I read through the pages I sensed I was already growing beyond them.

One long June evening, George showed up with the books, yellowed and dusty, in yellowed and dusty boxes. For decades, he’d kept these books in his classroom for reference. They smelled long-shut. I don’t remember much, other than feeling exhilarated and unworthy; I thanked him abundantly, he wished me well and left. A man of words, yes, but a select few, for a select few.

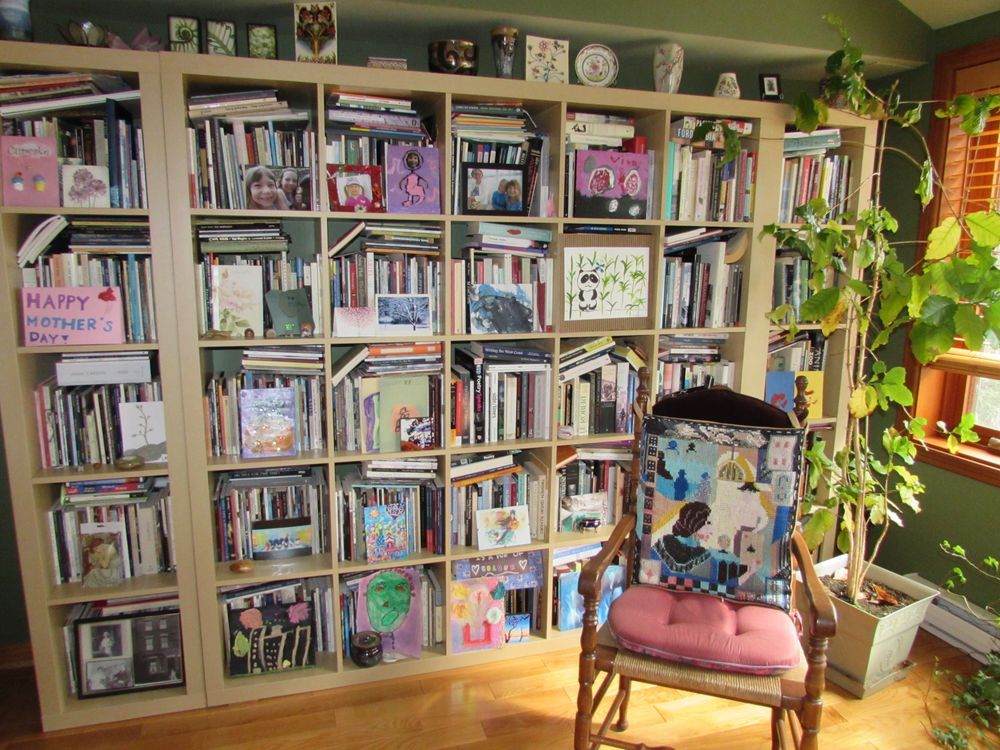

Now I didn’t just have some books, I had a library. It wasn’t vast, but that I owned books I might not get around to reading was a thrilling novelty. Here were the classics I’d been studying in my English Literature 12 course: Beowulf, some Shakespeare plays, the Romantic poets, the collected Hopkins, a massive Norton with Bible paper. There were also works of criticism, which felt particularly adult. My parents had invited me to cull, but I wanted everything, even the Milton. Weekly, I dusted my shelves. Nightly, I wrote my thousand words.

I couldn’t imagine having too many books. Turning away from stacks of freebies in the hallways of the English Department I would teach in. Failing to keep my promise to myself that once all my shelves were filled, I would not start laying books horizontally across the vertical spines, would not start shelving double-depth.

In time – through moves from Burnaby to Vancouver, Vancouver to Québec, then Ottawa, then Montréal – George’s library dissolved into what became my own. And when my own exceeded its bounds, and again its new bounds, I did, eventually, set aside a few books for the thrift shop. So I’m pretty sure that some of his made their way elsewhere over the years, the pang of parting always acute; the books lingered in closet limbo for months before I finally accepted that they had to go, always with a hope that they would join or begin the library of some other aspiring writer.

A couple of years ago, George stopped driving after one too many mishaps that left him battered and uncertain. His health slipped. He ended up in hospital, at first just for a while, it seemed, until it wasn’t. By the time he died, thirty years after he retired from teaching (the temporal symmetries make his story somehow sadder), his wife, also a family friend, was in a facility for dementia patients. His children didn’t hold a service or publish an obituary. He just vanished.

I’m not sure what became of the poster he’d displayed in his high school classroom, of a cartoon of a chick that cracked its way out of an egg, looked around at the world in bafflement, and went back in. I didn’t know George, really. I knew his voice intoning opinions as I lay in bed those childhood evenings he and his wife came to my parents’ place for dinner. I suspect he was not generous to the most average of his students. He loved The Singing Detective. In later years, he read primarily non-fiction, particularly biographies of American presidents. At the end, he had few visitors and was overmedicated. Reading strained his eyes, but there was CBC radio. For a number of years, he and my father shared a subscription to The New Yorker. When the issues came to me, if I saw he’d marked a piece, I read it.

Would that have surprised him? At a time when I was beginning to find myself, word by word, through the bewildering world, he passed on a legacy I suspect neither of us really understood. Piled in those boxes or stacked on my shelves, the books resembled walls, but what they really were were flagstones or – why not? – yellow bricks. They showed me there was a way.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Bolster, Stephanie. “Portrait of the Library as Obituary.” Shelf Portraits, 3 January, 2022, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/portrait-of-the-library-as-obituary. Accessed 27 June, 2025.

APA

Bolster, Stephanie. (2022, January 3). Portrait of the Library as Obituary. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/portrait-of-the-library-as-obituary

Chicago

Bolster, S. “Portrait of the Library as Obituary.” Shelf Portraits, 3 January, 2022, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/portrait-of-the-library-as-obituary.

Stephanie Bolster

Work from Stephanie Bolster’s current manuscript, Long Exposure, was a finalist for the CBC Poetry Prize in 2012 and 2019; her first book, White Stone: The Alice Poems (Signal Editions/Véhicule Press), received the Governor General’s Award in 1998. She grew up in Burnaby, BC and has taught creative writing at Concordia University in Montreal since 2000.