“Every passion borders on the chaotic”—Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking my Library”

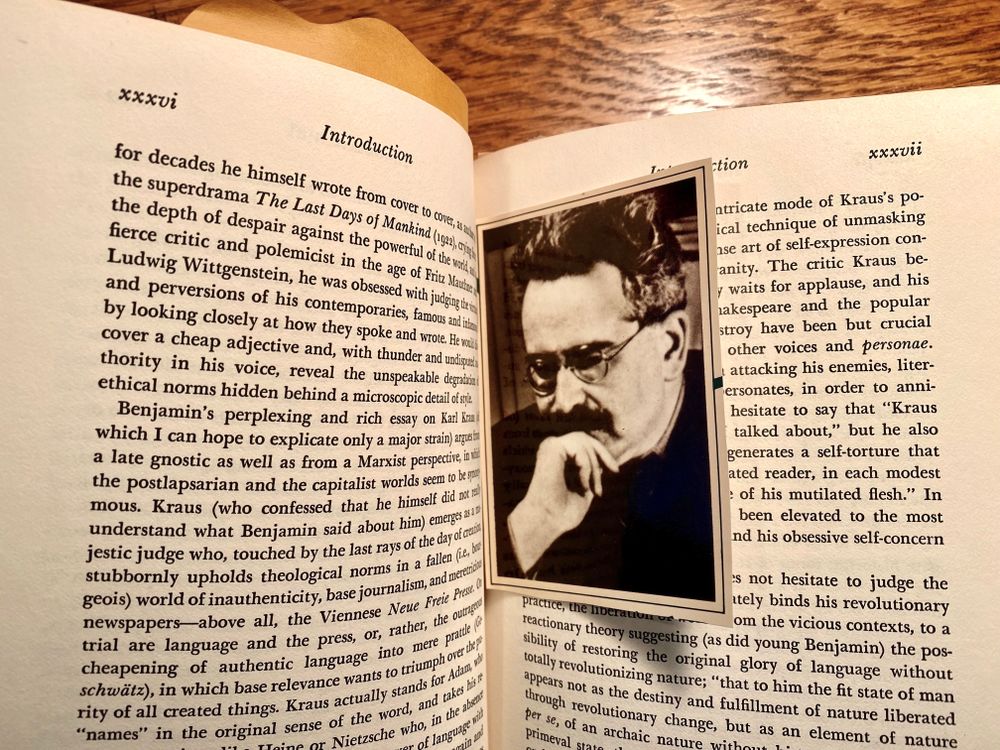

In this small library I sit amongst someone else’s books. Of course almost all books are someone else’s books, and any collection a collection of what others have composed (although Walter Benjamin suggested that “of all the ways of acquiring books, writing them oneself is regarded as the most praiseworthy method”). But this feels different: specifically, these are all books that had belonged to poet Robin Blaser, his signature inscribed in each flyleaf. They bear other markers of his reading: small and faint pencil ticks in margins, slips of paper marking pages to return to, notes scrawled in a small hand on some of those scraps of paper. Dust jackets have been dismembered so that a cut gatefold bio, author photo or back cover book synopsis is now tucked decoratively inside a cover, outsides turned into insides. I feel like an archival thief, or scholarly scofflaw, sitting here in secret, reading the dead poet’s books, following a method of Susan Howe’s, “through words of others”—tracking Blaser’s mind and eyes, as it were, as they scanned these pages for the memorable, trying to re-member his rememberings.

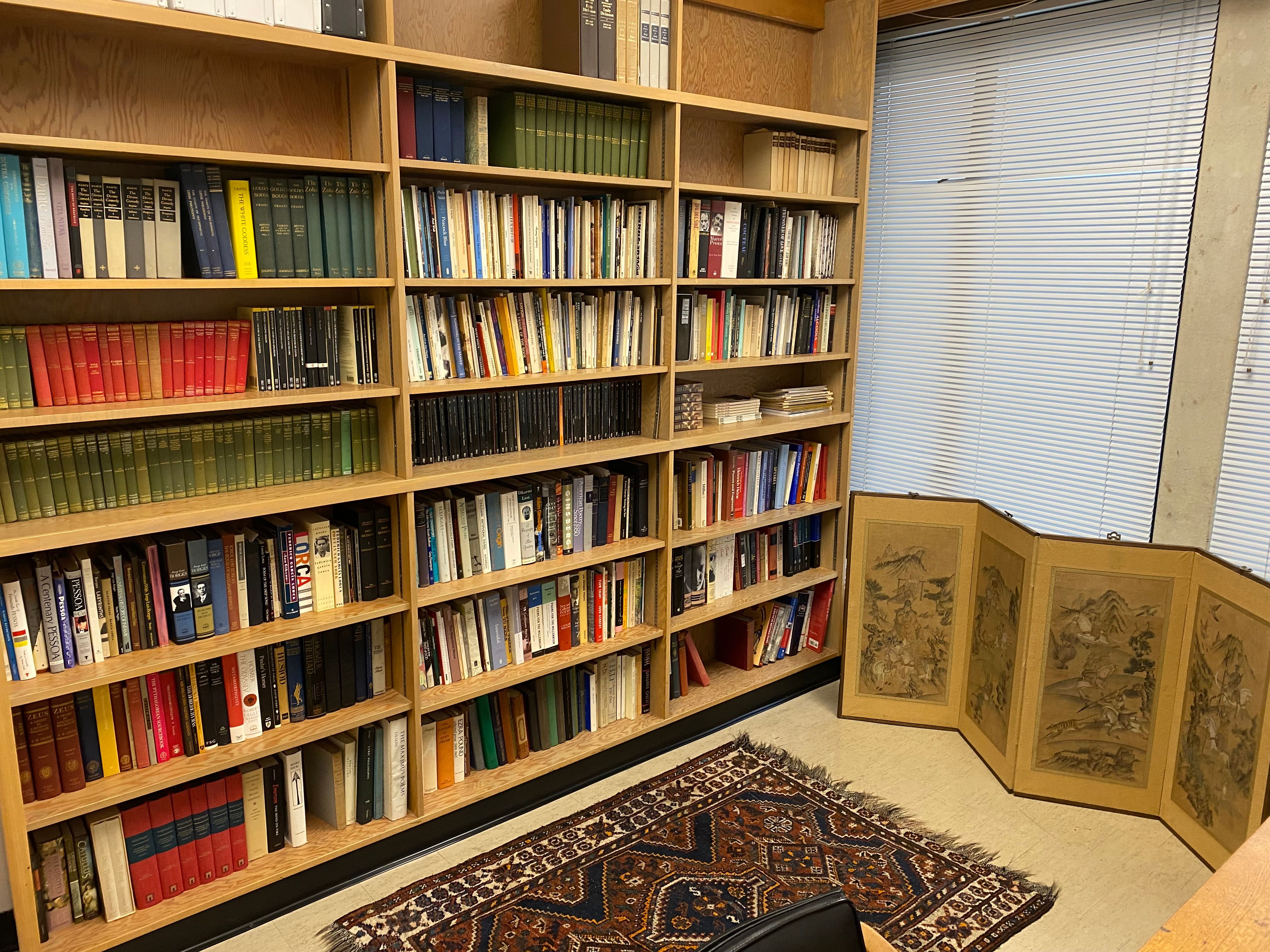

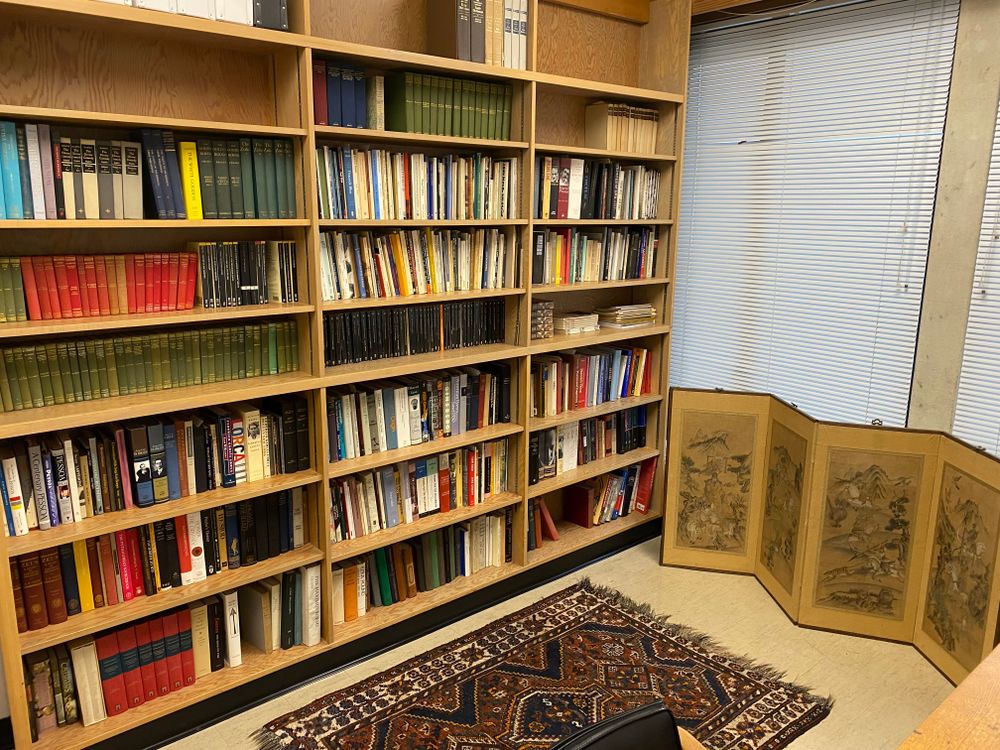

Blaser died in 2009, at the age of 84. His partner David Farwell kept Blaser’s remarkable study intact in their Kitsilano home until his own death in 2020, at which point it was donated to Simon Fraser University, where I work. There were many thousands of books in the house, 360 boxes in fact were packed up and delivered to the university, where they soon took over a large sorting room in the Bennett Library, the librarians anxious to disperse them as quickly as possible. I had an idea: convert an empty English Department office into a commemorative Blaser Study, complete with his oak desk, art deco lamps, wool rug and a few hundred of his books. I had to act quickly, picking volumes on instinct and intuition—books I knew or suspected were important to the composition of Blaser’s life-long poem, The Holy Forest. The trails of that magic wood were blazed all through these volumes—but I could only glean so much, limited as I was by time and space. I felt like I was rescuing a scant few volumes from a shipwreck, before the storm and sea took the rest. I could not afford to be methodical.

I grabbed everything Dante that I could. Multi-volume sets (which I personally own very few of) were an attraction, so there is a five-volume set of The Zohar, Whitman’s Notebooks & Unpublished Prose (six volumes), sets of Emerson’s, Melville’s, and Dickinson’s works, as well as fourteen volumes of The Hogarth Press run of Virginia Woolf’s Complete Works, and twelve volumes of the Bollingen Series Complete Works of Paul Valéy—and a near-complete set of Loeb Classics. There are books by modernist predecessors (a large number of H.D, and Gertrude Stein, which I could not resist), and many of his New American—and Canadian—contemporaries. French and German literature is plentiful—betraying some of my own biases no doubt (it is a pure pleasure to sit in a room well stocked with multiple volumes by Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Proust, Jabès, Rilke, Hölderlin, etc.). There are also numerous books of theory, Blaser being the sort of poet likely to drop a lengthy quotation from Giorgio Agamben or Hannah Arendt into the middle of a poem.

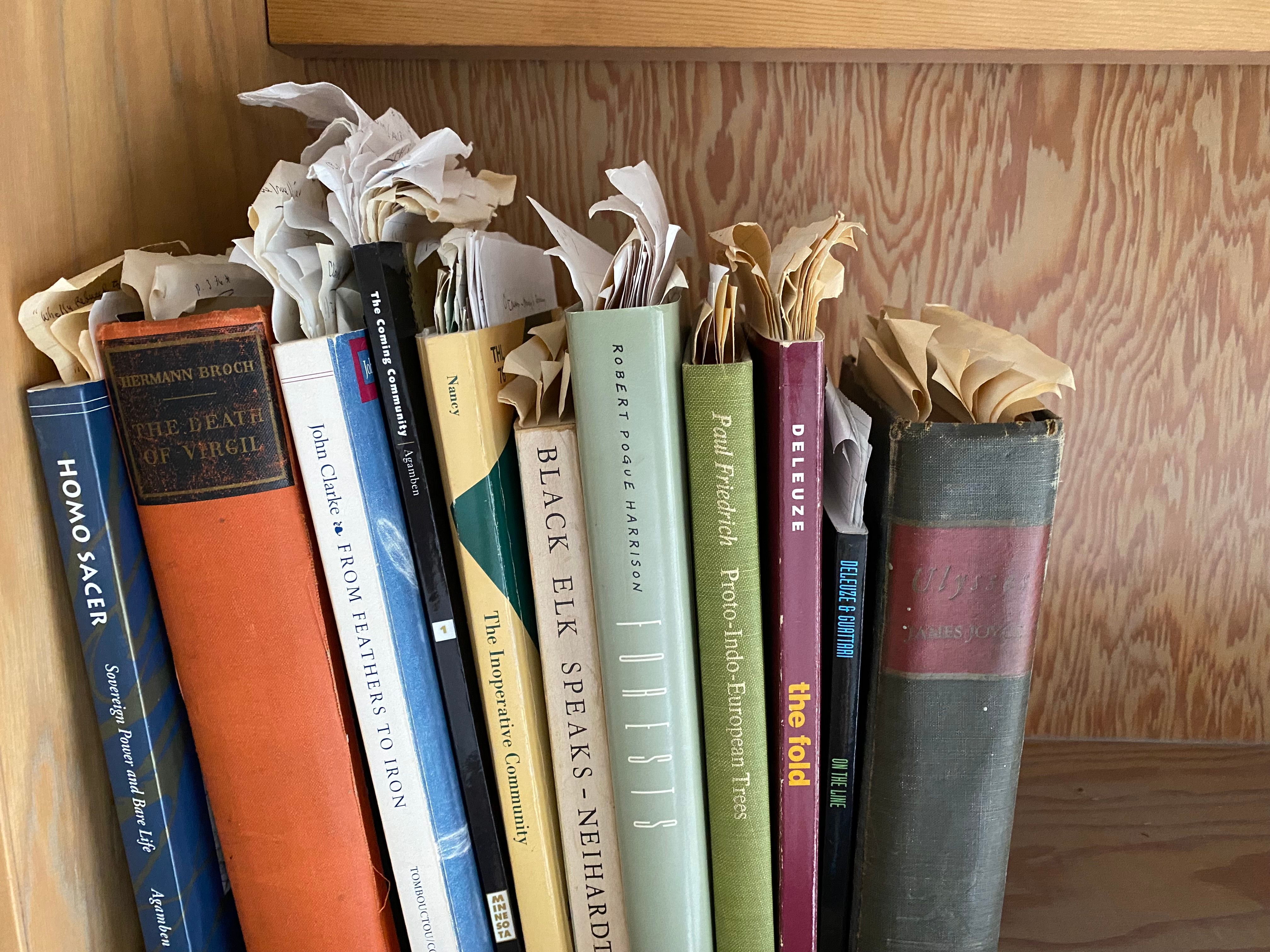

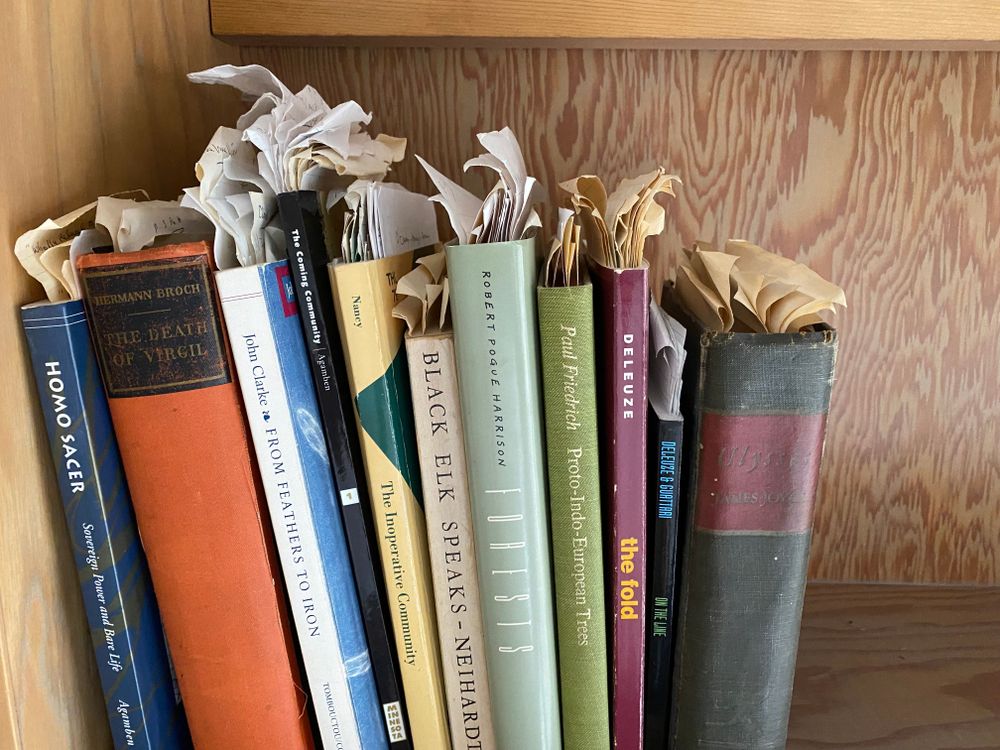

I have yet to organize the books, but that will come. For now I am enjoying their randomness and disorders. My own books sit in associative clusters between which I am always shuffling volumes, trying to see what might appear by association, and that is where things yet stand with this small Blaser collection. “Chaos is not chaotic,” Edouard Glissant reminds us in Poetics of Relation. Chaos, in fact, is relational. I place together a seemingly random set of books notable for the sheer number of paper slips Blaser left between their pages, the tops of the papers jutting up and curling over, shaggy and yellowed like the bent tops of ripe barley. Late twentieth century theory (Agamben, Nancy, Deleuze) rubs shoulders with modernist classics (Herman Broch’s Death of Virgil and Joyce’s Ulysses—both books of which Blaser had numerous duplicate copies), John Clarke’s uncategorizable From Feathers to Iron, two books on trees (Robert Pogue Harrison’s Forests: The Shadow of Civilization and Paul Friedrich’s Proto-Indo-European Trees), and John Neihardt’s Black Elk Speaks. What relations might be tugged from these dense books over which then poet clearly poured? Perhaps I will find the time to work that out.

In this small library, this accident and fragment, I let Blaser’s reading lead me to a poem—“Blazing Space” within which I can think again. While unplanned, this became a necessary act of restoration in the wake of the deaths of poet elders, Phyllis Webb, Lee Maracle, and Etel Adnan, passing within days of each other, just as an atmospheric river arrived out of the Pacific on a dark November weekend and I shelved volumes that had once belonged to another lost and beloved elder. The small Blaser library became a refuge—and a place to write. This space I am trying to blaze is entirely relational; it entangles insides with outsides—so Webb and Maracle and Adnan, the latter two outsiders to this fragment of Blaser’s library, come into the writing—as do the disasters of the climate crisis rattling the windows of this Burnaby Mountain office. As does Edouard Glissant—also not present here on these shelves, but a welcome infolding for a decidedly Eurocentric library, heavy with western classics and modernist experiments.

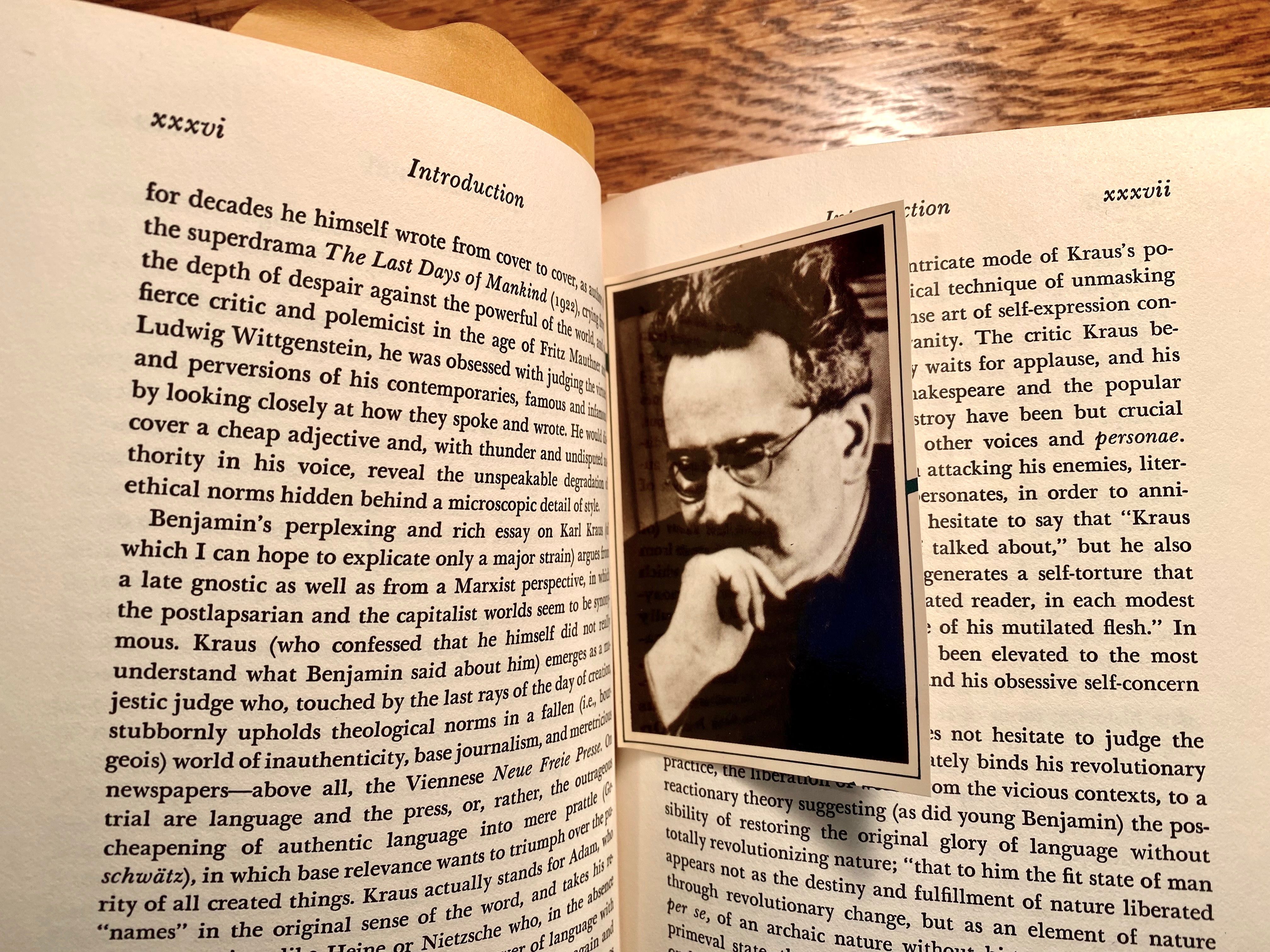

I take up Blaser’s edition of Walter Benjamin’s Reflections, and leaf through Peter Demetz’s introduction. Blaser has left behind several pencil marks and paper slips, and on a page marked by a cut-out of Benjamin’s author photo I read: “But by quoting again and again (a device that Benjamin himself liked), [Karl] Kraus restores the original purity of the word by lifting it out of its undignified context and by pushing it back towards its origins”—and I see a restorative method. My poem grows relationally, from quotation to quotation, from passage to passage that Blaser marked, from a practiced outside I cannot keep out of this small literary space, however sheltered it feels at times. There are five “movements” in the poem now—the fifth, here, humming with Benjamin and Glissant—amongst others.

BLAZING SPACE: FIFTH MOVEMENT

1

Between the books on the shelves

and the branchings of our minds

a raven not a crow

scale and relations

and the deeper echoes of ruins

everyone with a language take one step forward

and the entire forest takes

one step forward

and so Macbeth etc.

the raven circling the forest it can’t see

for the books on the shelves I am reading

upsetting its cousins the crows below

out damned spot

I love you too much

little cousin little relation out out

fold yourself back into the relentless dark

of the ache of the ark

~

As above / so below

stars you cast magic across

ceiling blue or down into dark water’s phosphorus glow

looking for the ones with the slowest revolutions

and most entanglements

the one we can never be finished with

because everything is alive

everything cohering / refracting

feet on the ground

head in the sky

above and below

both word and act

entangling

2

In flight from

what I cannot

contain or curtail

periphery to periphery

errant and meandering

soluble tones sung

from the forests within

the accumulation of sediments

and just outside the door

the whorls of time—

by constantly moving

one can gather stones

and weave the material of the universe

~

Traveller, what really are your reasons?

We broke the world and

we still don’t know who we are

or that we are not separate from it

or anything else we can see or read or love

rivers of persons

constellations burrowed into any night’s sky

3

There is a messenger

who rushes towards us

full of fire and flood

a book of quotations

/ a library of books

lightning’s zigzag course burning

the word and the world’s vivid lining

turned inside out

stirring the air

the mountain spewing fire

and the fight we have inadvertently joined

against the creaturely world

reverberating shatteringly from the abyss

the sea weeping at our graves

and the school anthologies cast open to receive us

~

Someone sent word

that before Arras

on the last blasted tree

a lark began to sing

in the vacuum of shells

and so became a quotation

in the book of the world

and the world of the book

4

Baroque: when you are all out of Monet

to quote a word is to call it by its name

the glorious medium of being

where a plant speaks in the idiom of its fragrance

quotation a restoration of the word

by lifting it from unspecified context

and returning it to the forest

where it is gathered in the particularity of things

sword fern sitka spruce huckleberry and bryophytes

cosmic energy / vivid and hidden intertwinings

the veil covertly woven

over our immersion in a world of things

~

Chaos is not chaotic

revolutions of planets do not stop

or end in any meaningful duration

somewhere we

rhizome into fragile connection

drawn in the swirl

that which we are or might be

senses assumes opens

gathers scatters continues

and transforms turbulence

5

I read inside the study

its nomadic ground shifting

circa all times at once

then go out into burnt and

rain-lashed lands

over which certain birds

ravens or maybe crows

still circle through wilderness

and pang certain words

keep coming back to

migratory mind

~

A world teeming with resemblances

things and their signs

emblazoning one another

refractive and intra-active

the Holy Forest

on these mundane shelves

and spreading over ghost mountain sides

the book a flutter of wings

in the underbrush giving me

these entangled reconfigurations

of the inside and out

the word ‘reality’ is also a word

and we are a small part of

what we are trying to understand

this ongoing performance of the world

the trees in last night’s wind

a baroque rerouting

through these measured disorders

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Collis, Stephen. “Relational Space: Unpacking Robin Blaser's Library.” Shelf Portraits, 17 February, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/relational-space-unpacking-robin-blasers-library. Accessed 4 March, 2026.

APA

Collis, Stephen. (2023, February 17). Relational Space: Unpacking Robin Blaser's Library. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/relational-space-unpacking-robin-blasers-library

Chicago

Collis, S. “Relational Space: Unpacking Robin Blaser's Library.” Shelf Portraits, 17 February, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/relational-space-unpacking-robin-blasers-library.

Stephen Collis

Stephen Collis is the author of a dozen books of poetry and prose, including The Commons (2008), the BC Book Prize winning On the Material (2010), Once in Blockadia (2016), and Almost Islands: Phyllis Webb and the Pursuit of the Unwritten (2018)—all published by Talonbooks. A History of the Theories of Rain (2021) was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for poetry, and in 2019, Collis was the recipient of the Writers’ Trust of Canada Latner Poetry Prize. He lives near Vancouver, on unceded Coast Salish Territory, and teaches poetry and poetics at Simon Fraser University.