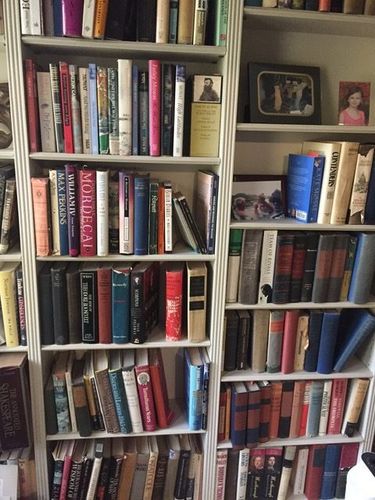

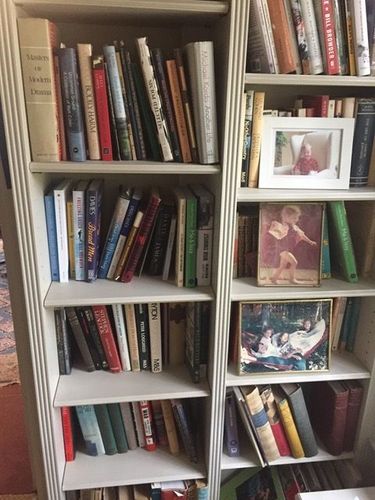

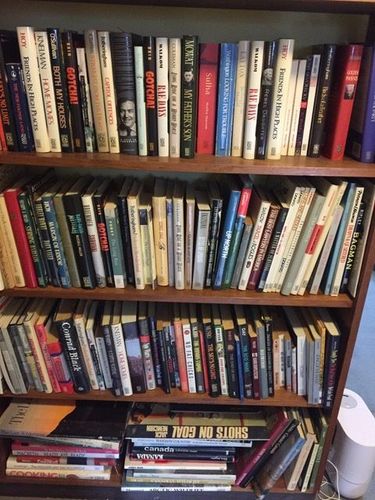

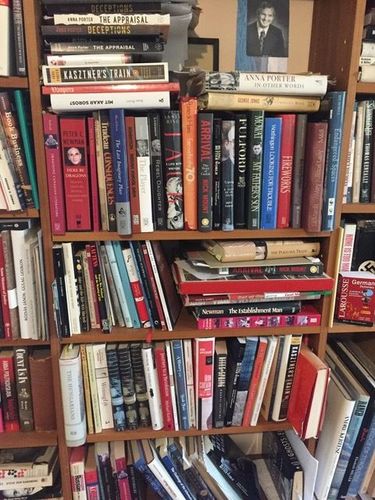

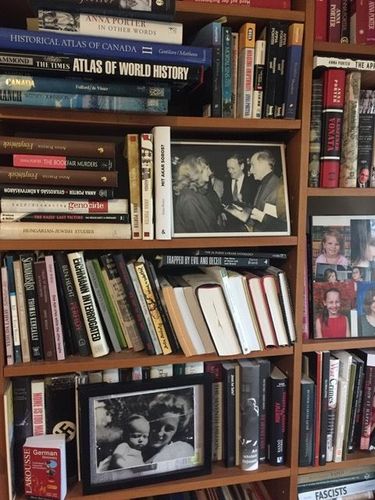

I live in a library. It masquerades as a house but its every wall and most corners are occupied by bookcases groaning under too many books. The shelves are packed tight and extra books lie on top of the ones standing upright. While there is not much of a system, I tend to know where to search for a book I happen to need at a particular moment. For example, I was recently asked about Sandor Marai’s Embers. Marai was a celebrated Hungarian author and I had loved this book and still think of it sometimes. That means it could have been in my study, close to George Jonas’s Beethoven’s Mask, because George had also loved Marai. I had published George’s Beethoven’s Mask and I remembered thinking those two books would be happy together. But it’s not where it was, so I searched the shelves just outside my study where I have kept some of the books I had worked on or published. It’s where Irving Layton, Al Purdy, a couple of Sylvia Frasers, Dalton Camp and a whole lot of Farley Mowats live. Some of Margaret Atwood’s books are here, The Edible Woman (we had met over that manuscript), Dancing Girls, but many more are in the bedroom and in the living room.

I finally located Embers on one of the shelves where I had put my mother’s favorite books after she died. She had introduced me to Marai when I was ten. That’s why I had first read him in Hungarian. Embers now is sharing space with Muriel Spark, Graham Green, Thomas Mann and volumes of Hungarian poetry, including some she could still recite even after her ninetieth birthday.

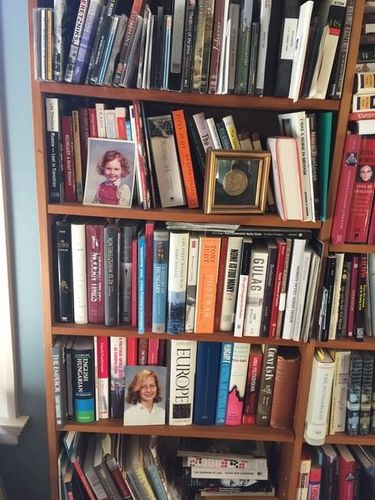

I have kept a lot of books about history in my study. Tony Judt; Timothy Snyder; Anne Applebaum; Timothy Garton Ash; and books about Poles, Czechs, Hungarians and Slovaks. I had read most of these when I was writing The Ghosts of Europe, but I still go back to them. Recently, I had reread Anna Politovskaya’s Nothing But the Truth. She had been murdered for writing about Russian state corruption. Her book is endorsed by Salman Rushdie, whose words have also meant a death sentence that he has, so far, miraculously evaded. I have recently reread his Midnight’s Children. It used to be next to Proust with the classics, but after the recent attack on Salman at Chautauqua, I have pulled it out and put it next to my bed. It is a delight to read his inventive, lyrical language and reacquaint myself with his quirky, entirely credible characters.

I have a lot of dense histories and personal memoirs about the Holocaust in Hungary. Some of these, the most tragic, most immediate, the angriest are in Hungarian. They are a terrible reminder that those humorous, light-hearted, story-book heroes of my childhood had also been capable of the atrocities that sent hundreds of thousands of their fellow Hungarians—men, women and children—to the gas chambers. I also go back to these every time there is another attack on Rezso Kasztner, the central figure in my book, Kasztner’s Train.

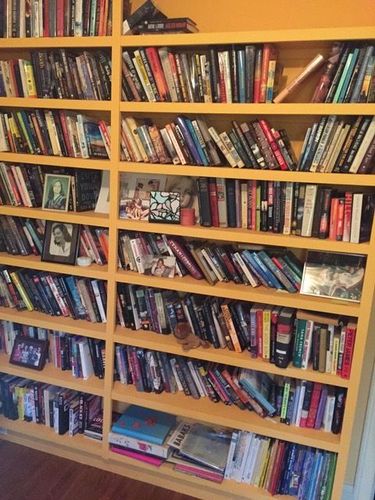

In what used to be my youngest daughter’s room there is an entire wall of mysteries of all kinds: police procedurals, cozies, noir, private detective, etc. I am particularly fond of mysteries where women are not dismembered, stabbed multiple times, bludgeoned, or otherwise gruesomely murdered. I like PD James, Ruth Rendall, Tana French, Sara Paretsky, Kate Atkinson, but I have also loved Peter May’s Lewis Trilogy, and Ian Rankin’s Rebus books.

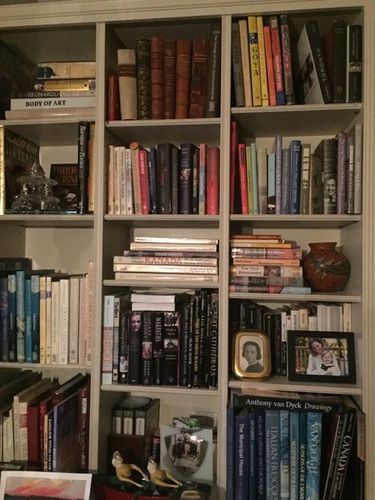

Our bedroom is occupied by an army of classics, art history, actors’ memoirs, and books about the theatre. There is a lot of Shakespeare because my husband, Julian, loves Shakespeare and he is always finding new interpretations of the plays.

There are stacks of books on both sides of the bed—some half-read, some still waiting to be read or reread. My side has Midnight’s Children and Ian McEwan’s Lessons.

The living room is decorated by books on shelves, tables and, usually, the floor. There are various editions (German, Italian, Serbo-Croatian, American) of Bob Fulford and John de Visser’s book Canada: a Celebration, and of Dudley Witney’s great railway books. Julian’s big art books are here: Titian, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Raphael, Michelangelo, Goya, two massive tomes on Delacroix and, of course, Artemisia Gentileschi. Both of Julian’s own books about art you must see are here, as is my book, Deceptions, featuring Artemisia. Abella and Troper’s None is Too Many and Conrad Black’s Life in Progress share a shelf with four books by Alan Fotheringham, Sylvia Fraser’s My Father’s House and Margaret Macmillan’s Paris 1919.

Throughout, there are random photographs of my children, my mother, grandchildren, and Julian. They are not in any particular order, it’s just where I had put them when I found them. One of these days, I am going to sort out the photographs and organize the books, so I won’t have to search everywhere for a book I happen to need at the time I need it. But I would miss the sense of adventure a disorganized library provides. There is always something I haven’t opened for a long time, a discovery.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Porter, Anna. “Shelf Portrait: Anna Porter.” Shelf Portraits, 7 March, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-anna-porter. Accessed 10 March, 2026.

APA

Porter, Anna. (2023, March 7). Shelf Portrait: Anna Porter. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-anna-porter

Chicago

Porter, A. “Shelf Portrait: Anna Porter.” Shelf Portraits, 7 March, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-anna-porter.

Anna Porter

Anna Porter is the award-winning author of twelve books, both fiction and non-fiction, most recently, Deceptions, a novel, and In Other Words, a memoir. Other books include Kasztner’s Train, Ghosts of Europe and Buying a Better World, George Soros and Billionaire Philanthropy. Gull Island, a psychological thriller, is her twelfth book. She co-founded Key Porter Books, an influential publishing house she ran for more than twenty years. She also writes book reviews, profiles, opinion pieces, and stuff about Central Europe. She is an Officer of the Order of Canada and has received the Order of Ontario.

Author photo by Mark Raynes Roberts.