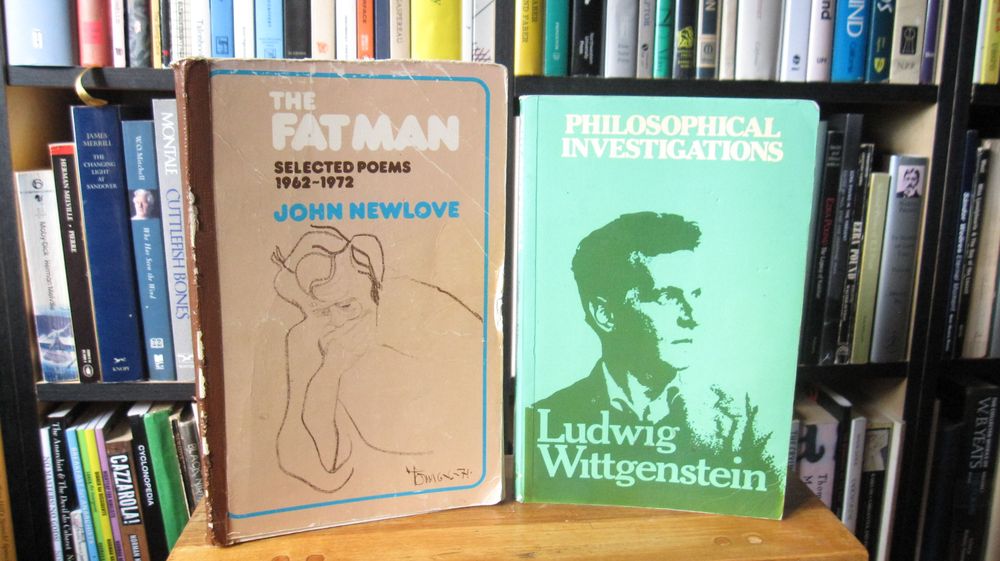

I HAVE WRITTEN DOWN ALL THESE THOUGHTS AS REMARKS… These words not only preface this Shelf Portrait but one of the “first” books in my present library, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations,[1] "one of the first,” because Wittgenstein’s “Private Language Argument” (sections 243 ff.) was the topic of my philosophy Honours paper, and the book was one of those that made it to Montreal with me when I moved from Regina after completing my B.A. at the U of R in 1986.

In another, perhaps more important, way, the “first” book in my library, “first” in the sense that the ruler of an ancient polis was the archon (the “first”) or one word for ‘prince’ in German is der Fürst, is John Newlove’s The Fatman: Selected Poems 1962-1972.[2] When I first met Newlove during his stint as the Regina Public Library’s writer-in-residence, I mentioned I didn’t know his work: he bent under his desk, hauled up a box, and handed me this copy of The Fatman. That afternoon, reading it in the shade on the white picnic table on the patio in our backyard [I] thought “I can do that!” and wrote my first three poems.

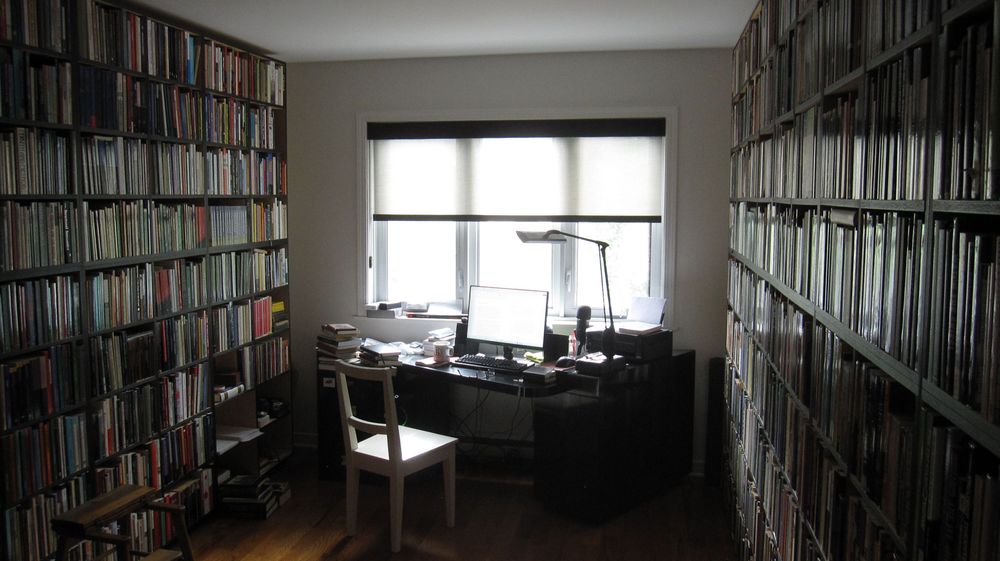

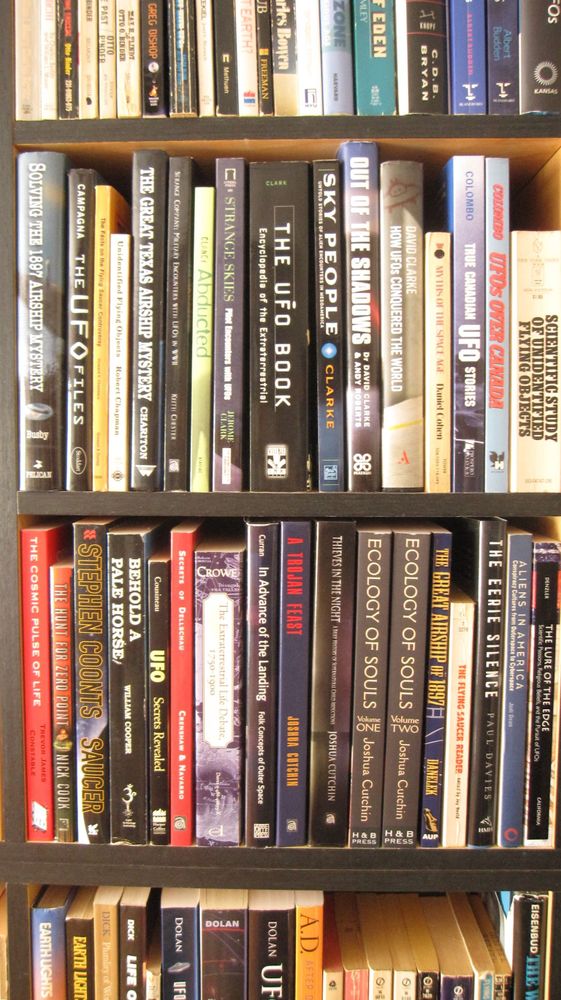

These two books, one philosophy, the other, poetry, are emblematic of my intellectual and creative trajectory. Following the more-or-less ironic example of one of my teachers, my library is organized into Wahrheit (truth) and Dichtung (poetry). When I sit at my desk, to my left are the shelves holding philosophy and theory (Adorno to Zupančič), philosophy and (primarily) literary theory anthologies, German Romanticism, Marxism, ecosocialism and ecological studies, psychoanalysis (Freud, Jung, Reich, and Lacan), history, Indigenous studies, reference, and German language and literature; on my right, poetry and fiction (A.E. to Zwicky), literary anthologies and periodicals, classics, Medieval romances and folktales, mythology, anthropology and religious studies, psychedelic studies, ufology (!), journals and agendas, and antique books. Oversized books sit on a dedicated shelf behind me.

I’M SKYPING WITH MY FRIEND from Munich, a novelist, editor, erstwhile lawyer, and, like me, a compulsive book buyer. “Is it a disease, a disorder, or…?” he asks.

I offer a number of explanations for our reflexive, obsessive behaviour. First, we’re at a point in our lives where we can afford to buy the books we want, as opposed to all those days as a student or, in my case, precariously employed. Now, we can also make up for lost opportunities, all those books we felt we should have read in our student days or since. As well, we make enthusiastic discoveries, new authors, new fields of knowledge and we, accordingly, go all in: my discovering Andrew Bowie’s From Romanticism to Critical Theory[3] opened up for me the vital tradition that runs from Kant, the German Idealists, and the Jena Romantics to Adorno, the book’s notes and bibliography feeding my list of books I wanted—needed—to acquire. Finally, I paraphrase a most apropos anecdote about Umberto Eco and his legendary library as related by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Eco, Taleb relates, separated

visitors into two categories: those who react with “Wow! Signore, professore dottore Eco, what a library you have! How many of these books have you read?” and the others—a very small minority—who get the point that a private library is not an ego-boosting appendage but a research tool. Read books are far less valuable than unread ones. The library should contain as much of what you don’t know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market allow you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books.

“This is great! I can see all dams breaking now!” he replies…. “I WANT THE BOOKS I READ TO BE MINE.” This sentiment runs counter to my socialist leanings, but the convenience of having the books I want or need to consult, study, or enjoy “ready-to-hand,” unmarked (let alone undamaged) is a great utility and pleasure.My aversion to underlining and marginalia, however, is not absolute. As a teacher and scholar, I’ve learned the value of leaving a trace of my studies on the page: close readings and complex analyses need be charted. But, there is a value, too, in rereading a book sans those traces of earlier study, so, in some cases, with closely-studied volumes, I’ll have both a working and clean, reading copy.

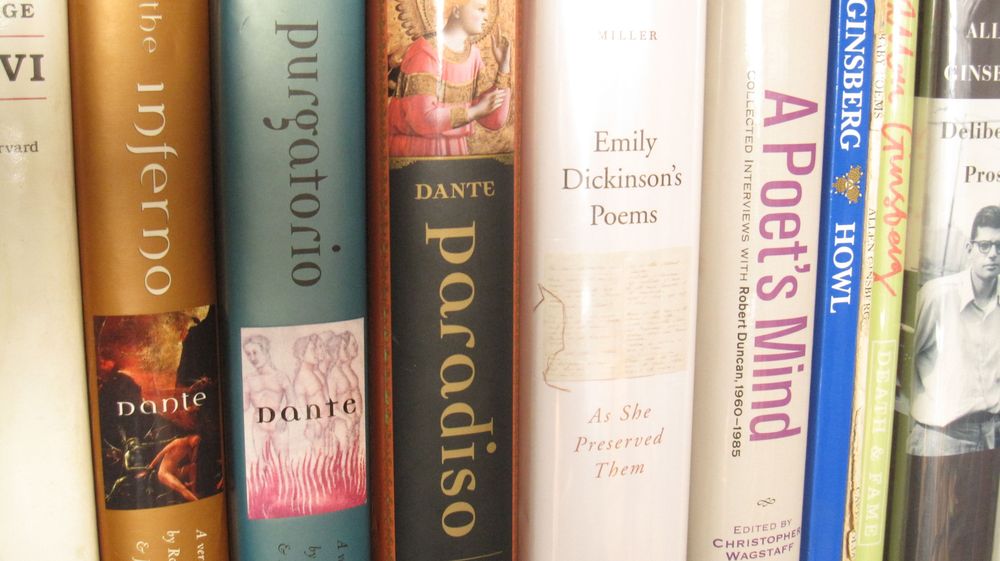

MY BOOK COLLECTION IS A MIX of memory, utility, and obsession. Books, like any object, can hold sentimental value: the edition of The Fatman Newlove gave me that started my writing poetry; or an old anthology of Victorian poetry,[4] gifted me by my brother-in-law, whose vivid biographies of the poets so much enlivened a period of intense engagement with the Pre-Raphaelite and Decadent “Yellow ‘Nineties” poets; or that number of Conjunctions (33) wherein I discovered the works of Peter Dale Scott and Yoko Tawada. A growing number of the library’s “holdings” are archival: correspondence and memorabilia (including the poster for the launch of my first book), volumes by poet friends, periodicals with the first appearance of their poems, even one friend’s literary remains…. My favourite poets are bookish. Coming of age when I did, T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land was required, unquestionably canonical reading. As fate would have it, the first poet I picked from the Regina Public Library’s shelves after my poetic interests were piqued by Newlove’s gift was Ezra Pound, whose Cantos (which I studied in grad school), pioneered (among other things) the early Twentieth Century’s collage poetics. The work of Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, John Cage, Susan Howe, and Kamau Brathwaite, among so many others, also came to hold a place among my models and influences. Every Easter, I studiously read through Dante’s Commedia. As a university student during the Theory Wars, I witnessed the ways a poorly-grasped notion of “intertextuality” was used to drub a no better understood idea of Romantic “genius:” however impoverished this effective history, it, too, at the time and for a while afterwards, oriented my poetics. As a result, my writing practice is as much reflexively as reflectively “palimpsestic” (as the volume by Gérard Genette on the Wahrheit shelves, Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree[5] would have it), as much reading, if not moreso, my poems consciously and conscientiously “a disturbance of words within words”[6] (despite subsequent—and ongoing!—engagements with the more thoroughgoing philosophies of language, protosemiotics, and poetics bequeathed by the Jena Romantics). And there has always been a drive to completeness. Enrolled in a summer course in the literature of the Beat Generation, not only did I obtain every book on the reading list, but every book by every author on that list, along with important, ancillary volumes, such as Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry[7] and its companion The Poetics of the New American Poetry[8]. Teaching “literary criticism” (theory) prompted me to reread what I’d studied during my student days (and more!), resulting in my, over time, acquiring a fairly extensive literary theory collection, from Matthew Arnold on down. To this day, I watch for each new volume in the Stanford University Press edition of The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche or for an opportunity to get another in The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant.

MY LIBRARY has been, arguably, a lifelong project. It begins with books from the public library. My dad would haul piles to the checkout desk, history (usually military), space, dinosaurs… “Are those all for him?!” the librarian would ask.

Of course, my own “personal library” had some private holdings, too. What at the time were called “comic books” (war, horror, science fiction…) and a few books gifted young, young me; I still have the edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales[9] from the wife of my father’s high school teacher, the woman who set my parents up on a blind date. Over time, as my allowance grew and I earned some money of my own, that library expanded to include paperbacks, again, mainly science fiction and fantasy and military history. As my interest in particular series of these books waned, I’d donate them to the public library.

Already in high school volumes of poetry (Newlove, Suknaski, Szumigalski, others I forget now…) and philosophy (Kierkegaard, Sartre, Wittgenstein…) start to fill the shelves in my bedroom. By the time I’m in my undergraduate studies, I’m buying books other than those required for my courses from the university bookstore and ordering in volumes to complement those from a local, independent small bookstore. Volumes of literary theory (I still have well-known volumes by Jonathan Culler and Derrida’s earliest books) find their place on my precariously wobbly shelves. After completing my undergraduate degree, I relocate to Montreal, shipping my “small” library—twelve? twenty?—liquor store boxes.

In Montreal, I discover used books, and the library begins a slow swell toward its present form. Fiscal constraints, however, restrain my buying even all the discounted used and remaindered books I’d like and sometimes necessitate my selling some of these same books back. After graduation, I relocate back to Regina to work at Grain magazine, shipping the now even-larger library. Nine months later, I pack it all up again and return to Montreal with a friend in his white pick up. In Montreal, the library returns to growing slowly. I move it three times before more or less settling down into one apartment in 1999. Twenty years later I schlep over 2,000 books to a new, larger apartment two blocks east where I finally secure for myself and the library a study. As of this writing the large, south-facing double bedroom houses more than 2,700 books. Seven more are on order, not including the four ordered today….

ONLY BOOKS? It’s a strange, stunted poet whose ear isn’t attuned to music, lyric and absolute, whose hand isn’t moved by rhythm. (It is, after all, the rhythm of the voices that intrude, muffled, into the womb that is our first lesson in the mother tongue.) And how important music has been for philosophers, from Pythagoras and Plato, down to Nietzsche and Adorno! Doesn’t my “personal library,” then, include LPs, tape cassettes, CDs, and music files, not only of music, but poets reading?

Like pretty much any North American adolescent of my generation, I started a small record collection in high school, which grew and expanded to include various genres and media over the years. Acquisitions were inspired not only by shared tastes (certain songs were required listening at gatherings of my tight circle of friends) but by “research.” I borrowed recordings of poets from the university library and made cassette copies of those that seemed most important to me; I recorded interviews with writers and their readings from the radio. These cassettes became what I called my “Poetry Archive Project” (PAP). Among these, it was a recording of Yeats reciting “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” that opened my ear and understanding to prosody’s essential relation to melody and tune. That one summer’s “Beat Immersion Course” included a deep dive into jazz and Bebop. In the 2000-2001 academic year, I took part in a teacher exchange, spending these two semesters at Marianopolis Cegep. Having nothing to lose (were they going to fire me?), I came up with a number of new courses, one, “Poetry from Planet Earth,” which used the latest edition of Jerome Rothenberg’s monumental assemblage Technicians of the Sacred[10] as a textbook. I sought out recordings of the book’s “tribal poetries” with which I began each class. Reading John Cage piques a curiosity in his music, along with New Music and its precursors; reading Adorno prompts attending carefully to the music so important to his thinking, especially the Second Viennese School….

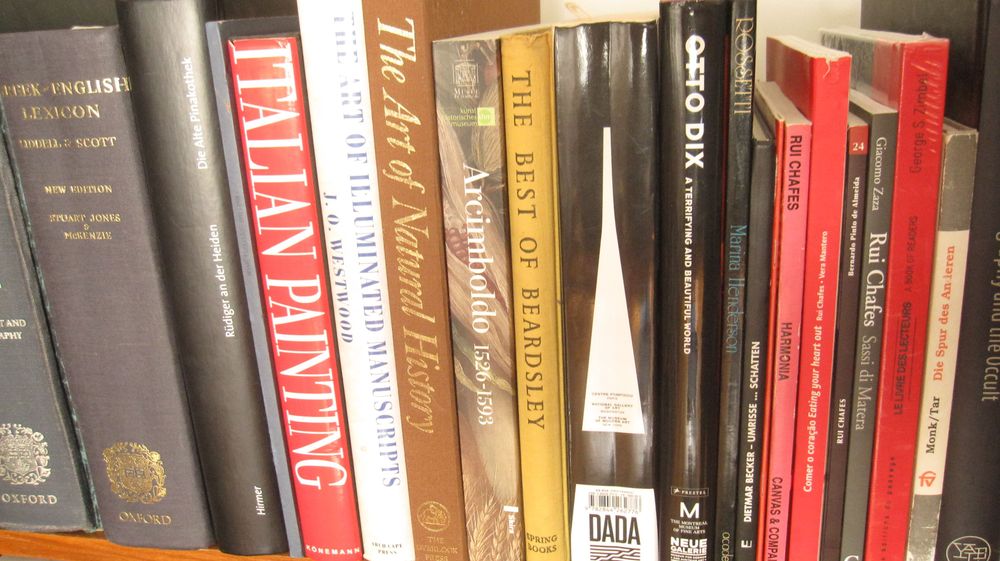

ONLY BOOKS OF WORDS? That interest in late nineteenth-century English poetry also made me seek out a volume of the art of Aubrey Beardsley; friends gifted me a volume of Rossetti’s painting. What attentive study of Futurism and Dada could overlook their multimedia character? What curiosity in German Expressionism could not extend to the art of, e.g., Otto Dix?..

THE LIBRARY IS A TOPOS, in a sense, a timeless one, not only because there clock-time dissolves in the flow of absorbed, attentive reading, thinking, and writing, but also because, as Blake tells us, “The Authors are in Eternity.”[11] On the shelves, A.E. rubs shoulders with Adonis; Emily Dickinson sits between Dante and Robert Duncan. Among all these collected minds, one might be forgiven being reminded of Dante in Limbo, where he sees the great figures of Antiquity, or, for remembering the meeting with la bella scola, the pagan poets of Antiquity, Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan, who, along with Virgil, do the Pilgrim the honour of making him one of their number, “conversing of things here better left unsaid”….

Gallery

References

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983.

Newlove, John. The Fatman: Selected Poems 1962-1972. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1977.

Bowie, Andrew. From Romanticism to Critical Theory. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Poetry of the Victorian Period, ed. George Benjamin Woods, Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, 1930.

Génette, Gérard. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. Trans. Newman and Doubinsky, University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Duncan, Robert. “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow.” The Opening of the Field, New York: Grove Press, 1960.

Allen, Donald. The New American Poetry. New York: Grove Press, 1960.

The Poetics of the New American Poetry. Eds. Donald Allen and Warren Tallman, New York: Grove, 1973.

Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Translated by Mrs. E. V. Lucas, Lucy Crane and Marian Edwards, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, n.d.

Rothenberg, Jerome. Technicians of the Sacred. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blake, William. Letter to Thomas Butts. 6 July 1803. Rpt in Lansverk, Marvin D. L., “Blake’s Letters and Global Exchange,” Lumen, vol. 33, 15 Sept. 2014, pp. 55-86.

How-to-Cite

MLA

Sentes, Bryan. “Shelf Portrait: Bryan Sentes.” Shelf Portraits, 29 September, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-bryan-sentes. Accessed 19 February, 2026.

APA

Sentes, Bryan. (2023, September 29). Shelf Portrait: Bryan Sentes. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-bryan-sentes

Chicago

Sentes, B. “Shelf Portrait: Bryan Sentes.” Shelf Portraits, 29 September, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-bryan-sentes.