We moved to a small house in the woods six years ago, shortly before my wife found out she was pregnant. We’d sort of given up hope of having kids, and in that state, bought a home entirely unsuited for children. Though I guess that’s not entirely true—it’s beautiful out here; our property sits on a half-acre of Oregon wildwood, the sort of place a kid can flood with the magic of exploring. But all the hidden creeks and bramble thickets in the world don’t change the fact that the house we bought when we thought it would just be the two of us has turned, a half-decade and two kids later, into something utterly chaotic.

This is an essay about my bookshelves.

I should say I’ve seen what it looks like when people keep books properly. Years ago, shortly after I sold my first novel, my publisher, the legendary Sonny Mehta, invited me to his house for dinner. It was one of those incredibly Central Park places where the elevator opens directly into the apartment because each floor is essentially just one apartment. I rode up, nervous as hell, an inadequate bottle of red wine in hand, and as soon as the elevator doors opened I saw the beginnings of a wall-to-wall-to-wall (as in, floor-to-ceiling as well as from one end of the room to the other) bookshelves. There was something at once unnerving and calming about the sight of so much reading life, immaculately arranged. Although now that I think about it, what was immaculate about the bookshelf was its lack of immaculateness: it was clear these books, which ranged from leather-bound classics to pulp paperbacks and God-knows how many signed first editions from Sonny’s fifty-year publishing career, had been read, placed and re-placed, afforded lives rather than confined simply to scenery. It was beautiful.

I don’t go out much, and I have a real problem with visitor anxiety whenever I find myself in the home of anyone other than my closest friends. But one of the small joys of seeing someone else’s home is the chance to glimpse their reading life, should one exist. I love almost any ordering of books in a home, from the haphazard mess to the pristine, quasi-dictatorial shelf, strictly alphabetical, segregated by genre or format or date. Even those ridiculous color-ordered shelves, where all the red or blue or yellow-cover books exist separately, don’t bother me as much as they seem to bother most people I know. The only time I have a visceral negative reaction to someone’s bookshelf is when it’s one of those situations where there’s just six CEO biographies and a book about the stuff they don’t teach you at Harvard Business School. But even then, to each their own, I guess.

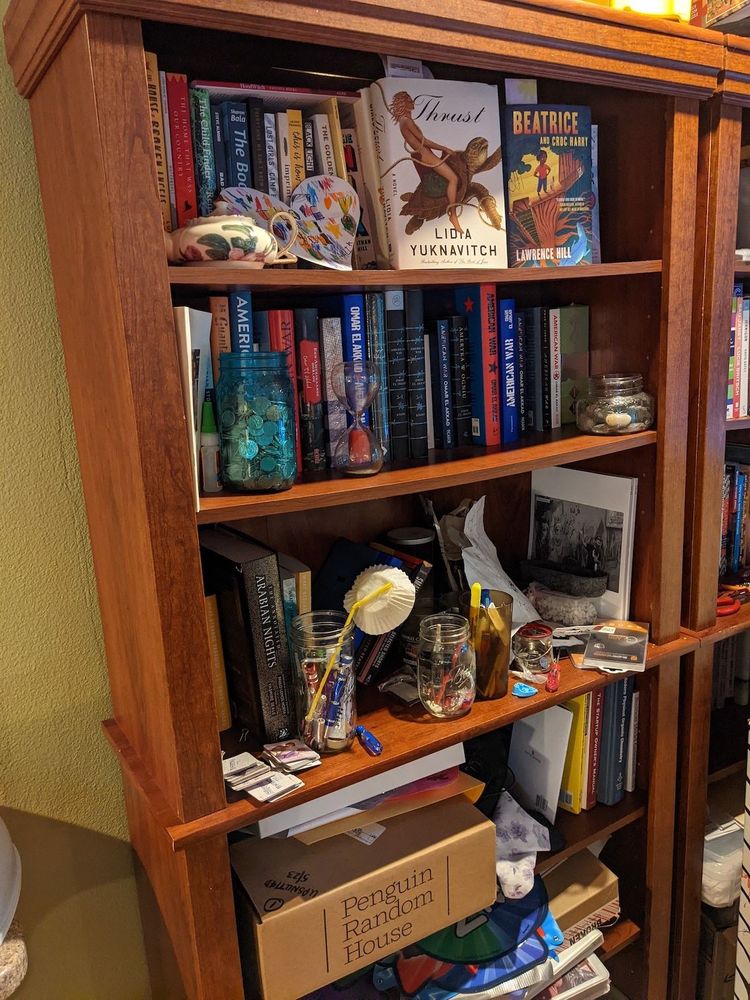

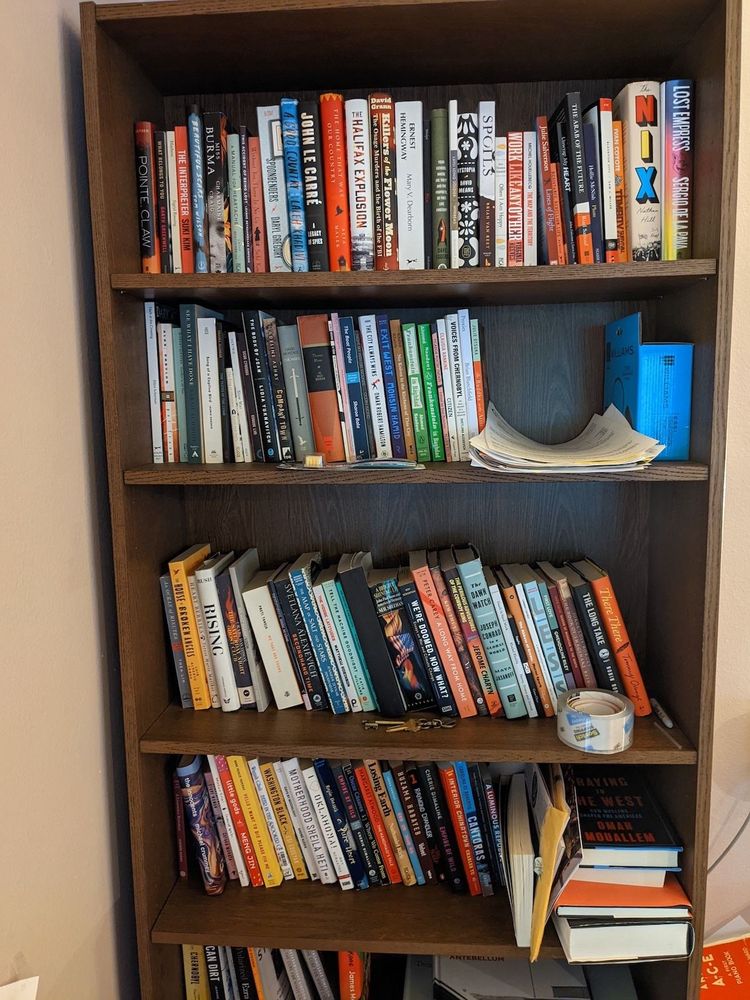

There’s a scene in the movie “High Fidelity” (I don’t remember if it’s also in the book), where Rob Gordon describes his latest rearrangement of records as not alphabetical or stylistic or by genre, but rather autobiographical. I think, more than anything else in the loose chaotic arrangement of our home life, my bookshelves are ordered autobiographically. There’s one stack of shelves in our dining room where I once tried to order each shelf simply by year—the books I read in 2017, below that the ones I read in 2018, and so on—but even that basic arrangement has been corrupted over the years. If I want to find Voices From Cheyrnobyl by Svetlana Alexievich, for example, I have to remember that I read it toward the beginning of the year, but then pulled it out at the end of the following year to reference it as the only piece of non-fiction in an article I wrote about contemporary dystopias. On another shelf I tried to keep a row of “classics,” but eventually got around to reading one of those books and disliking it so much that I moved it to what is now a one-book shelf of contrarians. Elsewhere, I reserve a couple of shelfs for my own books, the novels I’ve written and anthologies to which I contributed. These might be the most rationally ordered shelves in the house, as I don’t take my books out too often. But even these are incomplete—the two most important members of that collection, the first copies I ever received of my first two novels, sit on a separate shelf.

Overlayed onto all of this, of course, is the tyranny of children. There’s not a single bookshelf in the house that carries only books. The shelves that hold my novels, for example, are also littered with playdough molds, little inkpads from a number stamping set, toy racecars and a ceramic turtle whose origin escapes me. Copies of Green Eggs and Ham and The Book With No Pictures sit alongside Toni Morrison and Naguib Mahfouz, so intertwined the relationship that, a few days ago, when my five-year-old daughter went to pick a book for bedtime, she settled on a collection of Jorge Louis Borges short stories because she liked the butterflies on the cover. We have, since then, been spending our nights reading The Book of Sand and Shakespeare’s Memory. She’s getting really into it.

I know some people find this sort of thing deeply upsetting, but I enjoy damaging books. Not so much intentionally, but rather that passive violence that comes with the act of actually picking up and reading a book—dog-ears, coffee stains, acts of underlining so fervent they cut through the page. There’s lots of that on our shelves, in part because I do a lot of my book-buying at second-hand stores (there’s a place in Portland called Title Wave that is the bookselling arm of the Multnomah County library system. It’s a store arranged like a library, but everything on the shelves is for sale. You can get a haul for just a few bucks). There’s also the small matter of the kids getting at the books themselves, and leaving their mark. Once I explained to my daughter that signed books are generally considered more valuable. So of course she went and signed some.

Near the edge of the woods, there’s a little one-bedroom unit that I use as my writing studio. Mostly, this is my space alone, and here the books are given even more free reign than in the house proper. I arrange them in towers on the floor, up on the counters, the couch. Near the computer, I keep a very short stack of emergency reads—stuff I’ve been asked to blurb for which the deadline is nearing or already passed, the newest works of authors I’m going to be doing events with, books I really need to get through for work. Otherwise, again, it’s largely autobiographical. If I want to re-read Frank: Sonnets, I have to remember that I returned from a writing retreat and immediately stacked it atop my tower of favorite reads of the year, but later rearranged it after my daughter came down to the writing studio and, having declared the floor lava, demanded I build her a path to get from one end of the room to the other.

One day, maybe, I’ll win. Years will pass and the kids will leave the house and you’ll come visit and you’ll find everything in its right place. No more playdough molds or turtles of uncertain providence. No more glitter-bombed first editions, only serious and efficient ordering of books (of which, if I continue buying and being sent them at the current pace, there will be thousands and thousands). I’m not looking forward to it. When we read, as when we write, we are doing the work of aliveness, which is separate from and of vastly higher order than simply living. Aliveness is messy, irrational, a rat’s nest of whims and wants, triumphs of bad sense and failures of composure. I like my messy home life of books. I don’t want order.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

El Akkad, Omar. “Shelf Portrait: Omar El Akkad.” Shelf Portraits, 24 February, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-omar-el-akkad. Accessed 15 February, 2026.

APA

El Akkad, Omar. (2023, February 24). Shelf Portrait: Omar El Akkad. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-omar-el-akkad

Chicago

El Akkad, O. “Shelf Portrait: Omar El Akkad.” Shelf Portraits, 24 February, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-omar-el-akkad.

Omar El Akkad

Omar El Akkad is an author and journalist. He was born in Egypt, grew up in Qatar, moved to Canada as a teenager and now lives in the United States. The start of his journalism career coincided with the start of the war on terror, and over the following decade he reported from Afghanistan, Guantanamo Bay and many other locations around the world. His work earned a National Newspaper Award for Investigative Journalism and the Goff Penny Award for young journalists. His fiction and non-fiction writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, Guernica, GQ and many other newspapers and magazines. His debut novel, American War, is an international bestseller and has been translated into thirteen languages. It won the Pacific Northwest Booksellers’ Award, the Oregon Book Award for fiction, the Kobo Emerging Writer Prize and has been nominated for more than ten other awards. It was listed as one of the best books of the year by The New York Times, Washington Post, GQ, NPR, Esquire and was selected by the BBC as one of 100 novels that changed our world. His new novel, What Strange Paradise, was released in July, 2021 and won the Giller Prize, the Pacific Northwest Booksellers’ Award, the Oregon Book Award for fiction, and was shortlisted for the Aspen Words Literary Prize. It was also named a best book of the year by the New York Times, the Washington Post, NPR and several other publications.