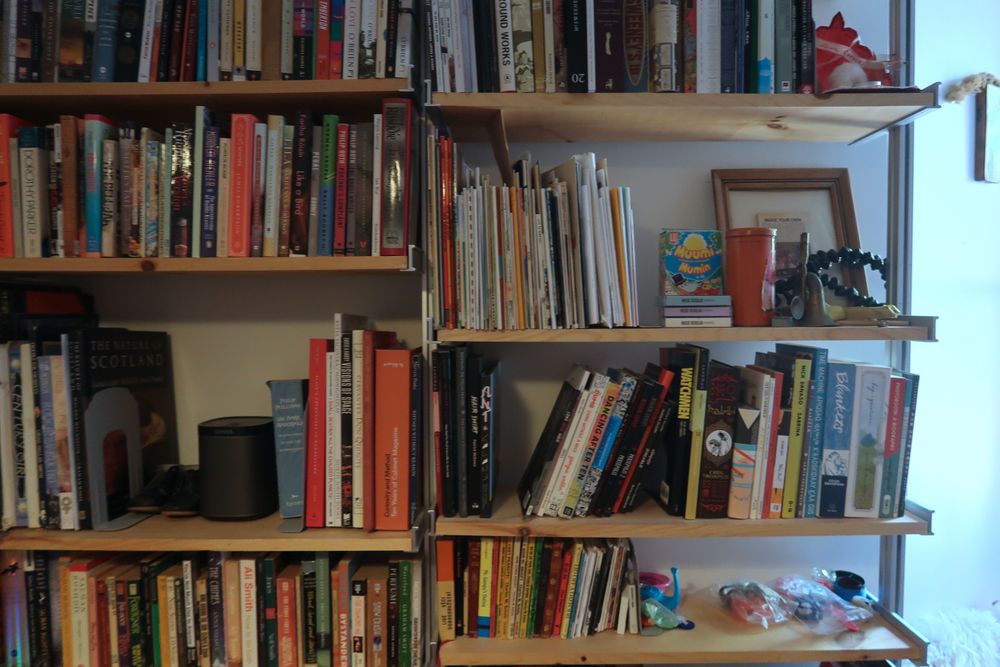

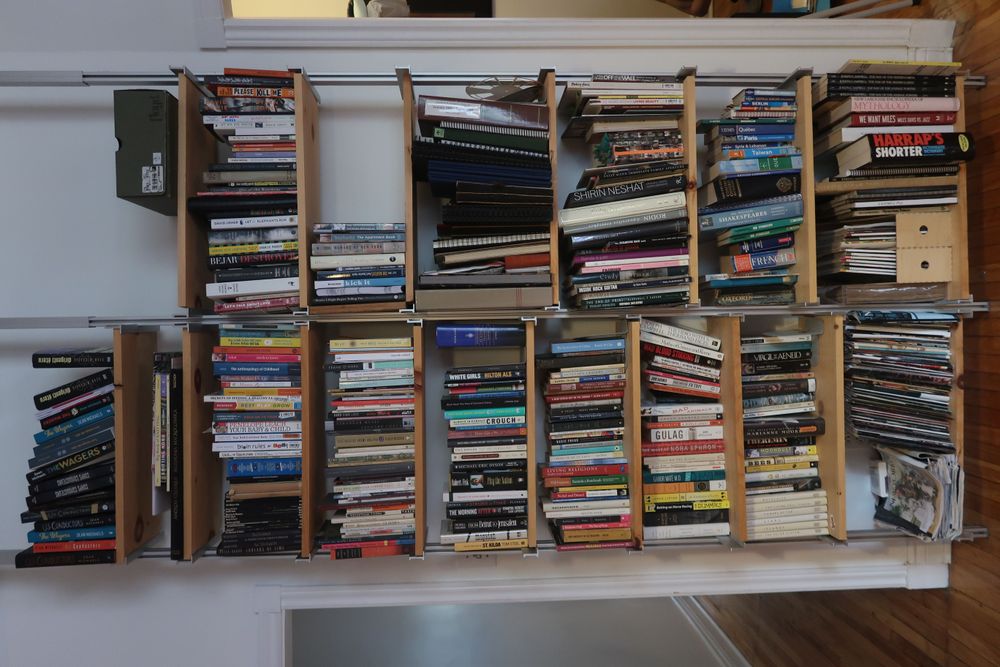

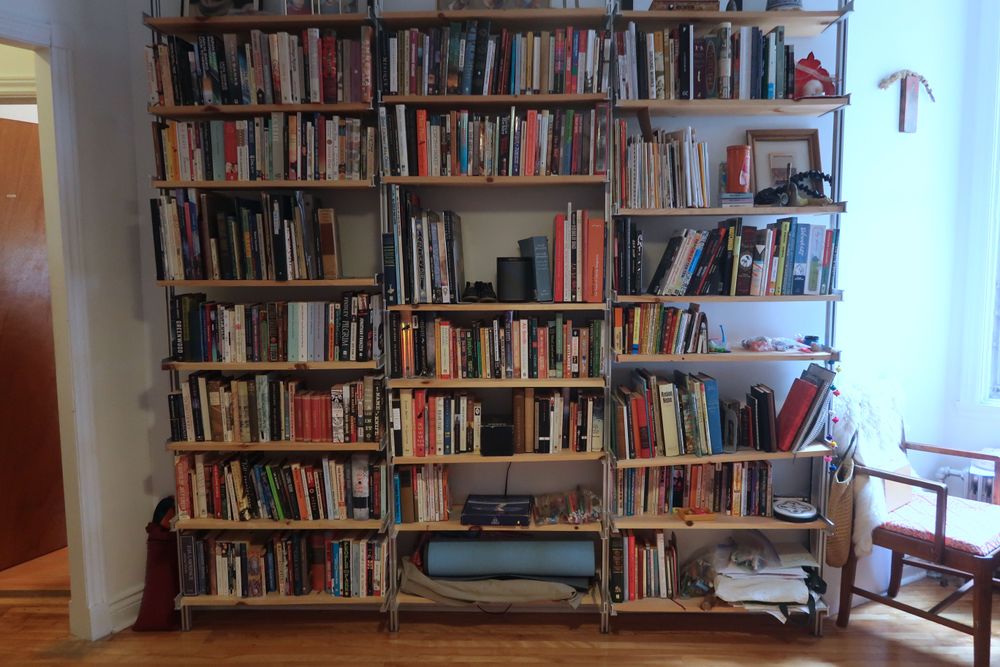

Our “library” is in the middle of our apartment. I put “library” in quotation marks because the term seems so mannered, so loaded: really I just mean a bunch of bookshelves. But it’s an awkward room in the centre of our generous (rented) apartment, a crossroads between kitchen, living-room and bedrooms, and since it isn’t useful for much else, that’s where we decided to stash our books.

There are a lot of them. More than I’d expect! I still feel a constant creeping shame that I don’t buy more books. I’m a writer—shouldn’t I be bringing home new books every week? Browsing the “new arrivals” at the used bookshop around the corner; attending readings; nourishing my mind with art-books, poetry and contemporary novels in translation? But the truth is we try to keep our expenses down, I use the library a lot, and ultimately I make my book purchases in spurts. I binge.

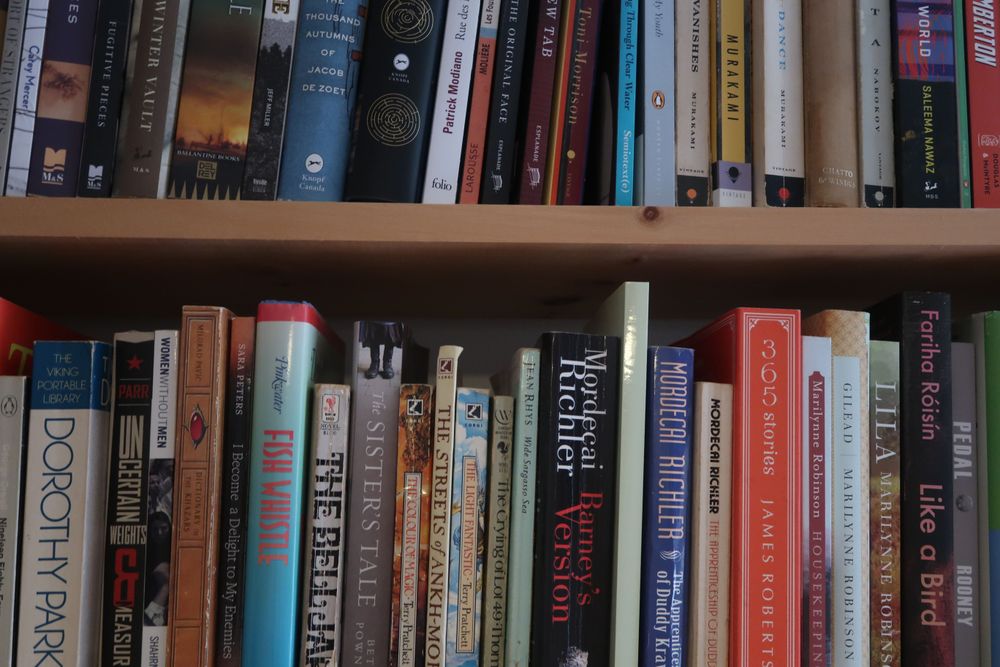

Growing up, one of my family’s most frequent excursions was to used book sales. The kind that take place in church basements and school gyms, with thousands of random volumes in hundreds of cardboard boxes. My parents’ favourites were the ones where you paid by weight, or number of boxes. My mum (who was a bookbinder) and my dad (who had an early obsession with typography) are the kinds of people who love books as objects and also books as capsules of information: there are bookshelves in nearly every room of their house, filled with books on anything they might ever want to know, from Indian cooking to English gardens to collections of essays by long-forgotten New Yorker and Punch writers. I think it is because I grew up like this, with a book on any topic just a few steps away—collections of wonder all over the damn place— that I find my home library so skeletal, despite its (completely acceptable) scale. Mostly fiction, sorted by author, as well as scrambled regions of non-fiction and comics and poetry and reference books. I rarely reread books, but I still keep them in the house: the comfort of old friends, memory and experience made literally heavy. When I moved in with my partner I insisted we “merge” our collections rather than keeping them separated: this seemed part of a (maybe co-dependent) life together. We would interweave our identities—our joys and our knowledge and our pasts, somehow, letting them live side by side.

Early in my career, I was more self-conscious about being a writer—more nervous about living up to that title. One of the places this manifested was in my home library. When people came over, I’d fear it wasn’t cool or deep or “literary” enough: whereas I was comfortable with the notion of a diverse record collection—one that comprised pasts as well as presents, and a range of commercial/uncommercial musics—I worried that a “serious” writer was only supposed to own certain kind of books. This had nothing to do with the private role of my library (that is, which books I wanted near me), but rather the public one: the fear that other people might disparage my interior world based on the books I kept on my shelves. Library as performance.

I knew the reasons I owned so much YA, commercial fantasy and sci-fi (which is to say: I understood the ways I enjoyed it); but would others think this made me frivolous, or that the “real” literature—which I read, but also wrote—was some kind of smokescreen, or fraud?

Obviously the answer is no: people don’t give a shit, especially the people I would ever invite into my home. And as I grew more confident in my identity as a writer I grew less self-conscious about what anyone would think about my books: who I am is in my work, and I don’t need to pretend anything else. But I admit that when it came time to photograph my library for this project, those old thoughts swirled up: which books should I show, which should I obscure? Which sections of my collection cast me in the best light?

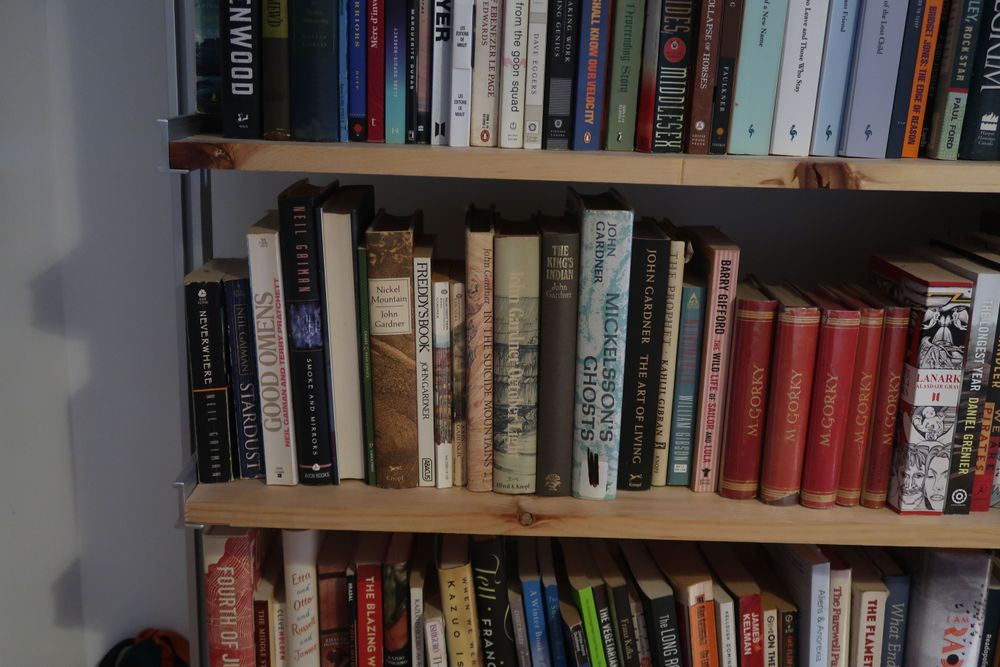

This is only even an issue because it is important to me to keep old, embarrassing books around. The books I once loved, even if I genuinely no longer do: these are souvenirs of past phases, past selves, and of journeys undertaken. Artifacts of who I no longer am feel as powerful, more powerful in many ways, than the symbols of who I am today. My Sandman books, my Robert J. Sawyer novels, the abridged Shakespeare plays I gobbled up as a teen: I like to look at a person’s library and see all the messy, varied, cheesy, tacky whole of them—of which the subtle, mature “depths” form only one part.

Some years ago, the messiness of history felt particularly relevant—and, frankly, odious—when a writer I knew was accused of some terrible behaviour. This wasn’t a friend, or even someone I really liked—but he was acclaimed and powerful and I had met him on the very first night of my very first book tour. That evening he read and I read (and a third writer read) at a festival in Ottawa, and for the first time I felt like real, live author—the kind of author who was now an author forever, irreversibly. That night felt important—it was one of those little resting-places in the journey of a life. At the end of the event, I bought a copy of this writer’s latest book. He inscribed it to me generously, welcoming me as a colleague.

I read the book shortly after; it was OK. But that object meant something more to me than the story in its pages: it was a souvenir of a moment, and felt like an emblem too—like a kind of graduation card. I put it on my shelves.

When the writer’s scandal surfaced, I didn’t think about that book. (There were other things to think about.) But one afternoon I noticed it again, innocuous on my shelves, and I literally gasped. It meant something different now. What should I do with it? Throw it out? Probably. I felt a strong reflex to do this—to toss it in the garbage can (not even the recycling bin) and pretend it was never there. I didn’t want this man or his book in my house. More than that, I realized, I didn’t want anyone to see it in my house.

But that performative impulse brought me up short. I distrust it these days—the fear of other people’s judgment. Other things are more important—like kindness, and integrity, and vulnerability. And the truth was: I owned that book. I crossed paths with that man. My own life, my own writing career, had been touched by him—maybe it had even benefited in some minuscule way. The artifact hadn’t lost its original meaning—but it had a shadow upon it, inside it—the kind of shadow I am now too familiar with, as I reckon with my various complicities. In a way I didn’t feel I had a right to throw this book away—to pretend it had never happened. At the same time, I didn’t want anyone (even myself) to believe that I was honouring this man, with his book in my house. So what I did, in the end, was to turn it around: to hide its spine and the name written there. Sufficient? Insufficient? I have no idea. I don’t have to decide forever; I can throw it out next week. But for now I keep it there: an ugly reminder of who I am, where I’ve been, and how close I have been to wickedness.

Gallery

How-to-Cite

MLA

Michaels, Sean. “Shelf Portrait: Sean Michaels.” Shelf Portraits, 14 April, 2023, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-sean-michaels. Accessed 14 March, 2026.

APA

Michaels, Sean. (2023, April 14). Shelf Portrait: Sean Michaels. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-sean-michaels

Chicago

Michaels, S. “Shelf Portrait: Sean Michaels.” Shelf Portraits, 14 April, 2023, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/shelf-portrait-sean-michaels.

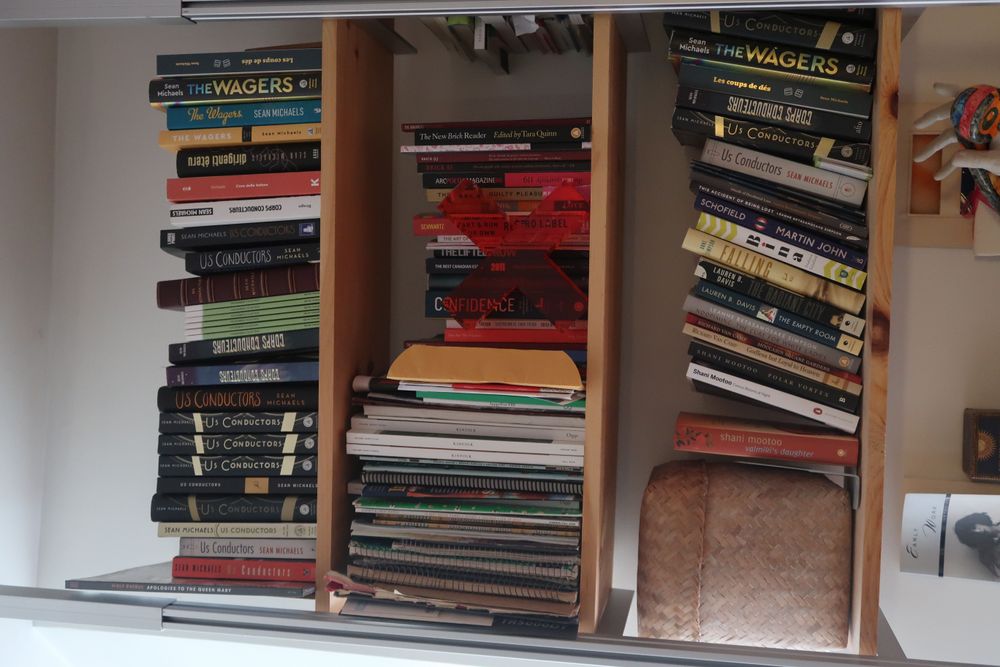

Sean Michaels

Sean Michaels is the author of the novels Us Conductors and The Wagers, and his non-fiction has appeared in The Globe & Mail, The Guardian, Pitchfork and The New Yorker. He is a recipient of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the QWF Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize and the Prix Nouvelles Écritures, and he founded the pioneering music blog Said the Gramophone in 2003. His third novel, Do You Remember Being Born?, will appear in September 2023. Born in Stirling, Scotland, Sean lives in Montreal.

Author photo by Julie Artacho.