How does a Cree/Michif-speaking Métis with an orally-based land culture begin the road to becoming a professor; a profession that, in large measure, is all about amassing books and filling one’s life with the written and urban culture of colonial education? A more concrete way of putting this, and in terms of experience, is to say that my early childhood years were filled with the comical and yet complex Wehsakehcha (the Cree legendary figure also known as “trickster”) and my school years were full of white-invented savages, settlers and “Shakespeare” (among the numerous fictional and non-fictional readings public schools offered). For me those years were both easy transition and difficult dissonance.

I started this transition from orality to English literacy a long time ago; perhaps it began at age 4 or 5, the moment in which I opened Cowboys and Indians comic books such as Billy the Kid, Davey Crocket, The Lone Ranger and Tonto, and so forth. Or when I first saw pictures of Dick and Jane, Sally, Spot and Puff in my older brother’s Red, Yellow and Blue readers.

These sources did two things to me: one, I wanted desperately to learn how to read; and two, I became unconsciously more alienated from my childhood upbringing. I wanted to learn how to read for a very practical reason – I wanted to know what the little alphabets inside the cloud over each character’s head were saying. In part, comic books spurred my thirst for literacy, and for a long time I thought literacy was the best thing ever invented. I thought so without realizing for many years that learning to read carried a cultural price. Without my knowing these readings were the beginnings of my Otherness. My intellectual exile in my own homeland. The dissonance between Wehsakehcha and Cowboys and Indians. In short, Wehsakehcha brought me laughter and wonder; Cowboys and Indians comics (and movies) caused me discomfort, confusion and racial shame. Wehsakehcha is ultimately about being human; Cowboys were all about dehumanizing and killing “Indians.” But all this is a big story that requires more space than I can give it here, and one that is relayed in a number of my writings (When the Other Is Me, for instance).[1]

The other “big story” about my journey from orality to literacy is actually more complex than just moving from a culture of words to a culture of writing. And that is difficult enough. What is not well known is that Métis Nation people can claim a rich literary heritage from both First Nation and Euro-Canadian peoples. They have inherited, as I have said elsewhere, “a wealth of literatures – literatures spoken, sung, performed, painted, carved, engraved, pictographed, penned and stereo/typed (pun intended). And now cybered.[2] In addition to this heritage, the Métis of Rupert’s Land, along with other Native people, were involved in the development of the Cree syllabary in the 1840s. Syllabic literacy spread among Native peoples throughout the plains and the north. Right up to the 1970s my mother and her sisters were literate women who wrote to each other in the syllabic system. My mother used to read the Roman Catholic Bible and other religious material in syllabics. In effect, I grew up in literacy. And in orality. Perhaps this is why learning the English alphabet and phonetic system came so easy for me. And actually, I learned how to read before I entered grade one, and once in school, I loved reading and spelling the most.

I still love words. Whether Cree, Michif, English or the little of French I learned in high school. And this love began by listening to my mother and sometimes grandmother tell us Cree legends and myths in Cree. Or my mother reading to us from her syllabic Bible and pamphlets, or letters from her sisters. Both my grandmother and mother were fantastic storytellers; they did not just tell stories, they virtually performed them in their animated ways of speaking. Their ways of telling stories transported us to worlds and characters that were magical and transcendent.

I loved pictures too. Some comic books were also magical and transcendent, not only because of their storylines but because of the visual art that inspired imagination. Like a giant yellow moon against a navy blue starry sky, moon reflected off a perfectly still river which carried a man in a birchbark canoe. Like in The Book of Hiawatha. Or the giant yellow moon that lit the way in the dark for The Singing Donkey and his menagerie of fellow-abandoned friends in search of a home.

There is considerable universality to stories whether told or written. In Coyote and the Roadrunner, for example, Coyote’s attempts to trick Roadrunner which always backfired on him reminded me of Wehsakehcha’s antics. Like Coyote, Wehsakehcha was often wiley, scheming and over-confident, if not a downright braggart! Yet his schemes to outwit others often failed and we could laugh with him, knowing intuitively that we all have tricksterisms in us. And so it is with Coyote. Stories can be a bridge between cultures – in an unexpected way, Wehsakehcha and comics provided that bridge for me. I have retained my orality and at the same time my youthful encounters with comics turned into my love of books.

Today I have more books than I know what to do with! Books on nearly everything and of course, loads related to my work and area of specialization. Do I have any special attachment to any particular books? I would have to say dictionaries. I have a lot of dictionaries and thesauruses. English, after all, is my second language and I have had to look up a lot of words – a necessity I enjoyed early in high school. Indeed, as a graduate student I often carried a dictionary right into my university classes. In the field that I teach, Native Studies, some students, Native and non-Native alike, have difficulties writing essays. Part of that has to do with lack of timely research but it also has to do with lack of facility with the English language. Students often seem surprised when I tell them that English is my second language and that it is the humble (and oft neglected) dictionary that has enabled me to deepen my knowledge of English. And these days one does not even have to go to a library for a dictionary – they just have to go to their smart phones! Still, learning a second language is really a lifelong challenge.

I never kept my comic books but I have never forgotten them – both the few beautiful ones, and the all too numerous racist ones. Neither have I forgotten Wehsakehcha. Yes, I have more books than I have shelf space. In fact, my mother, a fastidious and organized woman, would be horrified at how untidy my book stacks are – but I know she would be most happy that I still speak Cree and laugh with Wehsakehcha quite often.

Gallery

References

LaRocque, Emma. When the Other Is Me: Native Resistance Discourse, 1850-1990. University of Manitoba Press, 2010.

----. “Contemporary Metis Literature: Resistance, Roots, Innovation.” The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature, edited by Cynthia Sugars. Oxford University Press, 2016.

How-to-Cite

MLA

LaRocque, Emma. “Wehsakehcha, Comics, Shakespeare and the Dictionary.” Shelf Portraits, 25 June, 2021, richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/wehsakehcha-comics-shakespeare-and-the-dictionary. Accessed 23 June, 2025.

APA

LaRocque, Emma. (2021, June 25). Wehsakehcha, Comics, Shakespeare and the Dictionary. Shelf Portraits. https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/wehsakehcha-comics-shakespeare-and-the-dictionary

Chicago

LaRocque, E. “Wehsakehcha, Comics, Shakespeare and the Dictionary.” Shelf Portraits, 25 June, 2021, https://richlerlibrary.ca//shelf-portraits/wehsakehcha-comics-shakespeare-and-the-dictionary.

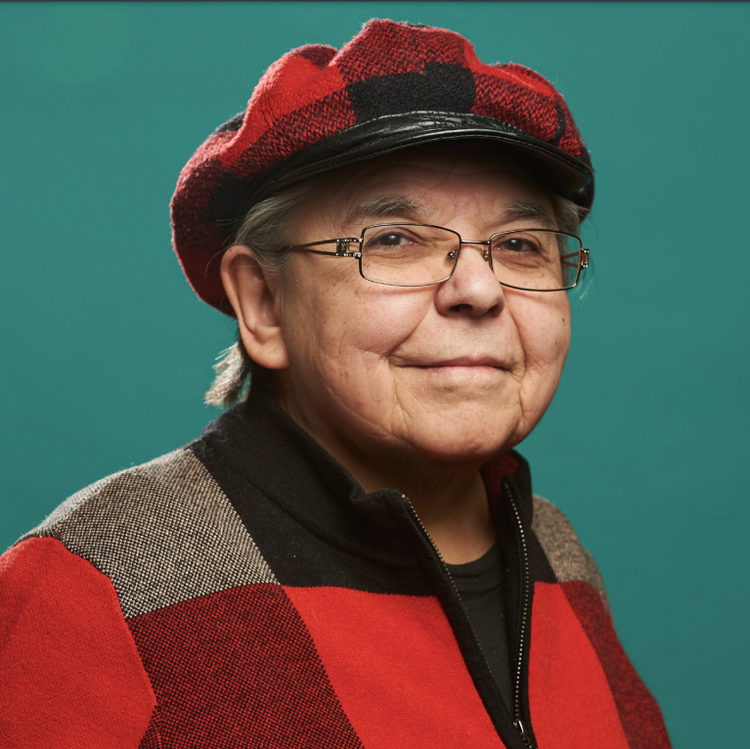

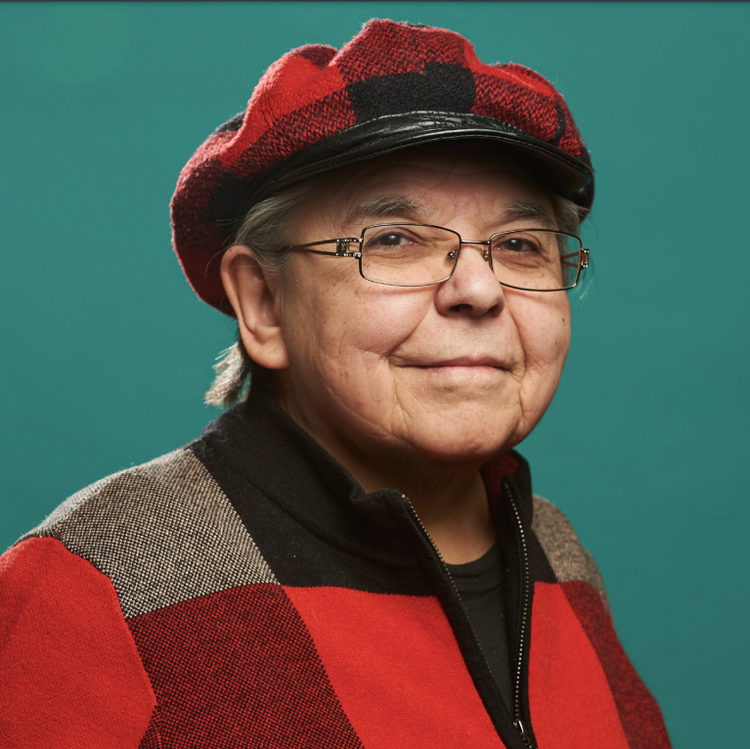

Emma LaRocque

Dr. Emma LaRocque is a scholar, author, poet and a veteran professor in the Department of Native Studies, University of Manitoba. Her prolific career includes numerous publications in areas of colonization/decolonization, Canadian historiography, racism, violence against women, and First Nation and Métis literatures and identities. Her poems are widely anthologized in prestigious collections and journals. She is frequently cited in a wide variety of venues and has lectured locally, nationally and internationally on Re-settler/Indigenous, or colonizer/colonized relations.

Overcoming obstacles of marginalization and poverty LaRocque acquired a Bachelor of Arts (1973) degree in English/Communications from Goshen College, Indiana; a Master of Arts (1976) in Peace Studies from the Associated Mennonite Seminaries, Elkhart Indiana (for which she received a Rockefeller Fellowship), and an MA in History (1980) as well as a doctorate in Interdisciplinary Studies in History/English (1999) from the University of Manitoba. Her dissertation on Aboriginal resistance literature (1999) was nominated for the Distinguished Dissertation Award, University of Manitoba.

A role model for Indigenous scholars and students, Dr. LaRocque has been a significant, if not leading figure, in the growth and development of Native Studies as a teaching discipline and an intellectual field of study. Her work has focussed on the deconstruction of colonial misrepresentation and on the advancement of an Indigenous-based critical resistance theory in scholarship, and is one of the most recognized and respected Native Studies scholars today.

In 2005 Dr. LaRocque received the National Aboriginal Achievement Award. In 2019 she received the Indigenous Excellence-Trailblazer Award from the University of Manitoba. She is author of Defeathering The Indian (1975), which is about stereotypes in the school system; and more recently, author of When the Other Is Me: Native Resistance Discourse 1850 - 1990 (2010), which won the Alexander Kennedy Isbister Award for Non-Fiction.

LaRocque is originally from a Cree-speaking and land-based Métis family and community from northeastern Alberta.