Richler, the Novelist, and His Oral Fixation

Alisha Dukelow

About Exhibit

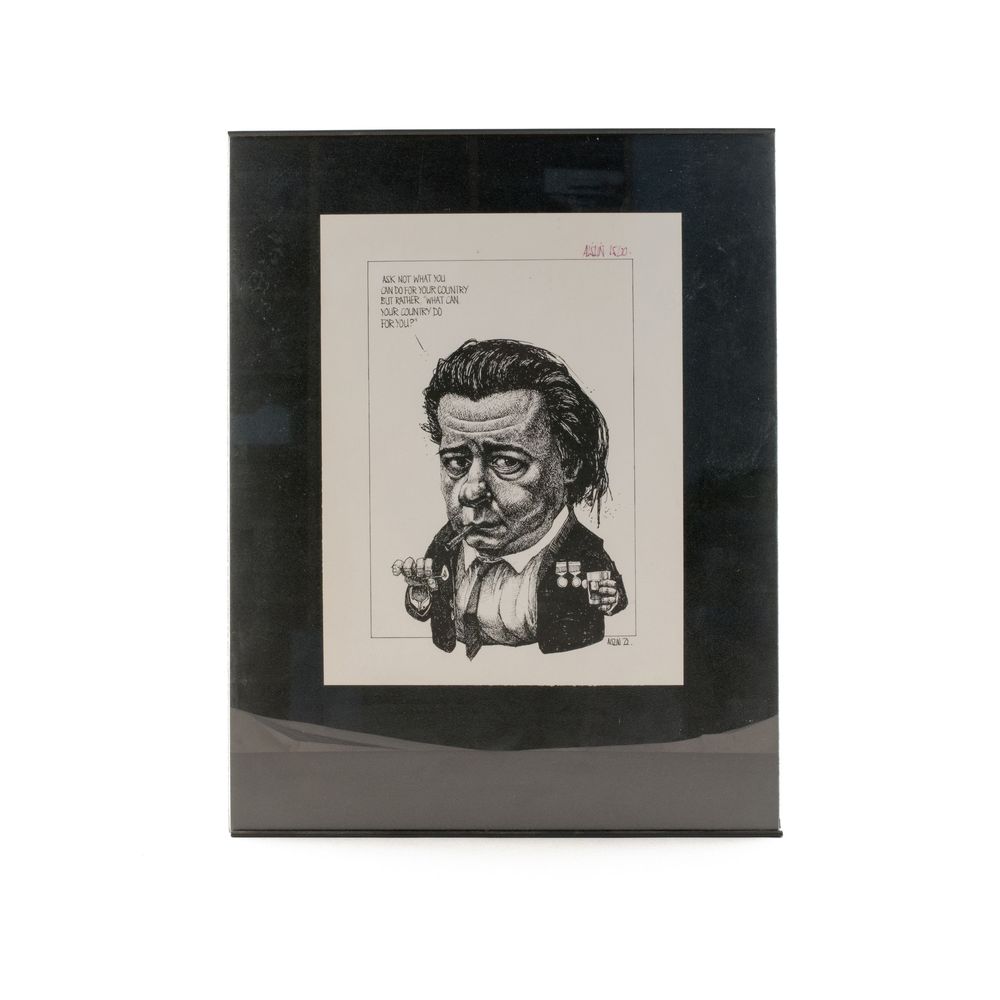

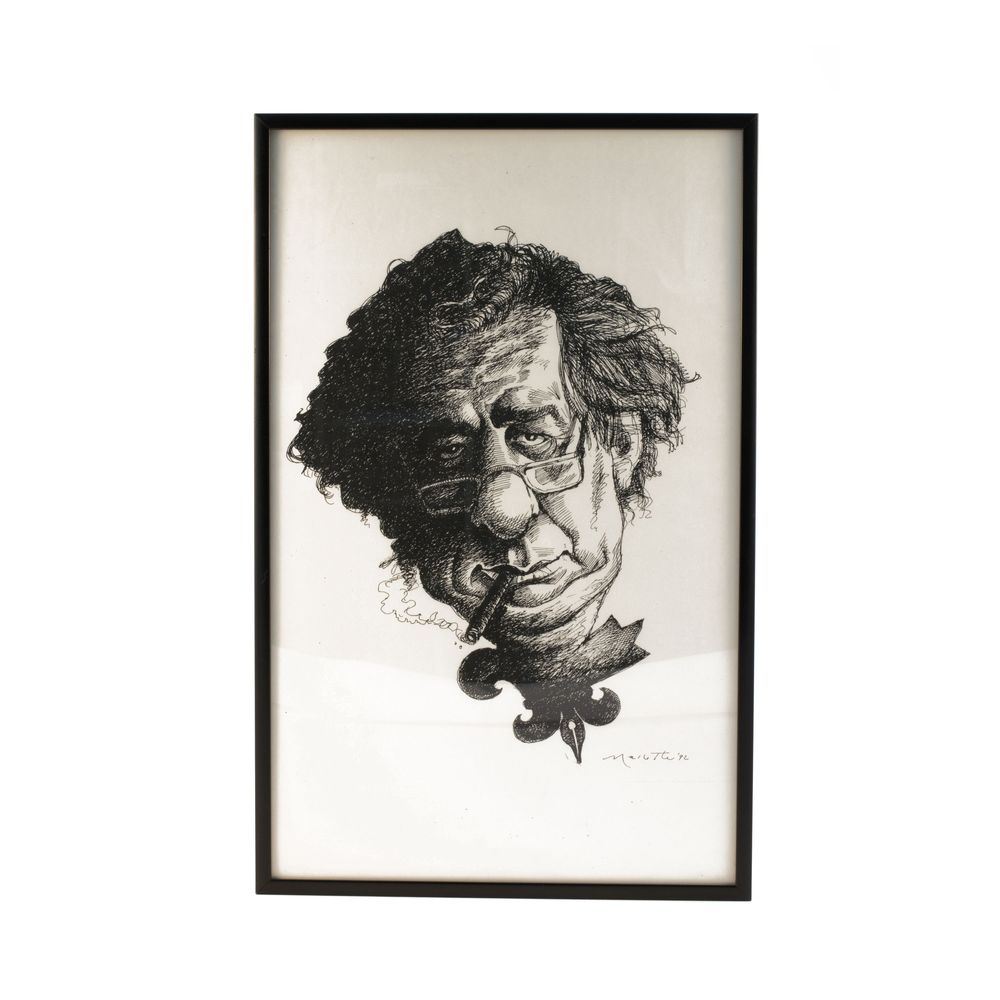

In cartoon drawings and photographs, Mordecai Richler is typically imaged with a cigar, and often, with a glass of whiskey: the acerbic, satirical novelist favoured a Schimmelpenninck, if not a Montecristo no. 4 or Romeo y Julieta, and a Scotch or single malt [1]. Noah Richler remembers his father “smoking Dutch cigarillos at his desk until the large ashtray was filled with their broken ends,” and attests that, after Mordecai’s second bout of kidney cancer, “it did not take long before [he] found him on the patio of [their] house on Lake Memphremagog, not yet ten in the morning, having a cigar with his black coffee” (“My Dad, the Movie, and Me”). Documentation of Richler’s tobacco and alcohol consumption melds with evidence of his writing habit; the fact that he was a lifelong smoker, especially, permeates our recollection of his material practice. But why has the masculine, chain-smoking and hard-liquoring writer (of which Richler is an example) cemented as a canonical or caricatured portrait in Western and European culture? Can the act of lighting a cigar, inhaling, and exhaling, or sipping a whiskey, neuronally stimulate a novelistic methodology? Could the intoxicating repetition of such acts trigger a characterizing detail, line of dialogue, or metaphor [2-4]? Additionally, Richler’s famous enjoyment of Schwartz’s smoked meat, the “Wilensky’s Special” sandwich, St-Viateur bagels, and chopped liver with onions, locationally and culturally tags and sensorially textures his authorial aura and work [4]. How did Richler’s oral fixations—his smoking, drinking, and eating rhythms—inform the chronotopes of his novels? This display and essay probes and imagines the psychological link between oral fixation in Richler’s fictional and autobiographical worlds and creative process.

The psychoanalytic point of view would certainly underline that Richler had a troubled dynamic with his estranged mother, Lily Rosenberg, and indeed, Richler invested, at least playfully, in Freudian tropes. On his shelf are numerous books by and about psychoanalysis’ patriarch, including: Sigmund Freud: His Life in Pictures and Words; Freud and Jung: Years of Friendship, Years of Loss; Freud and His Father; In the Freud Archives; Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend; Freud: A Life for Our Time; and The Problem of Lay Analyses. Also well-read is Richler’s copy of the DSM-IV and its criteria for both tobacco and alcohol “Use Disorder” and “Withdrawal” [5]. Furthermore, his male protagonists have conflicted relationships with their mothers—if their relationships exceed repressed backstory or subtext—and are characterized by their oral-receptive and/or oral-aggressive personalities as they smoke, drink, eat, and verbalize in comic excess and/or sardonic bite. For example, in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, the nervous, garrulous Duddy redundantly asks his father if his mother (who died when he was young) liked him (218), and, as his Aunt Ida presumes, his romantic relationship with Yvette is Oedipally toned (280). After Duddy loses the heavily liquored, rigged roulette game, vomits, and swallows “three hot dogs and two orders of chips” (99), Yvette lays him to rest and remarks that it is “nice to see [him] lie still for once” (100). In this moment, the infantilized, motherless Duddy, “flattered to discover that anyone [cares] enough to watch him so closely” (100), reaches for Yvette’s maternalized breast and “[fondles it] tentatively” (100) before Richler zooms in on Duddy’s mouth and the couple’s kiss. Moreover, Erna Paris refers to Joshua Then and Now as “round 3 in Richler’s battle with [Lily], following on her unflattering portrait in St. Urbain’s Horsemen” (Kramer 273). In the novel, Joshua’s negligent mother, Esther, an exotic dancer, strip teases at his bar mitzvah and cheats on his father. As Reinhold Kramer notes: “Taken generously, Esther is a witty take on Lily’s job at the Esquire Show Bar [. . .] Taken less generously, Esther is a satiric take on Lily’s coitus with Julius Frankel [with whom she had an affair], reluctantly witnessed in the next bed by the thirteen-year-old Mordecai” (274).

Less automatic a connection than that of Richler’s autobiographical and fictional backstories and their influence on depictions of his oral fixation, though, is in the way that Richler’s and his characters’ mouth-oriented objects symbolically configure novelistic superstructures of time and spacial imagery. As aforementioned, we can deduce that Richler’s protagonists’ familial histories fuel their compulsions to light up or reach for a drink; therefore, smoking and drinking, as repetitive or addictive gestures, reify the past’s intrusion on the fictive present and act against linear temporality. Then, both the snorkelling mask (a breathing device when paired with a snorkel) and the black bird whistles (which we can sonically and visually conceive, if we would like, Richler blowing through) can be linked to major images—that operate as temporal markers—in Barney’s Version and Solomon Gursky Was Here. In the former novel, a retrospective narrative, Barney’s confused, aged psyche is haunted by flashbacks of his last encounter with Boogie, who he is mistakenly accused of murdering. After Boogie sleeps with Barney’s wife, Barney pleads with him, via gunpoint, to be a co-respondent in his divorce, and Boogie, rather than agree, decides to go snorkelling. Boogie effectively replaces his cigar and quells his slurred banter with Barney’s snorkel before he disappears into the psychic murk of Lake Memphremagog, and Barney struggles to remember and re-remember the scene:

I scooped up the gun and aimed it at him. “Will you testify?” I demanded.

“I’ll think it over on my swim,” he said, rising shakily to fetch my snorkelling equipment and flippers. “You’re too drunk to swim, you damn fool,” I said, following after him with that revolver still in hand. “You come too,” he said, starting down the steep grassy slope to the water. “It will do us both good. Ime-tay or-fay old oys-bay to et-gay ober-say.” [. . .] “Stop,” I hollered, “or I’ll shoot.” Boogie guffawed in appreciation of my jest. He paused to adjust his snorkelling gear, falling down twice [. . .] Then he zigzagged the rest of the way down the slope, raced across the dock, and plunged into the lake, disappearing underwater. (296-297) [6]

Comparably, through the alcoholic lens of Moses Berger, Solomon Gursky Was Here crookedly draws the bootlegging Gursky family’s expansive, achronological timeline. The timeline mazes from early Arctic explorations, to Mao’s Long March, to the Watergate scandal, Operation Thunderbolt, and the Franklin Expedition, and is dotted and bookended with the sonic visual of the black raven. The raven swoops in as a totemic response when the “inhuman call” is made: “some sort of sad clacking noise, at once abandoned yet charged with hope, coming from the back of [the] throat” (3). Arguably, the raven stands for the missing Solomon, reincarnated, and simultaneously, it is omnipotently and imaginatively seductive and minacious. When Moses inspects the painting of the raven plucking at a human head, Sir Hyman recounts the related Inuit legend:

Once, a raven swooped low over a cluster of igloos and told the people that visitors were on the way. If the people did not encounter the travellers before nightfall, he said, they were to make a camp at the foot of the cliff. The visitors did not turn up and the people built new shelters at the foot of the cliff, as instructed. When the last stone lamp in the igloos was put out, the deceitful raven flew straight to the top of the cliff that loomed over the igloos. On the summit, perched on an enormous overhang of snow, he began to jump, run, and dance, starting an avalanche. The trusting inhabitants below were buried, never to waken again [. . .] the raven did not lack for tasty provisions well into summer. (191)

The novel ends with its initial chronotopical focus on the sky above Lake Memphremagog:

Watching the Gypsy Moth climb, Moses believed that he saw it turn into a big menacing black bird, the likes of which hadn’t been seen [. . .] since the record cold spell of 1851. A raven with flapping wings. A raven with an unquenchable itch to meddle and provoke things, to play tricks on the world and its creatures. (558) [7]

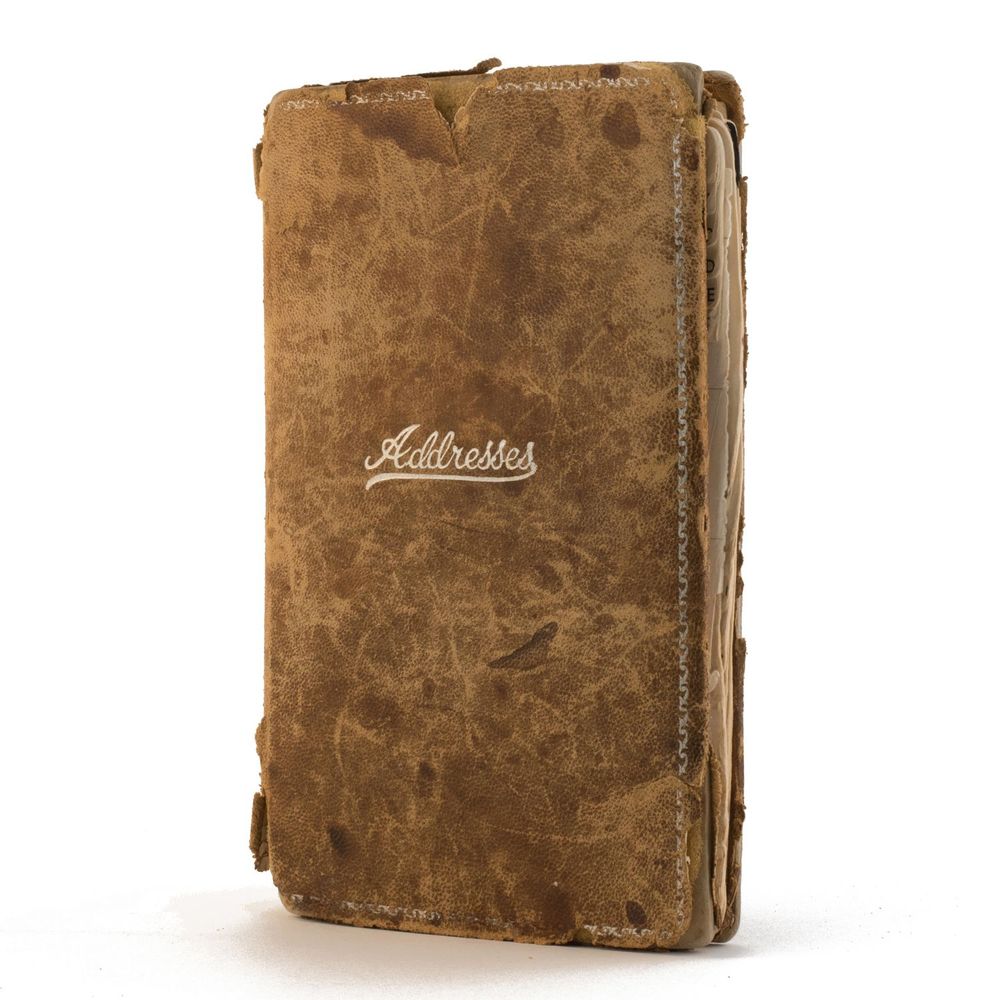

Can the symbolic insertion of Solomon Gursky’s raven—which explodes Richler’s normally human, satirical-realist bounds—be traced back to the display’s bird whistles, or vice versa? Through the orally significant objects of the snorkelling mask and whistles, we can envisage the broader psychological elements of Richler’s scenery: subconscious, from mask to water, and creative, from bird to high air. The smoking and drinking paraphernalia that Richler left behind cues us as to where he and his characters have been in their personal, familial, discords and histories, and where they have been more concretely, too: we know that his leather cigar case is from somewhere in Spain; his VAT 69 Scotch glass, from Diageo, a British alcoholic beverages company with headquarters in London; his matchbook, from Le Taj restaurant. Finally, the travelling toothbrush that Richler kept but never used, punctuates the collection as an example of one of the orally fixated objects that imbued, permitted, and made possible Richler’s fluid, psychic, spatiotemporal travelling experiences: with each object, prompting us towards a locale of the novelist’s mind [8].

Gallery

More Exhibits

The Author as Collector

Jennifer Breaux, Jason Camlot, Alisha Dukelow, Sean Gallagher, Kaitlynn McCuaig, Chalsley Taylor

From the Desk of Mordecai Richler

Jason Camlot

Oh Richler! Oh Quebec!

Jennifer Breaux

Richler’s Quebec

Sean Gallagher

Richler’s Northern Canada

Kaitlynn McCuaig

The Generic Trials of Duddy, Adapted

Chalsley Taylor